Colonialism: Difference between revisions

Byrgenwulf (talk | contribs) →The French colonial empire: removed "y'a bon banania" *again*: IT IS NOT FRENCH! DO NOT REPLACE! |

m added back yet more edits rudely reverted by Lapaz |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

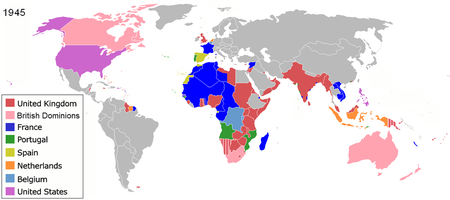

[[Image:Colonization 1945.png|thumb|right|300px|World map of colonialism at the end of the Second World War in 1945.]] |

[[Image:Colonization 1945.png|thumb|right|300px|World map of colonialism at the end of the Second World War in 1945.]] |

||

== Pre-15th Century, Non-European Colonization == |

== History of Colonialism == |

||

=== Pre-15th Century, Non-European Colonization === |

|||

A number of pre-15th Century, |

A number of pre-15th Century, non-European waves of imperialism and colonization occurred in differing places. The [[Mongol Empire]] was a large empire stretching from the Western [[Pacific]] to [[Eastern Europe]]. Across the [[Mediterranean]], [[North Africa]], [[Western Asia]] and [[Europe]] were created the following empires with primarily European and non-European rulers - the Empire of [[Alexander the Great]], the [[Umayyad Caliphate]], the [[Persian Empire]], the [[Roman Empire]], the [[Byzantine Empire]]. The [[Ottoman Empire]] was created across [[Mediterranean]], [[North Africa]] and into [[Southern Europe]] and existed also during the time of European colonization of the other parts of the world. |

||

== The first European colonization wave (15th century-19th century) == |

=== The first European colonization wave (15th century-19th century) === |

||

{{main|The first European colonization wave (15th century-19th century)}} |

{{main|The first European colonization wave (15th century-19th century)}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Main|Portuguese Empire|Portugal in the Age of Discovery|Spanish colonization of the Americas}} |

{{Main|Portuguese Empire|Portugal in the Age of Discovery|Spanish colonization of the Americas}} |

||

European colonisation of both [[Eastern Hemisphere|Eastern]] and [[Western Hemisphere]]s has its roots in [[Portugal|Portuguese]] exploration. There were financial and religious motives behind this exploration. By finding the source of the lucrative [[spice trade]], the Portuguese could reap its profits for themselves. They would also be able to probe the existence of the fabled Christian kingdom of [[Prester John]], with a view to encircling the Islamic [[Ottoman Empire]]. The first foothold outside of Europe was gained with the conquest of [[Ceuta]] in [[1415]]. During the fifteenth century Portuguese sailors discovered the Atlantic islands of [[Madeira]], [[Azores]], and [[Cape Verde]], which were duly populated, and pressed progressively further along the west African coast until [[Bartolomeu Dias]] demonstrated it was possible to sail around Africa by rounding the [[Cape of Good Hope]] in 1488, paving the way for [[Vasco da Gama]] to reach [[India]] in [[1498]]. |

European colonisation of both [[Eastern Hemisphere|Eastern]] and [[Western Hemisphere]]s has its roots in [[Portugal|Portuguese]] exploration. There were financial and religious motives behind this exploration. By finding the source of the lucrative [[spice trade]], the Portuguese could reap its profits for themselves. They would also be able to probe the existence of the fabled Christian kingdom of [[Prester John]], with a view to encircling the Islamic [[Ottoman Empire]]. The first foothold outside of Europe was gained with the conquest of [[Ceuta]] in [[1415]]. During the fifteenth century Portuguese sailors discovered the Atlantic islands of [[Madeira]], [[Azores]], and [[Cape Verde]], which were duly populated, and pressed progressively further along the west African coast until [[Bartolomeu Dias]] demonstrated it was possible to sail around Africa by rounding the [[Cape of Good Hope]] in 1488, paving the way for [[Vasco da Gama]] to reach [[India]] in [[1498]]. |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

The boundaries specified by the Treaty of Tordesillas were put to the test a second time when [[Ferdinand Magellan]], a Portuguese explorer sailing under the Spanish flag reached the [[Philippines]]. The two by now global empires, which had set out from opposing directions, had finally met on the other side of the world. |

The boundaries specified by the Treaty of Tordesillas were put to the test a second time when [[Ferdinand Magellan]], a Portuguese explorer sailing under the Spanish flag reached the [[Philippines]]. The two by now global empires, which had set out from opposing directions, had finally met on the other side of the world. |

||

=== The role of the Church === |

==== The role of the Church ==== |

||

{{Main|The Roman Catholic Church and Colonialism}} |

{{Main|The Roman Catholic Church and Colonialism}} |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

In the 1970s, the Jesuits would become a main proponent of the [[Liberation theology]] which openly supported anti-imperialist movements. It was officially condemned in 1984 and in 1986 by then [[cardinal Ratzinger]] (current [[Pope]]) as the head of the [[Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith]], under charges of [[Marxism|Marxist tendencies]], while [[Leonardo Boff]] was suspended. |

In the 1970s, the Jesuits would become a main proponent of the [[Liberation theology]] which openly supported anti-imperialist movements. It was officially condemned in 1984 and in 1986 by then [[cardinal Ratzinger]] (current [[Pope]]) as the head of the [[Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith]], under charges of [[Marxism|Marxist tendencies]], while [[Leonardo Boff]] was suspended. |

||

===Northern European challenges to the Iberian hegemony=== |

====Northern European challenges to the Iberian hegemony==== |

||

It was not long before the exclusivity of Iberian claims to the Americas was challenged by other up and coming European powers, primarily the [[Netherlands]], [[France]] and [[England]]: the view taken by the rulers of these nations is epitomized by the quotation attributed to [[Francis I of France]] demanding to be shown the clause in Adam's will excluding his authority from the New World. |

It was not long before the exclusivity of Iberian claims to the Americas was challenged by other up and coming European powers, primarily the [[Netherlands]], [[France]] and [[England]]: the view taken by the rulers of these nations is epitomized by the quotation attributed to [[Francis I of France]] demanding to be shown the clause in Adam's will excluding his authority from the New World. |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

However, the English, French and Dutch were no more averse to making a profit than the Spanish and Portuguese, and whilst their areas of settlement in the Americas proved to be devoid of the precious metals found by the Spanish, trade in other commodities and products that could be sold at massive profit in Europe provided another reason for crossing the Atlantic, in particular [[fur]]s from Canada, [[tobacco]] and [[cotton]] grown in [[Virginia]] and [[sugar]] in the islands of the Caribbean and Brazil. Due to the massive depletion of indigenous labour, plantation owners had to look elsewhere for manpower for these labour-intensive crops. They turned to the centuries old slave trade of west Africa and began transporting humans across the Atlantic on a massive scale - historians estimate that the [[Atlantic slave trade]] brought between 10 and 12 million individuals to the New World. The islands of the Caribbean soon came to be populated by slaves of African descent, ruled over by a white minority of plantation owners interested in making a fortune and then returning to their home country to spend it. |

However, the English, French and Dutch were no more averse to making a profit than the Spanish and Portuguese, and whilst their areas of settlement in the Americas proved to be devoid of the precious metals found by the Spanish, trade in other commodities and products that could be sold at massive profit in Europe provided another reason for crossing the Atlantic, in particular [[fur]]s from Canada, [[tobacco]] and [[cotton]] grown in [[Virginia]] and [[sugar]] in the islands of the Caribbean and Brazil. Due to the massive depletion of indigenous labour, plantation owners had to look elsewhere for manpower for these labour-intensive crops. They turned to the centuries old slave trade of west Africa and began transporting humans across the Atlantic on a massive scale - historians estimate that the [[Atlantic slave trade]] brought between 10 and 12 million individuals to the New World. The islands of the Caribbean soon came to be populated by slaves of African descent, ruled over by a white minority of plantation owners interested in making a fortune and then returning to their home country to spend it. |

||

===Rule in the colonies: the ''Leyes de Burgos'' and the ''Code Noir'' === |

====Rule in the colonies: the ''Leyes de Burgos'' and the ''Code Noir'' ==== |

||

{{main|Leyes de Burgos|Valladolid Controversy|Code Noir}} |

{{main|Leyes de Burgos|Valladolid Controversy|Code Noir}} |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

