The Importance of ‘Carbon Storytelling’ in Future Sustainable Architecture

June 05, 2024 | Q&A with Luke Askwith, Giacomo Mari, and Kai Law

The shift in priority towards whole-life carbon in the last five years has been a seismic change for the industry, one we’re just starting to see the effects of in the buildings we live and work in. But unlike the cutting-edge sustainable buildings of the past — characterised by highly visible features like double skin facades and solar photovoltaic panels — tomorrow’s sustainable architecture will take advantage of initiatives that are inherently invisible: they will be leaner with less material in their construction; they will be designed to accommodate alternative future uses; and they will make greater use of existing materials and structures.

But this poses a key question: in a future where we will all be more aware of the carbon impacts of our buildings, yet many of these impacts will be inherently invisible to us, how can our buildings tell us their carbon ‘story’ in a way that we can recognise and understand?

It’s one of the questions I’ve been tackling over the last year with my colleagues, Giacomo Mari and Kai Law, as part of our research project exploring the future of the office. “We want to be able to tell the story in a way that’s relatable, that’s tangible, that’s impactful,” Kai says.

After talking with developers and designers, we have defined three ways that the low-carbon buildings of the future can communicate their strategy to end users:

1. Make carbon part of the identity of the building.

One of the first things we recognised was that, if the carbon initiatives in a building are going to be clear to users, they can’t be just an afterthought in the branding and storytelling process. The carbon story of a building needs to be part of its fundamental identity.

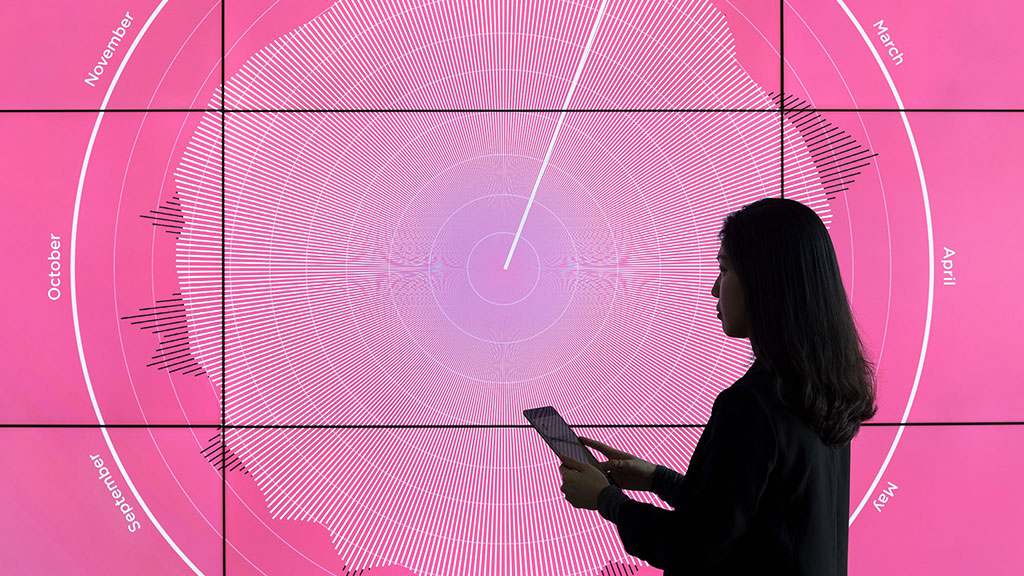

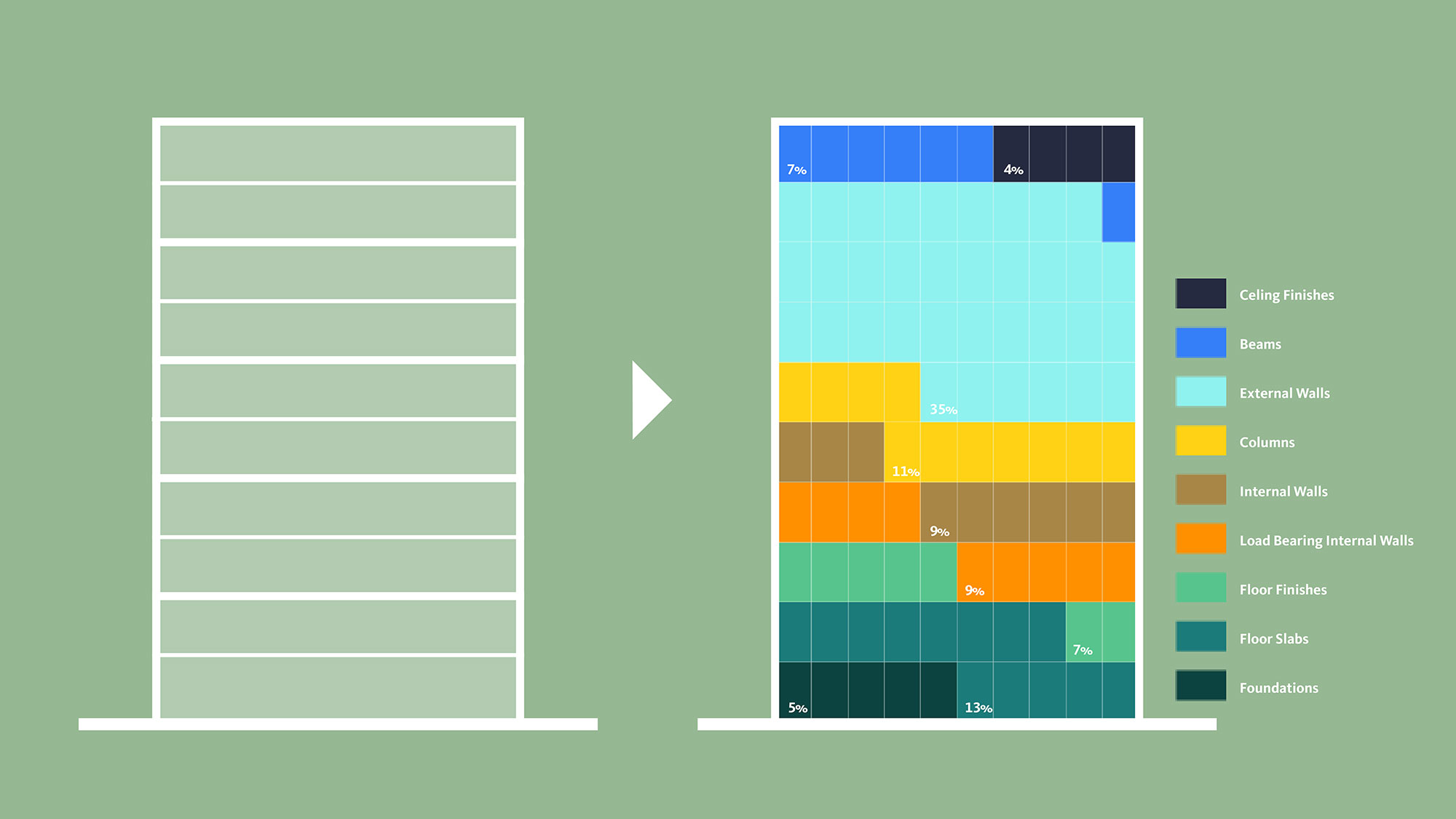

Kai and Giacomo explored the idea of summing up the embodied carbon performance of an office building in a simple graphic that not only presents the complex data in an accessible way but can also be used as the brand of the building itself.

“It is essentially a nutrition label for the building,” Kai explains. “It’s breaking down the building’s carbon impact into its raw ingredients and showing you the percentage makeup of its components. What we’re really trying to do is produce a carbon identity, which also acts as a building identity.”

The intention is that this graphic might be a prominent feature of public spaces in the building, in addition to informing the building’s graphic identity.

2. Keep the story personal.

The significance of kilograms of CO2 and their impact on global climate change will aways be challenging for many of us to grasp — and explaining carbon savings in terms of flights saved or trees planted will only go so far to improving this. In order to speak to users on a more personal level, buildings need to speak to the personal impact they have on people. It is essential that architects remember the perspective of the end users of the spaces they design.

“We don’t design for specialists, we design for everyone,” Giacomo says. “By highlighting how sustainable choices impact our health and well-being, occupants become more aware of the connection between the built environment and their personal life and their personal health.”

We identified key approaches to tell the sustainability story of any building in a way that’s more personal to users, including improving indoor air quality, increasing occupants’ awareness and education about the environmental impacts of their behaviours and lifestyle choices, and promoting social interaction through building-wide initiatives and engagement platforms.

3. Prioritise daily engagement.

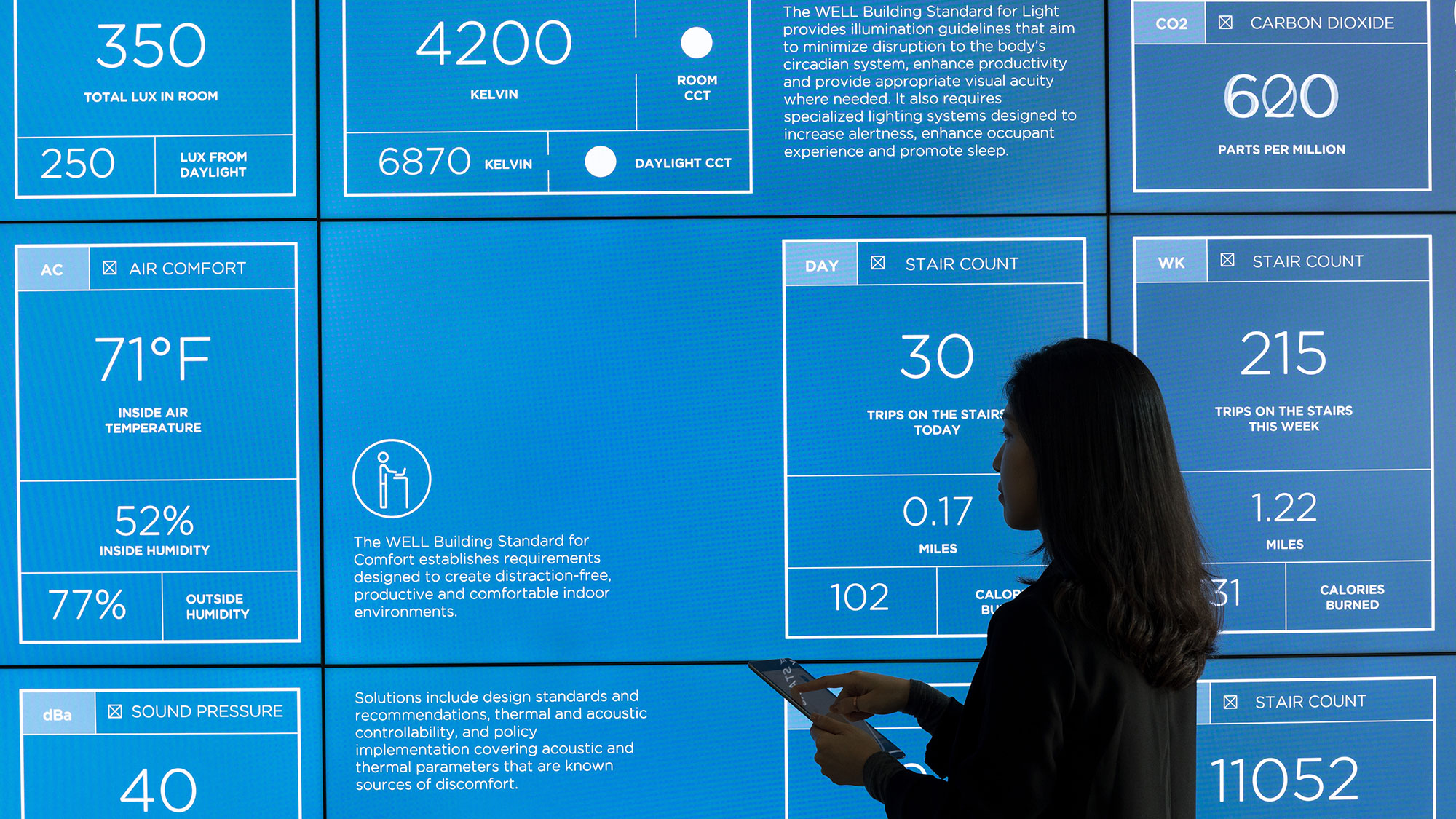

The smallest interactions with our buildings may be where we can have the biggest impacts with carbon storytelling. The team has designed a series of digital infographics to be positioned at key points around a building — giving information on how the building is performing and, crucially, how users’ daily engagement is affecting this performance.

For Kai, success comes down to making this story personal. “These digital infographics should be visual, they should be engaging, and they should really and most importantly demonstrate how the action will impact the building’s total operational carbon.”

Kai explained how there are certain times in your day when it’s acceptable for a building to ‘reach out’ and tell you about its sustainability performance. “For example, whilst I’m washing my hands, a digital graphic on the mirror can highlight how many cups of water is being used, poured, or wasted. It can help correlate the impact of my action to the consumption of water.”

“The carbon is part of the story of a building,” Giacomo says. “It’s not just numbers on a spreadsheet but it informs the shape and the nature of a building.”

It’s an approach we’ve implemented on our own projects, such as the Delos headquarters in New York, where the Gensler team created a branded digital experience that illustrates their mission by visualising building sensor data in a digital form that interacts with employees and guests. Ultimately, this project illustrates how we can take the highly technical, massively complex web of sustainability and carbon reduction strategies in any large building and present them in terms that are understandable, relatable, and engaging to occupants.

Building tenants and occupants are more aware than ever of the true environmental impact of the spaces that they inhabit — a trend that will continue for the foreseeable future. Future users will increasingly demand to know more about the true carbon impact of their buildings, and how it affects their personal health and well-being. By telling the carbon story of our buildings in an understandable and engaging way, developers and building owners can differentiate their buildings, while taking steps toward creating a more sustainable future.

For media inquiries, email .