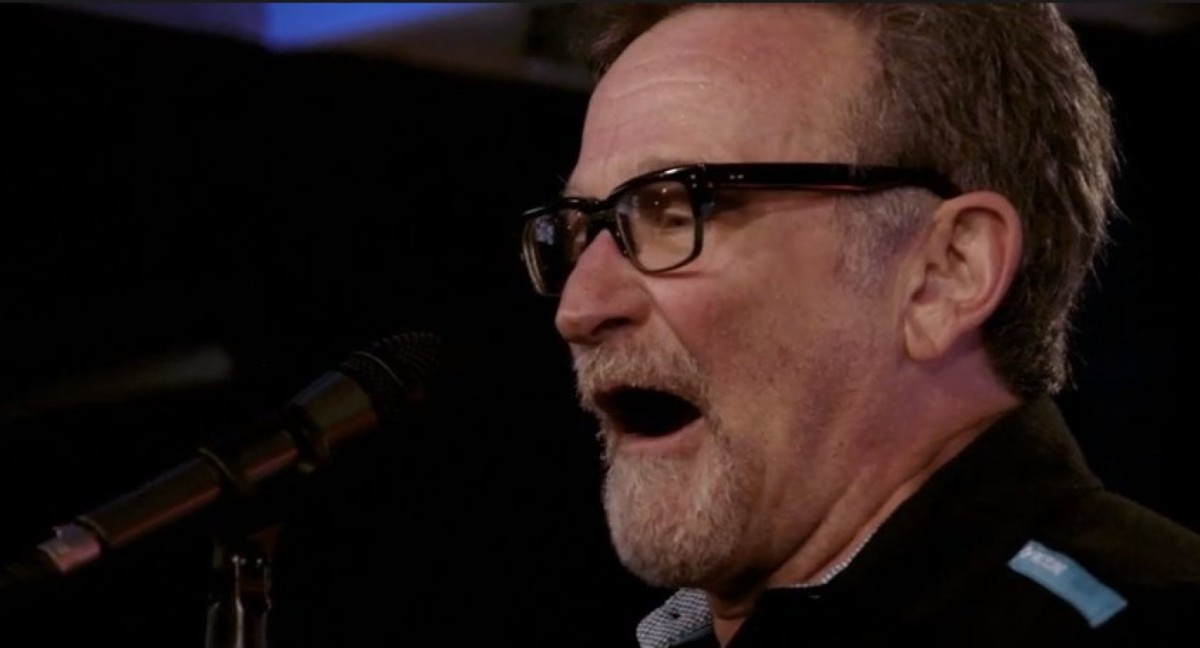

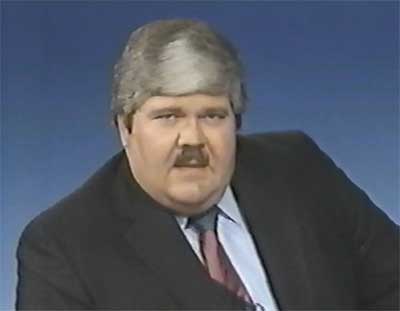

Locus Magazine reports the sad news that George Scithers, who was a founding editor of Asimov’s, an editor of Amazing Stories, and who revived Weird Tales in 1987, serving as its editor through 2007, passed away on April 19, 2010 of a heart attack.