In the [[French colonial empires|French empire]], [[slavery|slave trade]] and other colonial rules were regulated by [[Louis XIV]]'s 1689 ''[[Code Noir]]''. |

In the [[French colonial empires|French empire]], [[slavery|slave trade]] and other colonial rules were regulated by [[Louis XIV]]'s 1689 ''[[Code Noir]]''. |

||

=== Role of companies in early colonialism === |

==== Role of companies in early colonialism ==== |

||

From its very outset, Western colonialism was operated as a joint public-private venture. Columbus' voyages to the Americas were partially funded by Italian investors, but whereas the Spanish state maintained a tight reign on trade with its colonies (by law, the colonies could only trade with one designated port in the mother country and treasure was brought back in special [[Spanish treasure fleet|convoys]]), the English, French and Dutch granted what were effectively trade [[monopolies]] to [[Joint stock company|joint-stock companies]] such as the [[East India Company|East India Companies]] and the [[Hudson's Bay Company]]. |

From its very outset, Western colonialism was operated as a joint public-private venture. Columbus' voyages to the Americas were partially funded by Italian investors, but whereas the Spanish state maintained a tight reign on trade with its colonies (by law, the colonies could only trade with one designated port in the mother country and treasure was brought back in special [[Spanish treasure fleet|convoys]]), the English, French and Dutch granted what were effectively trade [[monopolies]] to [[Joint stock company|joint-stock companies]] such as the [[East India Company|East India Companies]] and the [[Hudson's Bay Company]]. |

||

=== European colonies in India during the first wave of colonization === |

==== European colonies in India during the first wave of colonization ==== |

||

{{main|European colonies in India}} |

{{main|European colonies in India}} |

||

In 1498, the [[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] set foot in [[Goa]]. Rivalry among reigning European powers saw the entry of the [[Dutch Empire|Dutch]], [[British India|British]], [[French India|French]], [[Danish India|Danish]] among others. The fractured debilitated kingdoms of [[History of India|India]] were gradually taken over by the Europeans and indirectly controlled by puppet rulers. In 1600, Queen [[Elizabeth I]] accorded a [[charter]], forming the [[British East India Company|East India Company]] to trade with India and eastern Asia. The British landed in India in [[Surat]] in [[1624]]. By the 19th century, they had assumed direct and indirect control over most of India. |

In 1498, the [[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] set foot in [[Goa]]. Rivalry among reigning European powers saw the entry of the [[Dutch Empire|Dutch]], [[British India|British]], [[French India|French]], [[Danish India|Danish]] among others. The fractured debilitated kingdoms of [[History of India|India]] were gradually taken over by the Europeans and indirectly controlled by puppet rulers. In 1600, Queen [[Elizabeth I]] accorded a [[charter]], forming the [[British East India Company|East India Company]] to trade with India and eastern Asia. The British landed in India in [[Surat]] in [[1624]]. By the 19th century, they had assumed direct and indirect control over most of India. |

||

=== The destruction of the Amerindian population and the Atlantic slave trade === |

==== The destruction of the Amerindian population and the Atlantic slave trade ==== |

||

[[Image:Triangle trade.png|right|thumb|300px|[[Mercantilism]] in the 16th and 17th centuries helped create trade patterns such as the [[triangular trade]] — in which the [[Atlantic slave trade]] was included. [[Raw material]]s ([[sugar]],[[tobacco]] and [[cotton]]) were imported to the metropolis and then processed and redistributed to other colonies. Thus, the slaves were bought in Africa with [[textile]], [[rum]]s and other [[manufactured good]]s, and sold in the New World against raw materials. According to anti-colonialist critics, this exploitation of [[natural resources]] form the bases of today's terms of [[unequal exchange]] between nations <ref> See the [[Bolivian Gas War]] for a historical and current example of [[social conflict]] based on the popular revendications to process the gaz in the country itself instead of exporting it as a raw material </ref>.]] |

[[Image:Triangle trade.png|right|thumb|300px|[[Mercantilism]] in the 16th and 17th centuries helped create trade patterns such as the [[triangular trade]] — in which the [[Atlantic slave trade]] was included. [[Raw material]]s ([[sugar]],[[tobacco]] and [[cotton]]) were imported to the metropolis and then processed and redistributed to other colonies. Thus, the slaves were bought in Africa with [[textile]], [[rum]]s and other [[manufactured good]]s, and sold in the New World against raw materials. According to anti-colonialist critics, this exploitation of [[natural resources]] form the bases of today's terms of [[unequal exchange]] between nations <ref> See the [[Bolivian Gas War]] for a historical and current example of [[social conflict]] based on the popular revendications to process the gaz in the country itself instead of exporting it as a raw material </ref>.]] |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

Stannard's claim of 100 million deaths has been disputed because he makes no distinction between death from violence and death from disease. In response, [[political science|political scientist]] [[R. J. Rummel]] has instead estimated that over the centuries of European colonization about 2 million to 15 million American indigenous people were the victims of what he calls ''[[democide]].'' "Even if these figures are remotely true," writes Rummel, "then this still make this subjugation of the Americas one of the bloodier, centuries long, democides in world history." <ref> Cf. [[R. J. Rummel]]'s quote and estimate from [http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/DBG.CHAP3.HTM his website], about midway down the page, after footnote 82. Rummel's estimate is presumably not a single democide, but a total of multiple democides, since there were many different governments involved.</ref> |

Stannard's claim of 100 million deaths has been disputed because he makes no distinction between death from violence and death from disease. In response, [[political science|political scientist]] [[R. J. Rummel]] has instead estimated that over the centuries of European colonization about 2 million to 15 million American indigenous people were the victims of what he calls ''[[democide]].'' "Even if these figures are remotely true," writes Rummel, "then this still make this subjugation of the Americas one of the bloodier, centuries long, democides in world history." <ref> Cf. [[R. J. Rummel]]'s quote and estimate from [http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/DBG.CHAP3.HTM his website], about midway down the page, after footnote 82. Rummel's estimate is presumably not a single democide, but a total of multiple democides, since there were many different governments involved.</ref> |

||

==Independence in the Americas== |

===Independence in the Americas=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

During the five decades following 1770, Britain, France, Spain and Portugal lost their most valuable colonies in the Americas. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{main|Thirteen Colonies|American Revolutionary War|United States Declaration of Independence}} |

{{main|Thirteen Colonies|American Revolutionary War|United States Declaration of Independence}} |

||

After the conclusion of the [[Seven Years' War]] in 1763, Britain had emerged as the world's dominant power, but found itself mired in debt and struggling to finance the Navy and Army necessary to maintain a global empire. The [[British Parliament]]'s attempt to raise taxes on the North American colonists raised fears among the Americans that their rights as "Englishmen," particularly their rights of self-government, were in danger. A series of disputes with Parliament over taxation led first to informal [[committees of correspondence]] among the colonies, then to coordinated protest and resistance, and finally to the [[United States Declaration of Independence|Declaration of Independence]] on July 4, 1776, by the Second [[Continental Congress]]. |

