Décolletage: Difference between revisions

m added a space between sentences. Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit |

m removed extra space inside of resurged Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

The low or plunging necklines style emphasizes womens chest. Fashion trends like these direct the eyes so they focus on specific female body parts. These revealing dressed which were cut to display woman's cleavage are often seen on celebrities attending red carpet events. There these gowns are generally recognized as elegant and sensual. Low cut trend is frequently seen in evening wear dresses. Fashion uses cleavage representing femininity and sexuality in women's clothing.<ref name="dress">{{cite journal |last1=Reynolds |first1=Sarah |title="Boobs Out! A Perspective on Fashion, Sexuality and Equality" |journal=Art and Design Review |date=22 May 2017 |volume= 5 |issue= 2 |pages=116–124|doi=10.4236/adr.2017.52009}}</ref> |

The low or plunging necklines style emphasizes womens chest. Fashion trends like these direct the eyes so they focus on specific female body parts. These revealing dressed which were cut to display woman's cleavage are often seen on celebrities attending red carpet events. There these gowns are generally recognized as elegant and sensual. Low cut trend is frequently seen in evening wear dresses. Fashion uses cleavage representing femininity and sexuality in women's clothing.<ref name="dress">{{cite journal |last1=Reynolds |first1=Sarah |title="Boobs Out! A Perspective on Fashion, Sexuality and Equality" |journal=Art and Design Review |date=22 May 2017 |volume= 5 |issue= 2 |pages=116–124|doi=10.4236/adr.2017.52009}}</ref> |

||

Gowns featuring low or plunging neckline are popular in western culture. The Victorian Era dresses featured low neckline style. Modern gowns featuring these styles draw from historical periods such as the Victorian Era. Modern dresses featuring lower cut or plunging necklines have |

Gowns featuring low or plunging neckline are popular in western culture. The Victorian Era dresses featured low neckline style. Modern gowns featuring these styles draw from historical periods such as the Victorian Era. Modern dresses featuring lower cut or plunging necklines have resurged considerable at exclusive social events. Low and plunging neckline gowns have appeared on several red carpet events recently including the 2017 Golden Globes.<ref name="dress" /> |

||

The dresses of this kind use the sexual aesthetic of female breast. Fashions such as these highlight erogenous zone that western societies have typically been attracted to. The revealing modern fashions can be linked to histories of breast fetishism in the west. Breast fetishism insist that women’s chest are objects of sexual desire. Breast manipulation in women's dress was visible in the 16th and 17th centuries with another trend - corsets. This form of fetishism in fashion became popular again in the 40's and 50's after World War II.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kunzle |first1=David |title=Fashion and Fetishism: Corsets, Tight-Lacing & Other Forms of Body-Sculpture |date=2013 |publisher=The History Press |isbn=978 0 7524 9545 3 |edition= ebook |accessdate= 16 May 2019|url= https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=LwE_DQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT16&dq=breast+fetishism&ots=mNw4bqadFO&sig=BeNlMjCs7kQgFSQB8q77x7GEKaU#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> Historically, there has been an argument that the women’s exposed body parts are distracting to the opposite gender. This notion is now being used by feminist to place power into women’s hands. There are now cases where women will purposely use their distracting clothing such as low cut and plunging necklines to acquire power in spaces they have not traditional had it.<ref name="dress" /> |

The dresses of this kind use the sexual aesthetic of female breast. Fashions such as these highlight erogenous zone that western societies have typically been attracted to. The revealing modern fashions can be linked to histories of breast fetishism in the west. Breast fetishism insist that women’s chest are objects of sexual desire. Breast manipulation in women's dress was visible in the 16th and 17th centuries with another trend - corsets. This form of fetishism in fashion became popular again in the 40's and 50's after World War II.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kunzle |first1=David |title=Fashion and Fetishism: Corsets, Tight-Lacing & Other Forms of Body-Sculpture |date=2013 |publisher=The History Press |isbn=978 0 7524 9545 3 |edition= ebook |accessdate= 16 May 2019|url= https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=LwE_DQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT16&dq=breast+fetishism&ots=mNw4bqadFO&sig=BeNlMjCs7kQgFSQB8q77x7GEKaU#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> Historically, there has been an argument that the women’s exposed body parts are distracting to the opposite gender. This notion is now being used by feminist to place power into women’s hands. There are now cases where women will purposely use their distracting clothing such as low cut and plunging necklines to acquire power in spaces they have not traditional had it.<ref name="dress" /> |