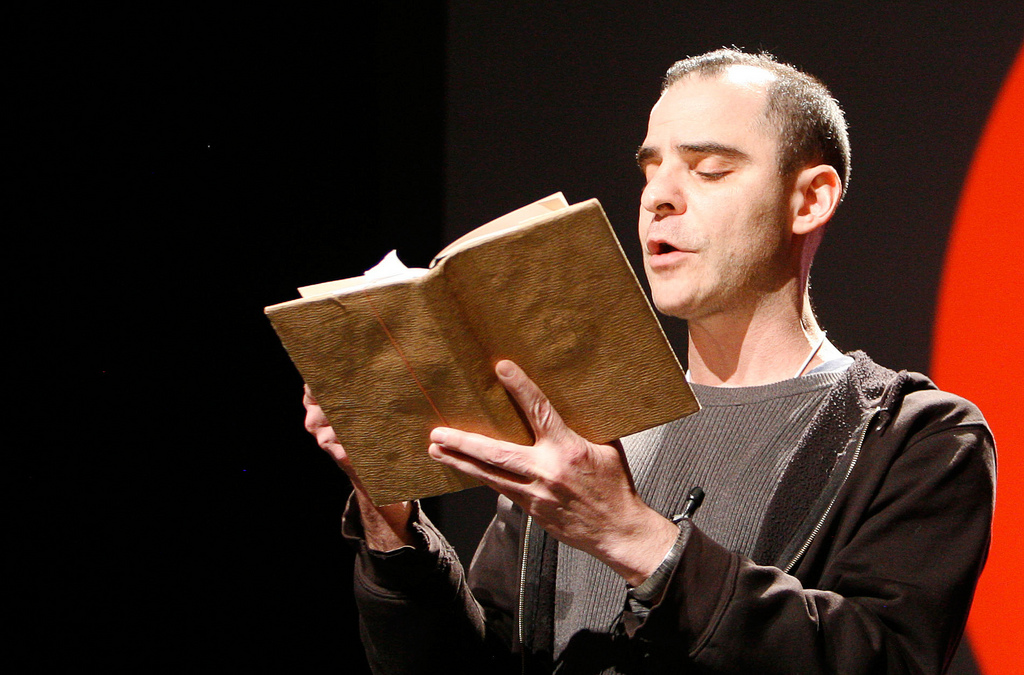

I ran into George at BEA in 2006, and conducted an impromptu interview for The Bat Segundo Show. Our conversation is transcribed below. This was still in the “wet behind the ears” stage of the program. In the transcript, I have spared people the dreaded you knows and likes that were then quite frequent. But I hope that the interview sufficiently captures George’s spirit. In my admittedly brief conversation, I found George to be a very friendly and encouraging man. (You can also listen to the conversation in the audio file attached to the end of this post. Or, if you prefer, you can listen to the entire show here.)

Correspondent: So I’m here with George Scithers of Wildside Press. He is also the man who revived Weird Tales Magazine. Maybe you can tell us about that and what’s coming up from Wildside.

Correspondent: So I’m here with George Scithers of Wildside Press. He is also the man who revived Weird Tales Magazine. Maybe you can tell us about that and what’s coming up from Wildside.

Scithers: Oh, almost fifteen years ago, John Betancourt and Darrell Schweitzer and I decided that we’d like to revive Weird Tales. I had been editor of Amazing Stories. And they no longer wanted me. And I was getting bored. Anyway, we revived the magazine. And it’s been plunking along ever since. We’re up to Issue #20 — no, sorry, #340, with the issue that I have in my hot little hand right now. Which has stories by Jay Lake and Tanith Lee, Sarah Hoyt and Holly Phillips. We got interviewed by the Washington Post a little while ago. And the Los Angeles Times was good enough to pick up the article and run it also.

Correspondent: Now the new Weird Tales and the old Weird Tales. What are some of the overlapping kind of qualities? And what are the things that you’ve sort of changed to update Weird Tales? What have you been conscious of? What steps have you taken to do this?

Scithers: We’ve tried to put out what the magazine would be if it had continued, rather than digging it up and exhuming it. In other words, things have changed. When Weird Tales was first published, there was no such thing as science fiction. In the sense that the word had not even been invented. We carried science fiction — speculative fiction, if you will — as well as vampires and ghoulies and ghosts. We published the material of HP Lovecraft, who is unfortunately dead. So we can’t do any new stories by him. We published the original stories by Robert E. Howard. Conan the Conqueror and the like. And unfortunately, he’s dead. And we can’t do any more by him. And we also published Robert Bloch. And, alas, he’s dead too. And a few years ago, we published some poems by Ray Bradbury, who’s still alive actually.

Correspondent: Yes! Yes!

Scithers: But the modern science fiction stories are pretty well handled by specialized science fiction magazines. So that nowadays, Weird Tales has closed its scope a little bit. Basically supernatural horror. And every so often — because we must occasionally surprise the reader who expects everything to be supernatural — occasionally, the vampire may turn out to be a fake. Not every time. But, you know, every ten or fifteen years, we’ll run a story in which the ghost has a real explanation. Generally it’s a fantasy-based horror magazine. Or fantasy, which isn’t always horror. Sword and sorcery.

Correspondent: Now who would you say would be — which of your contributing writers would be the current sort of Lovecraft, Bloch, etcera. Or someone who has talent outside of that, but who is distinctive enough and yet also Weird Tales enough.

Scithers: That’s impossible to say. There isn’t any contemporary Lovecraft. Because Lovecraft was his own thing.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Scithers: And Lovecraft exhausted — well, didn’t exhaust, but worked over his particular mythos so well that it’s quite difficult to do another story in that now. And then someone does. But, again, in the current issue, Holly Phillips is a creature of her own. And that’s an entirely new thing. Tanith Lee has her own particular kind of fantasy. Which is not the same thing every time. She’s all over the place. I can’t really say that we’ve got one particular author. We’d love to have Stephen King all the time. But Stephen King does books these days. And we’re essentially a short story market.