After the conclusion of the [[Seven Years' War]] in 1763, Britain had emerged as the world's dominant power, but found itself mired in debt and struggling to finance the Navy and Army necessary to maintain a global empire. The [[British Parliament]]'s attempt to raise taxes on the North American colonists raised fears among the Americans that their rights as "Englishmen," particularly their rights of self-government, were in danger. A series of disputes with Parliament over taxation led first to informal [[committees of correspondence]] among the colonies, then to coordinated protest and resistance, and finally to the [[United States Declaration of Independence|Declaration of Independence]] on July 4, 1776, by the Second [[Continental Congress]]. |

||

===The Haitian Revolution |

====France and The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804)==== |

||

{{main|Haitian Revolution|Abolitionism}} |

|||

The [[Haïtian Revolution]], a slave revolt led by [[Toussaint L'Ouverture]] in the the French colony of '''[[Saint-Domingue]]''', established [[Haïti]] as a free, black [[republic]], the first of its kind, and the second independent nation in the [[Western Hemisphere]] after the United States. Africans and people of African ancestry freed themselves from slavery and colonization by taking advantage of the conflict among whites over how to implement the reforms of the [[French Revolution]] in this slave society. Although independence was declared in 1804, it was not until 1825 that it was formally recognised by [[King Charles X]] of France. |

|||

The 1791 [[Haitian Revolution]], led by [[Toussaint L'Ouverture]], gives the first example of the constitution of a black [[Republic]] and of the [[abolitionism|abolition of slavery]]. The rebels imposed to the [[French First Republic|First Republic]] (1792-1804) the repeal of slavery, regulated by the 1689 ''[[Code Noir]]'', on [[February 4]], [[1794]]. The [[Henri Grégoire|Abbé Grégoire]] and the [[Society of the Friends of the Blacks]], led by [[Jacques Pierre Brissot]], were part of the abolitionist movement, which had laid important groundwork in building anti-slavery sentiment in the metropole. The first article of the law stated that "Slavery was repealed" in the French colonies, while the second article stated that "slave-owners would be indemnified", with a financial compensation. On [[May 10]], [[1802]], [[Louis Delgrès|colonel Delgrès]] signed a public notice, which was a call to Guadeloupe for [[insurgency]] against [[Antoine Richepanse|general Richepanse]], sent by [[Napoleon]] to reestablish slavery. The rebellion was repressed, and slavery reestablished. It would be definitely abolished on [[April 27]], [[1848]], by the [[decree-law]] [[Victor Schoelcher|Schœlcher]] under the [[French Second Republic|Second Republic]] (1848-52). Slaves were bought back to the colons (''[[Békés]]'' in [[Creole language|Creole]]) and then freed by the state. However, at the same moment, France started participating in the [[scramble for Africa]], [[population transfer|transferring the population]] to the [[mining|mines]], the [[forestry]] and [[rubber]] plantations. |

|||

===Wars of Independence in Latin America === |

====Spain and the Wars of Independence in Latin America ==== |

||

{{main|South American Wars of Independence|Mexican War of Independence}} |

{{main|South American Wars of Independence|Mexican War of Independence}} |

||

The Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821) and the various Wars of Independence led in the 1810s and 1820s by famous ''[[Libertadores]]'' such as [[José de San Martin]] in the South or [[Simón Bolívar]] in the North, brought to most Latin American countries independence from the European powers. |

The Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821) and the various Wars of Independence led in the 1810s and 1820s by famous ''[[Libertadores]]'' such as [[José de San Martin]] in the South or [[Simón Bolívar]] in the North, brought to most Latin American countries independence from the European powers. |

||

| Line 111: | Line 113: | ||

{{sectstub}} |

{{sectstub}} |

||

===Brazil=== |

====Portugal and Brazil==== |

||

Brazil was the only country in Latin America to gain its independence without bloodshed. The invasion of Portugal by [[Napoleon]] in 1808 had forced the King Joao VI to flee to Brazil and establish his court in Rio de Janeiro. For thirteen years, Portugal was ruled from Brazil (the only instance of such a reversal of roles between colony and metropole) until his return to Portugal in 1821. His son, Dom Pedro, was left in charge of Brazil and in 1822 he declared independence from Portugal and himself the Emporer of Brazil. Unlike Spain's former colonies which had abandoned the monarchy in favour of republicanism, Brazil therefore retained its links with its monarchy, the [[House of Braganza]]. |

|||

{{sectstub}} |

|||

==The second European colonization wave in the 19th-20th century == |

===The second European colonization wave in the 19th-20th century === |

||

{{main|The Second European colonization wave (19th-20th century)}} |

{{main|The Second European colonization wave (19th-20th century)}} |

||

=== The New Imperialism === |

==== The New Imperialism ==== |

||

{{Main|New Imperialism|Rise of the New Imperialism|Scramble for Africa}} |

{{Main|New Imperialism|Rise of the New Imperialism|Scramble for Africa}} |

||

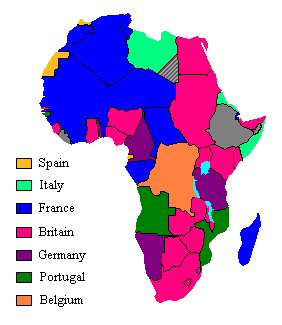

| ⚫ | The latter half of 19th century saw the transition from an "informal" empire of control through military and economic dominance to direct control, marked from the [[1870s]] on by the scramble for territory in areas previously regarded as merely under Western influence. Colonialism would take its full extent only during the period known as [[New Imperialism]], starting in the 1860s with the [[Scramble for Africa]]. |

||

====Rise of the New Imperialism==== |

|||

{{Main|New Imperialism|Rise of the New Imperialism}} |

|||

| ⚫ | The latter half of 19th century saw the transition from an "informal" empire of control through military and economic dominance to direct control, marked from the [[1870s]] on by the scramble for territory in areas previously regarded as merely under Western influence. Colonialism would take its full extent only during the period known as [[New Imperialism]], starting in the 1860s with the [[Scramble for Africa]] |

||

The [[Berlin Conference]] (1884 - 1885) mediated the imperial competition among |

The [[Berlin Conference]] (1884 - 1885) mediated the imperial competition among Britain, France and Germany, defining "effective occupation" as the criterion for international recognition of colonial claims and codifying the imposition of [[direct rule]], accomplished usually through armed force. |

||

A decade later, rival imperialisms would collide in the 1898 [[Fashoda Incident]], during which war between France and |

A decade later, rival imperialisms would collide in the 1898 [[Fashoda Incident]], during which war between France and Britain was barely avoided. This fear led to new alliances, and in 1904 the ''[[Entente Cordiale]]'' was signed between both powers. Imperialistic rivalry between the European powers would a main cause of the triggering of [[World War I]] in 1914. |

||

In Germany, rising [[pan-germanism]] was coupled to imperialism in the ''[[Alldeutsche Verband]]'' ("Pangermanic League"), which argued that Britain's world power position gave the British unfair advantages on international markets, thus limiting Germany's economic growth and threatening its security |

In Germany, rising [[pan-germanism]] was coupled to imperialism in the ''[[Alldeutsche Verband]]'' ("Pangermanic League"), which argued that Britain's world power position gave the British unfair advantages on international markets, thus limiting Germany's economic growth and threatening its security. |

||

====North America in the 19th century ==== |

====North America in the 19th century ==== |

||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

{{Main|Scramble for Africa}} |

{{Main|Scramble for Africa}} |

||

Many European statesmen and industrialists wanted to accelerate the [[Scramble for Africa]], securing colonies before they strictly needed them. The |

Many European statesmen and industrialists wanted to accelerate the [[Scramble for Africa]], securing colonies before they strictly needed them. The champion of [[Realpolitik]], [[Otto von Bismarck|Bismarck]] thus pushed a [[Weltpolitik]] vision ("World Politic"), which considered the colonization as a necessity for the emerging German power. German colonies in [[Togo]]land, [[Samoa]], [[South-West Africa]] and [[New Guinea]] had corporate commercial roots, while the equivalent German-dominated areas in [[East Africa]] and [[China]] owed more to political motives. The British also took an interest in Africa, using the East Africa company to take over Kenya and Uganda. The British crown formally took over in 1895 and renamed the area the East Africa Protectorate. |

||

[[Image:Herero chained.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Herero]] chained during the 1904 rebellion, before the [[Herero Genocide]] (1904-07) in [[German South-West Africa]] (finally independent, under the name of [[Namibia]], in 1990).]] |

[[Image:Herero chained.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Herero]] chained during the 1904 rebellion, before the [[Herero Genocide]] (1904-07) in [[German South-West Africa]] (finally independent, under the name of [[Namibia]], in 1990).]] |

||

| Line 157: | Line 157: | ||

The [[Portuguese colonial empire|Portuguese]] and [[Spanish colonial empire]] were smaller, mostly legacies of past colonization. Most of their colonies had acquired independence during the [[Latin American revolutions]] at the beginning of the 19th century. |