||

Revision as of 22:19, 12 June 2019

Décolletage /dɪˈkɒlətɑːʒ/ (or décolleté, its adjectival form, in current French) is a term used in woman's fashion referring to the upper part of a woman's torso, comprising her neck, shoulders, back and upper chest, that is exposed by the neckline of her clothing. The term is most commonly used in Western female fashions and is most commonly applied to a neckline that reveals or emphasizes cleavage. Low-cut necklines are a feature of ball gowns, evening gowns, leotards, lingerie and swimsuits, among other fashions. Although décolletage does not itself prescribe the extent of exposure of a woman's upper chest, the design of a décolleté garment takes into account current fashions, aesthetics, social norms and the occasion when a garment will be worn.

Though neckline styles have varied in Western societies and décolletage may be regarded as aesthetic and an expression of femininity, in some parts of the world any décolletage is considered provocative and shocking.

Etymology

Décolletage is a French word which is derived from décolleter, meaning to reveal the neck.[1] The term was first used in English literature sometime before 1831.[2] In strict usage, décolletage is the neckline extending about two handbreadths from the base of the neck down, front and back.[3]

History

In Indonesia (especially in Java), a breast cloth known as kemben was worn for centuries until the 20th century. Today, shoulder-exposing gowns still feature in many Indonesian rituals.

Gowns which exposed a woman's neck and top of her chest were very common and non-controversial in Europe from at least the 11th century until the Victorian period in the 19th century. Ball or evening gowns especially featured low square décolletage designed to display and emphasize cleavage.[4][5] During that long period, low-cut dresses partially exposing breasts were considered more acceptable than they are today; a woman's bared legs, ankles, or shoulders were considered more risqué than exposed breasts.[6]

In 1450, Agnès Sorel, mistress to Charles VII of France, is credited with starting a fashion when she wore deep low square décolleté gowns with fully bared breasts in the French court.[7] Other aristocratic women of the time who were painted with breasts exposed included Simonetta Vespucci, whose portrait with exposed breasts was painted by Piero di Cosimo in c. 1480.

Based on woodcut prints, a researcher has argued that during the 17th century, women's fashions with exposed breasts were common in society, from queens to common prostitutes, and emulated by all classes.[8] Anne of Brittany has also been painted wearing a dress with a square neckline. Low square décolleté styles were popular in England in the 17th century and even Queen Mary II and Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I of England, were depicted with fully bared breasts; and architect Inigo Jones designed a masque costume for Henrietta Maria that fully revealed both of her breasts.[8][9]

In aristocratic and upper-class circles, the display of breasts was at times regarded as a status symbol, as a sign of beauty, wealth or social position.[10] From the Renaissance onwards, the bared breast even invoked associations with nude sculptures of classical Greece that were exerting an influence on art, sculpture, and architecture of the period.[9]

After the French Revolution décolletage become larger in the front and less in the back.[11] During the fashions of the period 1795–1820, many women wore dresses which bared the bosom and shoulders. James Gillray's caricature of 1796 shows Lady Georgiana Gordon (1781–1853, so then 15 or 16), not yet Duchess of Bedford, at a rout-party gambling at a game called "Pope Joan".[12] She is wearing an extreme décolletage, as was fashionable.