Correspondent: Do you have problems? Because there’s always all these kinds of claims that the short story is dead. There are literary magazines that are just struggling to get by. Has any of this affected Weird Tales in terms of putting out issues or attracting talent? Maybe you can comment upon these issues.

Scithers: As far as the supply of short stories, no problem. If anything, there’s — I hate to say this, but we almost have too many writers in the field now. Our problem is that people do not go to cigar stores and magazine stores to the extent that they used to. Magazine circulation used to be in the hundreds of thousands. And then the tens and tens of thousands. And now in the low tens. And this is a problem throughout the fiction field. There aren’t an awful lot of fiction magazines. The Digest Group. Asimov’s, Analog, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. And on the other side, Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. All of these have decreasing circulation over the years. As far as the availability of material, the thing is that there are annual courses on how to teach science fiction. I’ve been publishing books on how to write science fiction. I’ve been publishing guidelines on science fiction. As far as the supply of good, good material, there’s plenty. I see a higher percentage of buyable material nowadays. Back in the Asimov’s days, when I first started in this line of work — which is about 1978 — I figured about 1% of what I got in would be fit to put on the page. I’m seeing a higher percentage of stuff that’s fit to put on the page. But I can’t buy all the stuff that’s fit to put on the page. Because there’s so much of it.

Correspondent: How much of a higher percentage are you seeing now?

Scithers: I can’t say a percentage. Because I’d have to sit down and count how many manuscripts, and how many got the “good but not irresistible” reply, and how many got the “please don’t keep making the same mistakes over and over again” reply, and how many got the “get a hold of Strunk & White and you better believe it.” Strunk & White is the essential book on composition, on how to write. It’s a thin volume. It’s extremely good. You learn the standard way to write. You change away from that for deliberate effect. You find that you’re disagreeing with it. And then, as you get better, you find that they were right all along. They are talking about the general case. And what you are writing is the special case. Typically, standard English is what you frame around dialogue. But what’s between the quote marks is how people actually speak. Which isn’t precisely literary. It isn’t precisely grammatical. And you vary from being precisely literary and grammatical in order to call attention to how people are speaking. In your exposition part of the story, if you want to call attention to what you’re doing, then you start breaking some of the rules. But if you drop into standard grammar, then all that comes across is “What words are you choosing? And in what order to you put them down?” Which are the basics of writing. It’s the basic poetry too, as Coleridge put it.

Correspondent: Well, going back to this issue of more manuscripts being suitable. It’s just a matter of finding the ones that are right for Weird Tales. Do you think that the rise of MFA workshops might have something to do with this?

Scithers: I don’t know MFA Workshop. Because I know that there are a great many workshops over the years, over the decades. So I’m not aware of what MFA Workshop is doing. Tell me about it.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: I think it’s great that Scithers thought that “MFA Workshop” was a specific outfit. He was very much an old school, nuts-and-bolts kind of guy.]

Correspondent: Well, you know, workshops for people who get MFA degrees in creative writing.

Scithers: Right.

Correspondent: And so there are all these workshops around short stories. And so therefore you have this cottage industry almost for aspiring writers, who are then perhaps flooding Weird Tales, along with the remaining literary magazines and journals that we have in order to get some credits. I’m sort of speculating out loud, but maybe….

Scithers: Of course you are. Of course you are. The thing about workshops is, if somebody’s off in a garret writing all by himself, he’ll start writing for himself. And this is not good. So working with other people is helpful. But you have to remember that the opinion of somebody who is close enough to you that you can hit them, is not as good as somebody on the far end of an email line. Or of a mail line. In the end, however, the only opinion that really matters is that of someone who might pay you money for it. [interjection by another guy at the booth] Somebody’s trying to interrupt us?

Correspondent: Well, George, thanks so much.

[Confused stare from George.]

Correspondent: Do you want to continue your answer?

Scithers: Uh no. Do you want to expand with the question?

Correspondent: Oh, well, I mean, I guess I was getting a sense of like: Do you think that the MFA mentality of an approval by committee is perhaps damaging. Particularly when we’re talking about genre fiction, like Weird Tales, where these MFA workshops….