The [[Portuguese colonial empire|Portuguese]] and [[Spanish colonial empire]] were smaller, mostly legacies of past colonization. Most of their colonies had acquired independence during the [[Latin American revolutions]] at the beginning of the 19th century. |

||

== German colonialism == |

==== German colonialism ==== |

||

{{main|German colonialism}} |

{{main|German colonialism}} |

||

| Line 169: | Line 169: | ||

{{See|Aftermath of World War I|League of Nations Mandate}} |

{{See|Aftermath of World War I|League of Nations Mandate}} |

||

The colonial |

The colonial map was redrawn following the defeat of Germany and the [[Ottoman Empire]] after the [[first World War]] (1914-18). Colonies from the defeated empires were transferred to the newly founded [[League of Nations]], which itself redistributed it to the victorious powers as [[League of Nations Mandate|"mandates"]]. |

||

The twentieth century saw the era of the [[banana republic]]s, in particular in [[Latin America]], whereby corporations such as [[United Fruit]] or [[Standard Fruit]] dominated the economies and sometimes the politics of parts of [[Latin America]]. The United Fruit, nicknamed 'The Octopus' for its willingness to involve itself in politics, was present in most American countries and was involved in several coups, in [[Honduras]] and elsewhere. 1971 [[Nobel prize for literature|Nobel prize]] for literature winner [[Pablo Neruda]] would later denounce such [[neocolonialism]] in a poem titled ''La United Fruit Co''. |

The twentieth century saw the era of the [[banana republic]]s, in particular in [[Latin America]], whereby corporations such as [[United Fruit]] or [[Standard Fruit]] dominated the economies and sometimes the politics of parts of [[Latin America]]. The United Fruit, nicknamed 'The Octopus' for its willingness to involve itself in politics, was present in most American countries and was involved in several coups, in [[Honduras]] and elsewhere. 1971 [[Nobel prize for literature|Nobel prize]] for literature winner [[Pablo Neruda]] would later denounce such [[neocolonialism]] in a poem titled ''La United Fruit Co''. |

||

| Line 175: | Line 175: | ||

[[Petroleum|Oil]] companies such as [[BP]] and [[Royal Dutch Shell]] held sway in "key" areas such as parts of [[Iran]] and of [[Nigeria]], despite the preservation of de jure independence. |

[[Petroleum|Oil]] companies such as [[BP]] and [[Royal Dutch Shell]] held sway in "key" areas such as parts of [[Iran]] and of [[Nigeria]], despite the preservation of de jure independence. |

||

=== Middle East === |

==== Middle East ==== |

||

{{Main|League of Nations Mandate|History of Palestine}} |

{{Main|League of Nations Mandate|History of Palestine}} |

||

| Line 190: | Line 190: | ||

[[Pan-Arabism]] was a popular anti-imperialist ideology in the 1960s, and [[Nasserism]] favorized the merging of [[Egypt]] and [[Syria]] into the [[United Arab Republic]] (1958-61). The short term [[Arab Federation of Iraq and Jordan]] (1958) also attempted to bypass the 1920s artificial borders. Pan-Arabism was however defeated with the 1967 Six-Day War and the emergence of [[Islamism]] in the 1980s as a popular substitution to [[secularism|secular]] [[Arab nationalism]], as represented for example by the [[Baath Party]]. |

[[Pan-Arabism]] was a popular anti-imperialist ideology in the 1960s, and [[Nasserism]] favorized the merging of [[Egypt]] and [[Syria]] into the [[United Arab Republic]] (1958-61). The short term [[Arab Federation of Iraq and Jordan]] (1958) also attempted to bypass the 1920s artificial borders. Pan-Arabism was however defeated with the 1967 Six-Day War and the emergence of [[Islamism]] in the 1980s as a popular substitution to [[secularism|secular]] [[Arab nationalism]], as represented for example by the [[Baath Party]]. |

||

=== Japanese imperialism === |

==== Japanese imperialism ==== |

||

{{sectstub}} |

{{sectstub}} |

||

{{main|Japanese imperialism|Imperialism in Asia}} |

{{main|Japanese imperialism|Imperialism in Asia}} |

||

| Line 200: | Line 200: | ||

In 1931 Japanese army units based in [[Manchuria]] seized control of the region; full-scale war with China followed in 1937, drawing Japan toward an overambitious bid for Asian hegemony (Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere), which ultimately led to defeat and the loss of all its overseas territories after World War II (see Japanese expansionism and Japanese nationalism). As in Korea, the Japanese treatment of the Chinese people was particularly brutal as exemplified by the Nanjing Massacre. |

In 1931 Japanese army units based in [[Manchuria]] seized control of the region; full-scale war with China followed in 1937, drawing Japan toward an overambitious bid for Asian hegemony (Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere), which ultimately led to defeat and the loss of all its overseas territories after World War II (see Japanese expansionism and Japanese nationalism). As in Korea, the Japanese treatment of the Chinese people was particularly brutal as exemplified by the Nanjing Massacre. |

||

=== The French colonial empire === |

==== The French colonial empire ==== |

||

{{main|French colonial empire}} |

{{main|French colonial empire}} |

||

Revision as of 22:32, 26 September 2006

See colony and colonisation for examples of colonialism which do not refer to Western colonialism.

Colonialism is the extension of a nation's sovereignty over territory beyond its borders by the establishment of either settler colonies or administrative dependencies in which indigenous populations are directly ruled or displaced. Colonizers generally dominate the resources, labor, and markets of the colonial territory and may also impose socio-cultural, religious and linguistic structures on the conquered population (see also cultural imperialism). However, though colonialism is often used interchangeably with imperialism, the latter is sometimes used more broadly as it covers control exercised informally (via influence) as well as formally. The term colonialism may also be used to refer to a set of beliefs used to legitimize or promote this system. Colonialism was often based on the belief that the mores and values of the colonizer are initially superior to those of the colonized (which may be perceived as ethnocentric). Some observers link such beliefs regarding values to racism, and to pseudo-scientific theories at the end of the 19th century, although this can be misleading since racism is by definition specifically about race, not values.

The historical phenomenon of colonisation is one that stretches around the globe and across time, including such disparate peoples as the Hittites, the Incas and the British, although the term "colonialism" is normally specific to European empires or seeks to draw a comparison with those Empires.

European colonisation may be broadly divided into two large waves, the first one starting with the "Age of Exploration" and the beginning of the Columbian Exchange, and the second one beginning in the second part of the 19th century with the New Imperialism period. Colonisation and decolonisation have overlapped themselves, since most of the New World colonies had already acquired their independence when the scramble for Africa and the New Imperialism began.

Types of colonialism

Settler colonies, dependencies, plantations colonies, trading posts

There are many types of colonialism in the World which may be distinguished, according to the form of colonization and also the date. Settler colonies, such as the original thirteen states of the United States of America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina and Soviet policies in Siberia arose from the emigration of peoples from a metropole, or mother country, and involved displacement of the indigenous peoples to their permanent detriment [1]. Settler colonies may be contrasted with dependencies, where the colonizers did not arrive as part of a mass emigration, but rather as administrators over existing sizeable native populations, exercising control by use or threat of force. Examples in this category include the British Raj, Egypt, the Dutch East Indies, and the Japanese colonial empire. In some cases large-scale colonial settlement was attempted in substantially pre-populated areas and the result was either an ethnically mixed population (such as the mestizos of the Americas), or racially divided, such as in French Algeria or Southern Rhodesia. A third category may be considered in the cases where large-scale colonial settlement was attempted in substantially pre-populated areas: the result was either an ethnically mixed population (such as the mestizos of the Americas), or racially divided, such as in French Algeria or Southern Rhodesia. A fourth category may be considered for plantation colonies such as Barbados, Saint-Domingue and Jamaica where the white colonizers imported black slaves who rapidly began to outnumber their owners, leading to minority rule, similar to a dependency. Trading posts, such as Macau, Malacca, Deshima and Singapore constitute a fifth category, where the primary purpose of the colony was to engage in trade rather than as a staging post for further colonization of the hinterland.