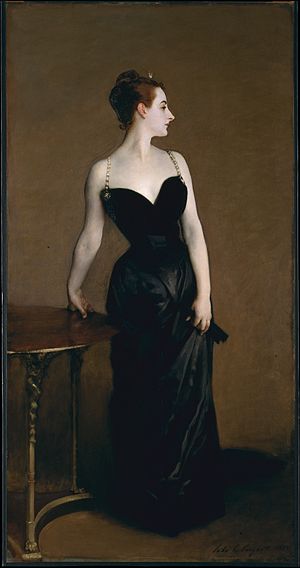

During the Victorian period, social attitudes required women to cover their bosom in public. For ordinary wear, high collars were the norm. Towards the end of the Victorian period (end of the 19th century), the full collar was the fashion, though some décolleté dresses were worn on formal occasions. (See 1880s in fashion.) In 1884, a portrait painting by John Singer Sargent of American-born Paris socialite, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, was criticised[13] when she was depicted in a sleek black dress displaying what was considered scandalous cleavage and her right shoulder strap fallen off her shoulder. The controversy was so great that he reworked the painting to move the shoulder strap from her upper arm to her shoulder, and Sargent left Paris for London in 1884, his reputation in tatters. The painting was named "Portrait of Madame X".[14][15]

When it became fashionable, around 1913, for dresses to be worn with what would now be considered a relatively modest round or V-shaped neckline, clergymen all over the world became deeply shocked. In the German Empire, all of the Roman Catholic bishops joined in issuing a pastoral letter attacking modern fashions.[16] Fashions became more restrained in terms of décolletage, while exposure of the leg became more permitted in Western societies, during World War I and remained so for nearly half a century.[17]

In 1953, Hollywood film The French Line was found objectionable under the strict Hays Code with some of Jane Russell's décolletage gowns being described as "intentionally designed to give a bosom peep-show effect beyond even extreme décolletage".[18] But other actresses defied the then standards. For example, Gina Lollobrigida raised eyebrows with her famous low-cut dress in 1960, and other celebrities, performers and models followed suit, and the public was not far behind. Low-cut styles of various depths are now common in many situations.

During a short period in 1964, "topless" dress designs appeared at fashion shows, but those who wore the dresses in public found themselves arrested on indecency charges.[19]

Low necklines usually result in increased décolletage. In Western and some other societies, there are differences of opinion as to how much body, and especially breast, exposure is acceptable in public.[20] What is considered the appropriate neckline varies by context, and is open to differences of opinion. In the United States, in two separate incidents in 2007, Southwest Airlines crews asked travelers to modify their clothing, to wear sweaters, or to leave the plane because the crew did not consider the amount of cleavage displayed acceptable.[21] German Chancellor Angela Merkel created controversy when she wore a low-cut evening gown to the opening of the Oslo Opera House in 2008.[22] In the 2010s, fashion which covered more of women's bodies became more popular, including higher or crew-cut necklines.[23]

Low Neckline/Plunging Neckline Gowns

The low or plunging necklines style emphasizes womens chest. Fashion trends like these direct the eyes so they focus on specific female body parts. These revealing dressed which were cut to display woman's cleavage are often seen on celebrities attending red carpet events. There these gowns are generally recognized as elegant and sensual. Low cut trend is frequently seen in evening wear dresses. Fashion uses cleavage representing femininity and sexuality in women's clothing.[24]

Gowns featuring low or plunging neckline are popular in western culture. The Victorian Era dresses featured low neckline style. Modern gowns featuring these styles draw from historical periods such as the Victorian Era. Modern dresses featuring lower cut or plunging necklines have resurged considerable at exclusive social events. Low and plunging neckline gowns have appeared on several red carpet events recently including the 2017 Golden Globes.[24]

The dresses of this kind use the sexual aesthetic of female breast. Fashions such as these highlight erogenous zone that western societies have typically been attracted to. The revealing modern fashions can be linked to histories of breast fetishism in the west. Breast fetishism insist that women’s chest are objects of sexual desire. Breast manipulation in women's dress was visible in the 16th and 17th centuries with another trend - corsets. This form of fetishism in fashion became popular again in the 40's and 50's after World War II.[25] Historically, there has been an argument that the women’s exposed body parts are distracting to the opposite gender. This notion is now being used by feminist to place power into women’s hands. There are now cases where women will purposely use their distracting clothing such as low cut and plunging necklines to acquire power in spaces they have not traditional had it.[24]

See also

References

- ^ The Free Dictionary

- ^ Barnhart, Robert K., ed. (1994). Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-270084-1.

- ^ Rudofsky, Bernard (1984). The Unfashionable Human Body (Repr. d. Ausg. ed.). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co. ISBN 978-0-442-27636-2.

- ^ Gernsheim, pp. 25–26, 43, 53, 63.

- ^ Desmond Morris (2004). The Naked Woman. A Study of the Female Body, p. 156. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0-312-33853-8.

- ^ C. Willett; Phillis Cunnington (1981). The History of Underclothes. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-486-27124-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Monique Canellas-Zimmer (2005). Histoires de mode, Les Dossiers d'Aquitaine. ISBN 978-2846221191.

- ^ a b "Historian Reveals Janet Jackson's 'Accidental' Exposing of Her Breast was the Height of Fashion in the 1600s". University of Warwick. 5 May 2004. Archived from the original on 3 August 2004.

- ^ a b Lucy Gent and Nigel Llewellyn, eds. (1990). Renaissance Bodies: The Human Figure in English Culture c. 1540–1660. London: Reaktion Books.

- ^ "French Caricature". University of Virginia Health System. Archived from the original on 2010-06-01. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ S. Devadas Pillai (1997). Indian Sociology through Ghurye, A Dictionary, p. 68, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-807-5.

- ^ In Georgian England a "rout" or "rout-party" was a relatively informal party given by the well-off, to which large numbers of people were invited. The term covered a variety of styles of event, but they tended to be basic, and a guest could not count on any music, food, drink and dancing being available, though any of these might be.

- ^ Richard Ormand and Elaine Kilmurray (1980). Sargent: The Early Portraits, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 114, ISBN 0-300-07245-7

- ^ Fairbrother, Trevor (2001). John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist. p. 139, Note 4. ISBN 978-0-300-08744-4.

- ^ "Sargent's Portraits", an article including a mention of the scandal caused by the portrayal of cleavage in John Singer Sargent's "Portrait of Madame X".

- ^ Gernsheim, 94.

- ^ Kim K.P., Johnson, Susan J. Torntore, and Joanne Bubolz Eicher (2003). Fashion foundations, p. 716, Berg Publishers. ISBN 1-85973-619-X.

- ^ Doherty, Thomas (2007). Hollywood's Censor: Joseph I. Breen and the Production Code Administration. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14358-5.

- ^ "Sixties City – Bringing on back the good times". Archived from the original on 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Salmansohn, Karen. "The Power of Cleavage". The Huffington Post, October 29, 2007.

- ^ NBC News. "Woman told she was too Hot to Fly"

- ^ "Merkel 'Surprised' by Attention to Low-cut Dress". Spiegel Online. 15 April 2008.

- ^ Friedman, Vanessa (6 April 2017). "Women, Fashion Has You Covered". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, Sarah (22 May 2017). ""Boobs Out! A Perspective on Fashion, Sexuality and Equality"". Art and Design Review. 5 (2): 116–124. doi:10.4236/adr.2017.52009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kunzle, David (2013). Fashion and Fetishism: Corsets, Tight-Lacing & Other Forms of Body-Sculpture (ebook ed.). The History Press. ISBN 978 0 7524 9545 3. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Alison Gernsheim (1981 [1963]). Victorian and Edwardian Fashion. A Photographic Survey. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-24205-6

Further reading

- Desmond Morris (1997). Manwatching. A Field Guide to Human Behavior. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-1310-0