Scithers: Ah yes! Yes, yes, yes! Your problem is that in the group, if someone is using the group for other than learning how to write, and helping other people to write, then you’re in trouble. And you have to keep your antenna out for just exactly this phenomenon. That if somebody is trying to dominate the group. Somebody’s trying to show how much better he is or how much less good — that’s not the point of a group. The group is: what does a group, in general, think is good and bad about what somebody is writing. If the group is turning over people who are becoming so busy selling, that they no longer have time for the group, that is a successful group. If the group is a static group who simply get together to argue with each other, you see, this is a kind of a trap. The bouncing things off of other people is a faster way of getting a feel for it than sending it off by mail. But the opinion you get back by somebody who might buy it, and thinks it was good enough to say what’s wrong with it, that’s important. The kind of things that I see over and over again is somebody starts with a resume. Well, I’m not buying a resume! I’m buying a story.

Correspondent: Unless the story is actually a horror resume.

Scithers: No. No! There is a general remark about this. That if you don’t get the reader’s attention in the first paragraph, the rest of the message is lost. This was written by a rear admiral, who presumably was not writing about fiction at the time. But it’s still very appropriate. The thing that a writer’s group should do is take a look at a story and say, “You know, if you start it in the second paragraph, it will be just as good.” Well, in fact, it would be a great deal better. Because the first paragraph is simply getting in your way. And starting the story too late, or not starting at all, are the most irritating things that come across. Other than things that are in such awful format that you have to just throw them back.

Correspondent: Well, George, thanks so much. These were all very interesting things to hear.