History of Colonialism

Pre-15th Century, Non-European Colonization

A number of pre-15th Century, non-European waves of imperialism and colonization occurred in differing places. The Mongol Empire was a large empire stretching from the Western Pacific to Eastern Europe. Across the Mediterranean, North Africa, Western Asia and Europe were created the following empires with primarily European and non-European rulers - the Empire of Alexander the Great, the Umayyad Caliphate, the Persian Empire, the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire. The Ottoman Empire was created across Mediterranean, North Africa and into Southern Europe and existed also during the time of European colonization of the other parts of the world.

The first European colonization wave (15th century-19th century)

Iberian exploration and colonization

European colonisation of both Eastern and Western Hemispheres has its roots in Portuguese exploration. There were financial and religious motives behind this exploration. By finding the source of the lucrative spice trade, the Portuguese could reap its profits for themselves. They would also be able to probe the existence of the fabled Christian kingdom of Prester John, with a view to encircling the Islamic Ottoman Empire. The first foothold outside of Europe was gained with the conquest of Ceuta in 1415. During the fifteenth century Portuguese sailors discovered the Atlantic islands of Madeira, Azores, and Cape Verde, which were duly populated, and pressed progressively further along the west African coast until Bartolomeu Dias demonstrated it was possible to sail around Africa by rounding the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, paving the way for Vasco da Gama to reach India in 1498.

Portuguese successes led to Spanish financing of a mission by Christopher Columbus in 1492 to explore an alternative route to Asia, by sailing west. When Columbus eventually made landfall in what are now called the Bahamas he believed he had reached the coast of Japan, but had in fact "discovered" the peripheral islands of a new continent, the Americas.

After Columbus' return to Europe, competing Spanish and Portuguese claims to undiscovered lands were settled in 1494 with the Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided the world outside of Europe in an exclusive duopoly between the Iberian kingdoms along a north-south meridian 370 leagues west of Cape Verde. Technically this meant that all of the Americas were open to Spanish colonization, but when Pedro Alvares Cabral's voyage to India was blown off course and landfall made on the Brazilian coast, this accident of navigation and an inability at the time to accurately measure longitude meant that Brazil ended up within the Portuguese half.

During the 16th century the Portuguese continued to press eastwards into Asia, making the first direct contact between Europeans and the peoples inhabiting present day countries such as Mozambique, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Indonesia, East Timor (1512), China, and finally Japan), whilst the Spanish conquistadores pressed into the American hinterland, establishing the vast Viceroyalties of New Spain, New Granada and Peru. The Portuguese, encountering ancient and well populated societies, established a seaborne empire consisting of armed coastal trading posts along their trade routes (such as Goa, Malacca and Macau) whereas Spanish colonization involved the emigration of large numbers of settlers, soldiers and administrators intent on owning land and exploiting the relatively primitive (by Old World standards) native population. The result was that where the Portuguese had relatively little cultural impact on the societies they forced their way into trading with, Spanish settlement of the New World was catastrophic: native peoples were no match for Spanish technology, ruthlessness or their diseases which decimated the indigenous population.

Both Spain and Portugal profited handsomely from their new found overseas colonies: the Spanish from gold and silver from mines such as Potosí and Zacateca, the Portuguese from the huge markups they enjoyed as trade intermediaries, particarlarly during the Namban trade period. The influx of precious metals to the Spanish monarchy's coffers allowed it to finance costly religious wars in Europe which ultimately proved its undoing: the supply of metals was not infinite and the large inflow caused inflation.

The boundaries specified by the Treaty of Tordesillas were put to the test a second time when Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer sailing under the Spanish flag reached the Philippines. The two by now global empires, which had set out from opposing directions, had finally met on the other side of the world.

The role of the Church

Religious zeal played a large role in Spanish and Portuguese overseas activities. While the Pope himself was a political power to be heeded (as evidenced by his authority to decree whole continents open to colonization by particular kings), the Church also sent missionaries to convert to the Catholic faith the "savages" of other continents. Thus, the 1481 Papal Bull Aeterni regis granted all lands south of the Canary Islands to Portugal, while in May 1493 the Spanish-born Pope Alexander VI decreed in the Bull Inter caetera that all lands west of a meridian only 100 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands should belong to Spain while new lands discovered east of that line would belong to Portugal. These arrangements were later precised with the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas.

The Dominicans and Jesuits, notably Francis Xavier in Asia, were particularly active in this endeavour. Many buildings erected by the Jesuits still stand, such as the Cathedral of Saint Paul in Macau and the Santisima Trinidad de Paraná in Paraguay, an example of a Jesuit Reduction.

Spanish treatment of the indigenous populations provoked a fierce debate at home in 1550-51, dubbed the Valladolid Controversy, over whether Indians possessed souls and if so, whether they were entitled to the basic rights of mankind. Bartolomé de Las Casas, author of A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, championed the cause of the natives, and was opposed by Sepúlveda, who claimed Amerindians were "natural slaves".

The School of Salamanca, which gathered theologians such as Francisco de Vitoria (1480-1546) or Francisco Suárez (1548-1617), argued in favor of the existence of natural law, which thus gave some rights to indigenous people. However, while the School of Salamanca limited Charles V's imperial powers over colonized people, they also legitimized the conquest, defining the conditions of "Just War". For example, these theologians admitted the existence of the right for indigenous people to reject religious conversion, which was a novelty for Western philosophical thought. However, Suárez also conceived many particular cases — a casuistry — in which conquest was legitimized. Hence, war was justified if the indigenous people refused free transit and commerce to the Europeans; if they forced converts to return to idolatry; if there come to be a sufficient number of Christians in the newly discovered land that they wish to receive from the Pope a Christian government; if the indigenous people lacked just laws, magistrates, agricultural techniques, etc. In any case, title taken according to this principle must be exercised with Christian charity, warned Suárez, and for the advantage of the Indians. Henceforth, the School of Salamanca legitimized the conquest while at the same time limiting the absolute power of the sovereign, which was celebrated in others parts of Europe under the notion of the divine right of kings.

In the 1970s, the Jesuits would become a main proponent of the Liberation theology which openly supported anti-imperialist movements. It was officially condemned in 1984 and in 1986 by then cardinal Ratzinger (current Pope) as the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, under charges of Marxist tendencies, while Leonardo Boff was suspended.

Northern European challenges to the Iberian hegemony

It was not long before the exclusivity of Iberian claims to the Americas was challenged by other up and coming European powers, primarily the Netherlands, France and England: the view taken by the rulers of these nations is epitomized by the quotation attributed to Francis I of France demanding to be shown the clause in Adam's will excluding his authority from the New World.

This challenge initially took the form of piratical attacks (such as those by Francis Drake) on Spanish treasure fleets or coastal settlements, but later the Northern European countries began establishing settlements of their own, primarily in areas that were outside of Spanish interests, such as what is now the eastern seaboard of the USA and Canada, or islands in the Caribbean, such as Aruba, Martinique and Barbados, that had been abandoned by the Spanish in favour of the mainland and larger islands.

Whereas Spanish colonialism was based on the religious conversion and exploitation of local populations via encomiendas (many Spaniards emigrated to the Americas to elevate their social status, and were not interested in manual labour), Northern European colonialism was bolstered by people fleeing religious persection or intolerance (for example, the Mayflower voyage). The motive for emigration was not to become an aristocrat or to spread one's faith but to start afresh in a new society, where life would be hard but one would be free to exercise one's religious beliefs. The most populous emigration of the 17th century was that of the English, who after a series of wars with the Dutch and French came to dominate the eastern coast of the present day USA and Canada.

However, the English, French and Dutch were no more averse to making a profit than the Spanish and Portuguese, and whilst their areas of settlement in the Americas proved to be devoid of the precious metals found by the Spanish, trade in other commodities and products that could be sold at massive profit in Europe provided another reason for crossing the Atlantic, in particular furs from Canada, tobacco and cotton grown in Virginia and sugar in the islands of the Caribbean and Brazil. Due to the massive depletion of indigenous labour, plantation owners had to look elsewhere for manpower for these labour-intensive crops. They turned to the centuries old slave trade of west Africa and began transporting humans across the Atlantic on a massive scale - historians estimate that the Atlantic slave trade brought between 10 and 12 million individuals to the New World. The islands of the Caribbean soon came to be populated by slaves of African descent, ruled over by a white minority of plantation owners interested in making a fortune and then returning to their home country to spend it.

Rule in the colonies: the Leyes de Burgos and the Code Noir

The January 27, 1512 Leyes de Burgos codified the laws for the government of the indigenous people of the New World, since the common law of Spain wasn't applied in these recently discovered territories. The scope of the laws were originally restricted to the island of Hispaniola, but were later extended to Puerto Rico and Jamaica. They authorized and legalized the colonial practice of creating encomiendas, where Indians were grouped together to work under colonial masters, limiting the size of these establishments to a minimum of 40 and a maximum of 150 people. The document finally prohibited the use of any form of punishment by the encomenderos, reserving it for officials established in each town for the implementation of the laws. It also ordered that the Indians be catechesized, outlawed bigamy, and required that the huts and cabins of the Indians be built together with those of the Spanish. It respected, in some ways, the traditional authorities, granting chiefs exemptions from ordinary jobs and granting them various Indians as servants. To poor fullfillment of the laws in many cases lead to inummerable protests and claims. In fact, the laws were so often poorly applied that they were seen as simply a legalization of the previous poor situation. This would create momentum for reform, carried out through the Leyes Nuevas ("New Laws") in 1542. Ten years later, Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas would publish A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, in the midst of the Valladolid Controversy, a debate about the existence or not of souls in Amerindians bodies. Las Casas, bishop of Chiapas, was opposed to Sepúlveda, who claimed Amerindians were "natural slaves".

In the French empire, slave trade and other colonial rules were regulated by Louis XIV's 1689 Code Noir.

Role of companies in early colonialism

From its very outset, Western colonialism was operated as a joint public-private venture. Columbus' voyages to the Americas were partially funded by Italian investors, but whereas the Spanish state maintained a tight reign on trade with its colonies (by law, the colonies could only trade with one designated port in the mother country and treasure was brought back in special convoys), the English, French and Dutch granted what were effectively trade monopolies to joint-stock companies such as the East India Companies and the Hudson's Bay Company.

European colonies in India during the first wave of colonization

In 1498, the Portuguese set foot in Goa. Rivalry among reigning European powers saw the entry of the Dutch, British, French, Danish among others. The fractured debilitated kingdoms of India were gradually taken over by the Europeans and indirectly controlled by puppet rulers. In 1600, Queen Elizabeth I accorded a charter, forming the East India Company to trade with India and eastern Asia. The British landed in India in Surat in 1624. By the 19th century, they had assumed direct and indirect control over most of India.

The destruction of the Amerindian population and the Atlantic slave trade

The arrival of the conquistadores caused the annihilation of most of the Amerindians. However, contemporary historians now generally reject the Black Legend according to which the brutality of the European colonists accounted for most of the deaths. It is now generally believed that diseases, such as the smallpox, brought upon by the Columbian Exchange, were the greatest destroyer, although the brutality of the conquest itself isn't contested. As late as in the 19th century, Juan Manuel de Rosas, Argentinian caudillo from 1829 to 1852, openly pursuied the extermination of the local population, an event related by Darwin in The Voyage of the Beagle (1839). He was then followed by the "Conquest of the Desert" in the 1870-80s. This slow process of extermination is still on-going: in Tierra del Fuego, there are only two natives left who speak the Yaghan language. The other Yaghans died in part of taking the European habits of wearing clothes, which proved lethal in the humid, although very cold climate. After the Amerindians' quasi-total disparition, the mines and the sugar cane plantations thus led to the booming of the Atlantic slave trade, especially apparent in the Caribbean where the largest ethnic group is of African descent.

Contemporary historians debate the legitimacy of calling the quasi-disparition of the Amerindians a "genocide". Estimates of pre-Columbian population have ranged from a low of 8.4 million to a high of 112.5 million persons; in 1976, geographer William Deneva derived a "consensus count" of about 54 million people. [3]

David Stannard has argued that "The destruction of the Indians of the Americas was, far and away, the most massive act of genocide in the history of the world", with almost 100 million Amerindians killed in what he calls the American Holocaust. Like Ward Churchill, he believes that the American natives were deliberately and systematically exterminated over the course of several centuries, and that the process continues to the present day. [4]

Stannard's claim of 100 million deaths has been disputed because he makes no distinction between death from violence and death from disease. In response, political scientist R. J. Rummel has instead estimated that over the centuries of European colonization about 2 million to 15 million American indigenous people were the victims of what he calls democide. "Even if these figures are remotely true," writes Rummel, "then this still make this subjugation of the Americas one of the bloodier, centuries long, democides in world history." [5]

Independence in the Americas

During the five decades following 1770, Britain, France, Spain and Portugal lost their most valuable colonies in the Americas.

Britain and The Thirteen Colonies

After the conclusion of the Seven Years' War in 1763, Britain had emerged as the world's dominant power, but found itself mired in debt and struggling to finance the Navy and Army necessary to maintain a global empire. The British Parliament's attempt to raise taxes on the North American colonists raised fears among the Americans that their rights as "Englishmen," particularly their rights of self-government, were in danger. A series of disputes with Parliament over taxation led first to informal committees of correspondence among the colonies, then to coordinated protest and resistance, and finally to the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, by the Second Continental Congress.

France and The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804)

The Haïtian Revolution, a slave revolt led by Toussaint L'Ouverture in the the French colony of Saint-Domingue, established Haïti as a free, black republic, the first of its kind, and the second independent nation in the Western Hemisphere after the United States. Africans and people of African ancestry freed themselves from slavery and colonization by taking advantage of the conflict among whites over how to implement the reforms of the French Revolution in this slave society. Although independence was declared in 1804, it was not until 1825 that it was formally recognised by King Charles X of France.

Spain and the Wars of Independence in Latin America

The Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821) and the various Wars of Independence led in the 1810s and 1820s by famous Libertadores such as José de San Martin in the South or Simón Bolívar in the North, brought to most Latin American countries independence from the European powers.

As in North America, the independent territories still had to be fully explored. Thus, in Argentina, caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas pursuied the "conquest of the desert" from 1829 to 1852, explicitly leading a "campaign of extermination" against the indigenous people. The Empire of Brazil, proclaimed in 1822 by Dom Pedro I, began to colonize its backcountry (including the Sertão), an enterprise which continues to this day in the Amazons. The 1888 Lei Áurea abolished slavery, creating public uproar among Brazilian slave owners and upper classes, which was the immediate cause of the toppling of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic in 1889.

The 1898 Spanish-American War, during which the United States occupied Cuba and Puerto Rico, ended Spanish occupation in the Americas.

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Portugal and Brazil

Brazil was the only country in Latin America to gain its independence without bloodshed. The invasion of Portugal by Napoleon in 1808 had forced the King Joao VI to flee to Brazil and establish his court in Rio de Janeiro. For thirteen years, Portugal was ruled from Brazil (the only instance of such a reversal of roles between colony and metropole) until his return to Portugal in 1821. His son, Dom Pedro, was left in charge of Brazil and in 1822 he declared independence from Portugal and himself the Emporer of Brazil. Unlike Spain's former colonies which had abandoned the monarchy in favour of republicanism, Brazil therefore retained its links with its monarchy, the House of Braganza.

The second European colonization wave in the 19th-20th century

The New Imperialism

The latter half of 19th century saw the transition from an "informal" empire of control through military and economic dominance to direct control, marked from the 1870s on by the scramble for territory in areas previously regarded as merely under Western influence. Colonialism would take its full extent only during the period known as New Imperialism, starting in the 1860s with the Scramble for Africa.

The Berlin Conference (1884 - 1885) mediated the imperial competition among Britain, France and Germany, defining "effective occupation" as the criterion for international recognition of colonial claims and codifying the imposition of direct rule, accomplished usually through armed force.

A decade later, rival imperialisms would collide in the 1898 Fashoda Incident, during which war between France and Britain was barely avoided. This fear led to new alliances, and in 1904 the Entente Cordiale was signed between both powers. Imperialistic rivalry between the European powers would a main cause of the triggering of World War I in 1914.

In Germany, rising pan-germanism was coupled to imperialism in the Alldeutsche Verband ("Pangermanic League"), which argued that Britain's world power position gave the British unfair advantages on international markets, thus limiting Germany's economic growth and threatening its security.

North America in the 19th century

After the American Revolution and the 1776 independence of the United States, the colonization was not quite finished. As in South America, the frontier and the Wild West had to be conquered. For the next century, the expansion of the nation into these areas, as well as the subsequently acquired Louisiana Purchase (1803), Oregon Country (1846) and Mexican Cession (1848, after the Mexican-American War), would absorb much of the energy of the nation and largely define its politics and character, in particular its relations with Native Americans. The question of whether the American frontier would become "slave" or "free" was a spark of the American Civil War (1861-1865).

The settlement of the West became progressively organized through acts of the federal government, most notably the 1862 Homestead Act. In 1890, the frontier line was no more, though the frontier still existed in disconnected locations. The popular culture impact of the frontier was enormous, in dime novels, Wild West shows, and, after 1910, Western movies set on the frontier.

The colonization wasn't anymore pacifist than it had been elsewhere. North America was also the theater of the use of detention centers, population transfers (leading to the Seminole Wars in Florida at the beginning of the 19th century) and "unvoluntary extermination" (through diseases). In the United States, the 1830 Indian Removal treaty was a policy seeking to relocate American Indian (or "Native American") tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river. In the decades following the American Revolution (1763-1783), the rapidly increasing population of the United States resulted in numerous treaties in which lands were purchased from Native Americans. Eventually, the U.S. government began encouraging Indian tribes to sell their land by offering them land in the West, outside the boundaries of the then-existing U.S. states, where the tribes could resettle. This process was accelerated with the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which provided funds for President Andrew Jackson (1829-1837) to conduct land-exchange ("removal") treaties. An estimated 100,000 American Indians eventually relocated in the West as a result of this policy, most of them emigrating during the 1830s, settling in what was known as the "Indian territory".

The first large-scale confinement of a specific ethnic group in detention centers began in the summer of 1838, when President Martin Van Buren (1837-1841) ordered the U.S. Army to enforce the December 29, 1835 Treaty of New Echota (an Indian Removal treaty) by rounding up the Cherokee into prison camps before relocating them. Although these camps were not intended to be extermination camps, and there was no official policy to kill people, some Indians were raped and/or murdered by US soldiers. Many more died in these camps due to disease, which spread rapidly because of the close quarters and bad sanitary conditions. This event, known as the Trail of Tears (or Nunna daul Isunyi - "The Trail Where We Cried" in Cherokee), resulted in the deaths of an estimated 4,000 Cherokee Indians. Throughout the remainder of the Indian Wars, various populations of Native Americans were rounded up, trekked across country and put into detention, some for as long as 27 years.

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

The Scramble for Africa

Many European statesmen and industrialists wanted to accelerate the Scramble for Africa, securing colonies before they strictly needed them. The champion of Realpolitik, Bismarck thus pushed a Weltpolitik vision ("World Politic"), which considered the colonization as a necessity for the emerging German power. German colonies in Togoland, Samoa, South-West Africa and New Guinea had corporate commercial roots, while the equivalent German-dominated areas in East Africa and China owed more to political motives. The British also took an interest in Africa, using the East Africa company to take over Kenya and Uganda. The British crown formally took over in 1895 and renamed the area the East Africa Protectorate.

Leopold II of Belgium personally owned the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908, while the Dutch had the Dutch East Indies.

In the same manner, Italy tried to conquer its "place in the sun", acquiring Somaliland in 1899-90, Eritrea and 1899, and, taking advantage of the "Sick Man of Europe", the Ottoman Empire, also conquered Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern Libya) with the 1911 Treaty of Lausanne. The conquest of Ethiopia, which had remained the last African independent territory, had to wait till the Second Italo-Abyssinian War in 1935-36 (the First Italo-Abyssinian War in 1895-96 had been a disaster for Italian troops).

The Portuguese and Spanish colonial empire were smaller, mostly legacies of past colonization. Most of their colonies had acquired independence during the Latin American revolutions at the beginning of the 19th century.

German colonialism

Imperialism in Asia

In Asia, the Great Game, which lasted from 1813 to 1907, opposed the British Empire against Imperial Russia for supremacy in Central Asia. China was opened to Western influence starting with the First and Second Opium Wars (1839-1842; 1856-1860). After the visits of Commodore Matthew Perry in 1852-1854, Japan opened itself to the Western world during the Meiji Era (1868-1912).

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

After World War I

The colonial map was redrawn following the defeat of Germany and the Ottoman Empire after the first World War (1914-18). Colonies from the defeated empires were transferred to the newly founded League of Nations, which itself redistributed it to the victorious powers as "mandates".

The twentieth century saw the era of the banana republics, in particular in Latin America, whereby corporations such as United Fruit or Standard Fruit dominated the economies and sometimes the politics of parts of Latin America. The United Fruit, nicknamed 'The Octopus' for its willingness to involve itself in politics, was present in most American countries and was involved in several coups, in Honduras and elsewhere. 1971 Nobel prize for literature winner Pablo Neruda would later denounce such neocolonialism in a poem titled La United Fruit Co.

Oil companies such as BP and Royal Dutch Shell held sway in "key" areas such as parts of Iran and of Nigeria, despite the preservation of de jure independence.

Middle East

After World War I, the Arabs, who had revolted against the Ottomans in 1916-18, supported by the UK who sent them Captain T. E. Lawrence, found they had been doubly betrayed. For not only had the British and the French concluded the secret 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement to partition the Middle East between them, but the British had also promised to the international Zionist movement their support in creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine via the 1917 Balfour Declaration, although the former site of the ancient Kingdom of Israel had had a largely Arab population for over a thousand years. When the Ottomans departed, the Arabs proclaimed an independent state in Damascus, but were too weak, militarily and economically, to resist the European powers for long, and Britain and France soon established control and re-arranged the Middle East to suit themselves.

Syria became a French protectorate (thinly disguised as a League of Nations Mandate), with the Christian coastal areas split off to become Lebanon. Iraq and Palestine became British mandated territories, with one of Sherif Hussein's sons, Faisal, installed as King of Iraq. Palestine was split in half, with the eastern half becoming Transjordan to provide a throne for another of Hussein's sons, Abdullah. The western half of Palestine was placed under direct British administration, and the already substantial Jewish population was allowed to increase, initially under British protection. Most of the Arabian peninsula fell to another British ally, Ibn Saud, who created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1922.

Another turning point in the history of the Middle East came when oil was discovered, first in Persia in 1908 and later in Saudi Arabia (in 1938) and the other Persian Gulf states, and also in Libya and Algeria. The Middle East, it turned out, possessed the world's largest easily accessible reserves of crude oil. Although Western oil companies pumped and exported nearly all of the oil to fuel the rapidly expanding automobile industry and other industrial developments, the emirs of the oil states became immensely rich, enabling them to consolidate their hold on power and giving them a stake in preserving Western hegemony over the region. Oil wealth also had the effect of stultifying whatever movement towards economic, political or social reform might have emerged in the Arab world under the influence of the Kemalist revolution , which had created the modern state of Turkey in 1923 out of the ashes of the Ottoman Empire.

During the 1920-30s Iraq, Syria and Egypt moved towards independence, although the British and French did not formally depart the region until they were forced to do so after World War II. But in Palestine the conflicting forces of Arab nationalism and Zionist colonisation created a situation which the British could neither resolve nor extricate themselves from. Although the Zionist movement was born in the 19th century, following various pogroms and the Dreyfus Affair, with Theodor Herzl's Der Judenstaat (1896), the rise of nazism created a new urgency in the quest to create a Jewish state in Palestine, and the evident intentions of the Zionists provoked increasingly fierce Arab resistance, with the Great Uprising in 1936-39.

This struggle culminated in the 1947 UN Partition Plan in favor of a Two-state solution instead of a Binational solution. The plan was rejected and the State of Israel proclaimed in 1948, leading to the first Arab-Israeli War and to the creation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. About 800,000 Palestinians fled from areas annexed by Israel, thus creating the "Palestinian problem" which has bedevilled the region ever since. The conflict also resulted in hundreads of thousands of Jews refugees who fled to Israel from Arab countries. The June 1967 Six Day War led to the occupation of various territories. In November 1967, UN Resolution 242 called for the "withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict", something which has became a permanent revendication of the Fatah, founded by Yassir Arafat in 1959, and of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) founded in 1964 by the Arab League.

Pan-Arabism was a popular anti-imperialist ideology in the 1960s, and Nasserism favorized the merging of Egypt and Syria into the United Arab Republic (1958-61). The short term Arab Federation of Iraq and Jordan (1958) also attempted to bypass the 1920s artificial borders. Pan-Arabism was however defeated with the 1967 Six-Day War and the emergence of Islamism in the 1980s as a popular substitution to secular Arab nationalism, as represented for example by the Baath Party.

Japanese imperialism

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

After being closed for centuries to Western influence, Japan opened itself to the West during the Meiji Era (1868-1912), characterized by swift modernization and borrowings from European culture (in law, science, etc.) This, in turn, helped make Japan the modern power that it is now, which was symbolized as soon as the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War: this war marked the first victory of an Asian people against a European imperial power, and led to widespread fears among European populations (first appearance of the "Yellow Peril"). During the first part of the 20th century, while China was still victim of various European imperialisms, Japan became an imperialist power, conquering what it called a "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere".

Japan's encroachment on Korea began with the 1876 Treaty of Kanghwa with the Joseon Dynasty of Korea, increased with the 1895 assassination of Empress Myeongseong and the 1905 Eulsa Treaty, and was completed with the illicit 1910 Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty. In 1910, Korea was formally annexed to the Japanese Empire. The Japanese colonization of Korea was particularly brutal, even by 20th Century standards. This brutal colonization included the use of Korean "comfort women" who were forced to serve as sex slaves in Japanese Army brothels. For additional information see Korea under Japanese rule.

In 1931 Japanese army units based in Manchuria seized control of the region; full-scale war with China followed in 1937, drawing Japan toward an overambitious bid for Asian hegemony (Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere), which ultimately led to defeat and the loss of all its overseas territories after World War II (see Japanese expansionism and Japanese nationalism). As in Korea, the Japanese treatment of the Chinese people was particularly brutal as exemplified by the Nanjing Massacre.

The French colonial empire

In France, the colonial empire was not used for massive emigration, as in the British Empire. In fact, until the Third Republic (1871-1940), apart from the colonization of Algeria started on June 12, 1830, in the last days of the Restoration, France did not have yet many colonies compared to the Spanish or the Portuguese empire. The Antilles, in the Caribbean Sea, had been colonized during this first wave of colonialism. After the repression of the 1871 Paris Commune, the French Guiana — as well as New Caledonia — were used for transportation of criminals and Communards. Because of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the "colonial lobby", gathering a few politicians, businessmen and geographers favorable to colonialism, was not very popular until World War I. In the 1880s, a debate thus opposed those who opposed colonization, such as Georges Clemenceau (Radical), who declared that colonialism diverted France from the "blue line of the Vosges", referring to the disputed Alsace-Lorraine region, Jean Jaurès (Socialist) or Maurice Barrès (nationalist), to the "colonial lobby", supported by Jules Ferry (moderate republican), Léon Gambetta (republican) or Eugène Etienne, the president of the parliamentary colonial group.

Prime minister from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885, Republican Jules Ferry directed the negotiations which led to the establishment of a French protectorate in Tunis (1881) (the Bardo treaty), prepared the treaty of December 17, 1885 for the occupation of Madagascar; directed the exploration of the Congo and of the Niger region; and above all he organized the conquest of Indochina. The excitement caused at Paris by the sudden retreat of the French troops from Lang Son led to his violent denunciation by Clemenceau and other radicals, and his downfall on March 30, 1885. Although the treaty of peace with China (June 9, 1885), in which the Qing Dynasty ceded suzerainty of Annam and Tonkin to France, was the work of his ministry, he would never again serve as premiere.

According to Sandrine Lemaire, only 1% of the French population actually visited its colonial empire. Because of this relative unpopularity, until at least World War I, the colonial lobby set up an intensive propaganda campaign in order to convince the French of the legitimacy of its Empire, which most thought costly and rather useless. Ethnological expositions — including human zoos, in which natives were displayed alongside apes, in an attempt to justify scientific racism and to popularize the colonial empire — had a crucial role in the popularisation of colonialism [6]. Although in France these colonial exhibitions played a crucial propaganda role, they were common in all colonizing powers: the 1924 British Empire Exhibition was one notable example, as was the successful 1931 Exposition coloniale in Paris. Germany and Portugal also had such exhibitions, as well as Belgium's, which had a Foire coloniale as late as 1948. The political scientist Pierre-André Taguieff said about the French Third Republic that it was host to "racialism or an ideological racism that didn't perceive itself as such, and that called neither for hate, nor for stigmatisation, nor either for segregation, but which found its legitimity in colonial exploitation and domination, and its justification in its thesis of the future evolution of these inferior peoples".

Olivier LeCour Grandmaison has argued, for his part, that the techniques used for the French colonization of Algeria starting with the invasion on June 12, 1830, a few days before the end of the Restoration, were later extended to the whole of the French colonial empire (Indochina, New Caledonia, French West Africa, a federation created in 1895, and French Equatorial Africa, created in 1910). LeCour Grandmaison argued that Algeria thus provided the laboratory for concepts later used during the Holocaust, such as "inferior races", "life without value" — Lebensunwertes Leben — and "vital space" (translated in German by "Lebensraum", a concept used by the Völkisch movement), as well as for repressive techniques: the 1881 Indigenous Code in Algeria, the principle of "collective responsibility", the "Scorched Earth" policy, which made of French colonial rule in Algeria a permanent state of exception. Internment camps were also first tested during the 1830 invasion of Algeria, before being used (under the official name of concentration camps) to receive the Spanish Republican refugees first, than to intern communists and, finally, Jews during Vichy France [7]. Concentration camps were also used by the British Empire during the Second Boer War (1899-1902).

After World War I, the colonized people were frustrated at France's failure to recognize the effort provided by the French colonies (resources, but more importantly colonial troops - the famous tirailleurs). Although in Paris the Great Mosque of Paris was constructed as recognition of these efforts, the French state had no intention to allow self-rule, let alone independence to the colonized people. Thus, nationalism in the colonies became stronger in between the two wars, leading to Abd el-Krim's Rif War in Morocco and to the creation of Messali Hadj's Star of North Africa in Algeria. However, these movements would gain full potential only after World War II. The October 27, 1946 Constitution creating the Fourth Republic substituted the French Union to the colonial empire. On the night of March 29, 1947, a nationalist uprising in Madagascar led the French government led by Paul Ramadier (Socialist) to violent repression: one year of bitter fighting, in which 90,000 to 100,000 Malagasy died. On May 8, 1945, the Setif massacre took place in Algeria.

In 1946, the states of French Indochina withdrew from the Union, leading to the Indochina War (1946-54). In 1956, Morocco and Tunisia gained their independence, while the Algerian War was raging (1954-1962). With Charles de Gaulle's return to power in 1958 amidst turmoil and threats of a right-wing coup d'Etat to protect "French Algeria", the decolonization was completed with the independence of African's colonies in 1960 and the March 19, 1962 Evian Accords, which put an end to the Algerian war. To this day, the Algerian war — officially called until the 1990s a "public order operation" — remains a traumatism both for France and Algeria. Philosopher Paul Ricœur has spoke of the necessity of a "decolonization of memory", starting with the recognition of the 1961 Paris massacre during the Algerian war and the recognition of the decisive role of immigrated manpower in the Trente Glorieuses post-WW II economic growth period. In the 1960s, due to the necessity of reconstruction and of economic growth, French employers actively sought manpower in the colonies, explaining today's multiethnic population. The February 23, 2005 law on colonialism voted by the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) conservative majority was finally repealed by president Jacques Chirac (UMP) start of 2006.

Decolonization