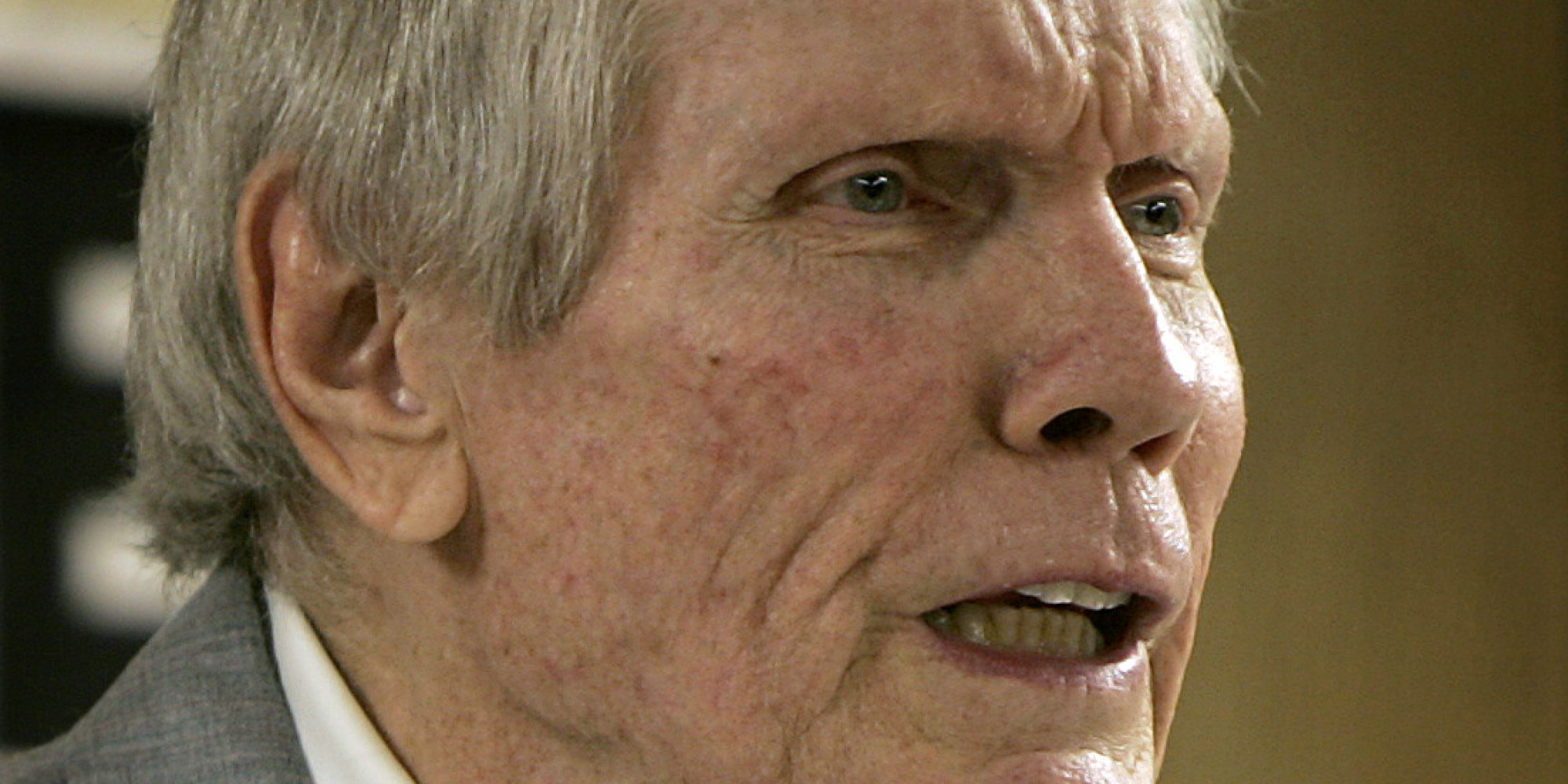

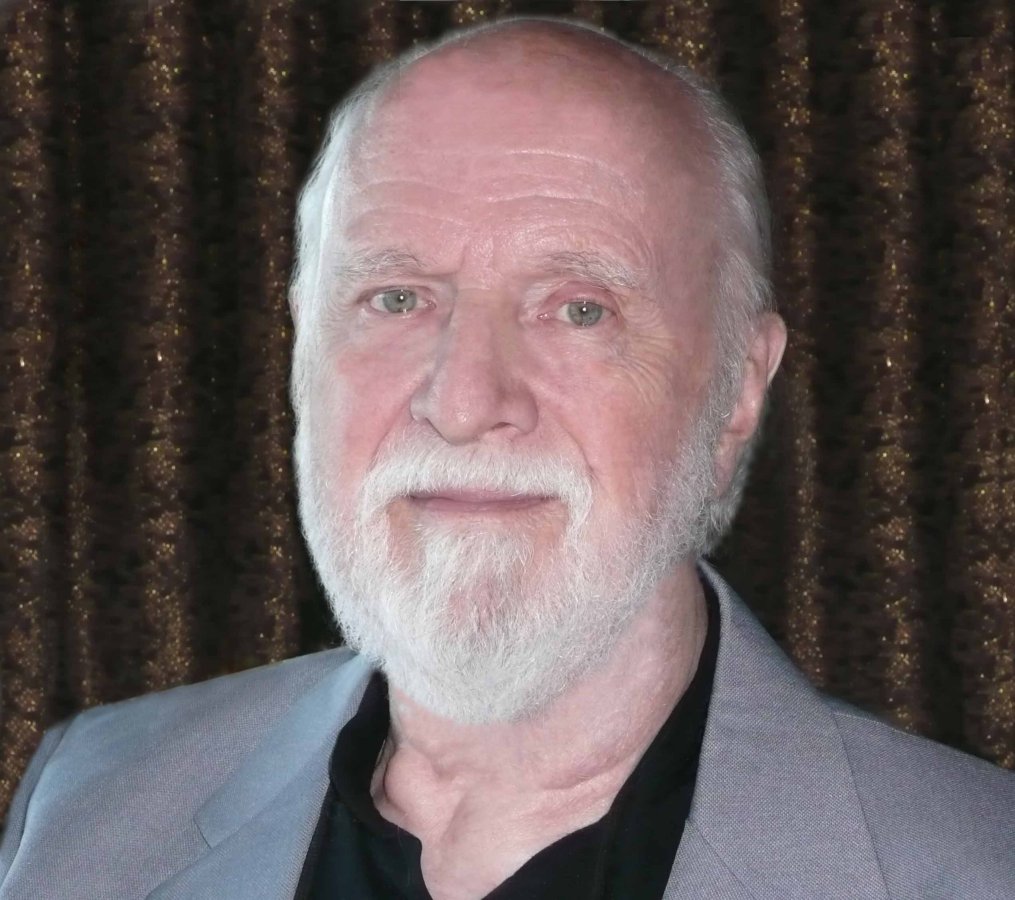

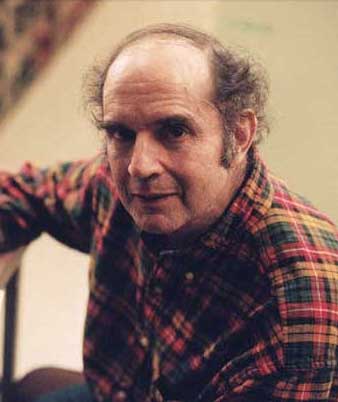

(Image: Darrell Schweitzer)

The Bat Segundo Show: George Scithers (2006) (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced