Frankenstein, the Baroness, and the Climate Refugees of 1816

It is two hundred years since "The Year Without a Summer", when a sun-obscuring ash cloud — ejected from one of the most powerful volcanic eruptions in recorded history — caused temperatures to plummet the world over. Gillen D’Arcy Wood looks at the humanitarian crisis triggered by the unusual weather, and how it offers an alternative lens through which to read Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, a book begun in its midst.

June 15, 2016

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Detail from a hand-colored engraving of Byron’s Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva, by Edward Francis Finden, ca. 1833, after a drawing by William Purser — Source.

Deep in our cultural memory, in trace form, lies the bleak image of a summer two hundred years ago in which the sun never shone, frosts cruelled crops in the fields, and our ancestors, from Europe to North America to Asia, went without bread, rice, or whatever staple food they depended upon for survival. Perhaps they died of famine or fever, or became refugees. More likely, no record remains of what they suffered, except a faintly recalled reference in the tattered Rolodex of our minds. The year 1816 has, for generations, been known as “The Year Without a Summer”: the coldest, wettest, weirdest summer of the last millennium. If you read Frankenstein at school, you probably heard some version of the literary mythology behind that year. Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley), having eloped with her poet-lover Percy Shelley, joins Lord Byron on the shores of Lake Geneva for a summer of love, boating, and Alpine picnics. But the terrible weather forces them inside. They take drugs and fornicate. They grow bored, then kinkily inventive. A ghost story competition is suggested. And boom! Mary Shelley writes Frankenstein.

Given this terrific story behind “The Year Without a Summer”, how strange that interpretations of Shelley’s novel almost entirely avoid the subject of 1816’s extreme weather. Call it English Department climate denial. More tellingly, our too-easy version of Frankenstein — oh, it’s all about technology and scientific hubris, or about industrialization — ignores completely the humanitarian climate disaster unfolding around Mary Shelley as she began drafting the novel. Starving, skeletal climate refugees in the tens of thousands roamed the highways of Europe, within a few miles of where she and her ego-charged friends were driving each other to literary distraction. Moreover, landlocked Alpine Switzerland was the worst hit region in all of Europe, producing scenes of social-ecological breakdown rarely witnessed since the hellscape of the Black Death.

Shelley’s miserable Creature, in the context of the 1816 worldwide climate shock, appears less like a symbol of technological overreach than a figure for the despised and desperate refugees crowding Switzerland’s market towns that year. Eyewitness accounts frequently refer to how hunger and persecution “turned men into beasts”, how fear of famine and disease-carrying refugees drove middle-class citizens to demonize these suffering masses as subhuman parasites, and turn them away in horror and disgust. Two hundred years on, in a summer of more record temperatures, and worldwide droughts, when refugees once again stream across the borders of German-speaking Europe, can we really afford to ignore this reading of Frankenstein as a climate change novel? The novel is a cultural treasure, but it doesn’t belong behind a glass case. It’s alive, like the monster itself. It’s on the loose in our world and our minds, stoking our darkest terrors. Shelley’s untameable tale of human pathos, suffering, and destruction is headline news: on the TV and internet, in a million images, filling well-fed, well-housed citizens with horror.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Weymouth Bay With Approaching Storm by John Constable, 1818–19 — Source.

“The Year Without a Summer” is actually a misnomer. It criminally understates the agricultural calamity that engulfed Europe, North America, and the globe for three full years after the monster eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in April 1815 spun a veil of volcanic dust around the Earth, blocking the sun. “Years Without a Summer” is at least more accurate, if not exactly hard-hitting as world-historical headlines go. 1816, 1817, and 1818. Three years of a global climate system gone haywire; floods and drought; storm tracks re-routed; ocean currents gone rogue; ruined crops; rampant disease; and a dull, meagre sun that seemed ready to fizzle out any moment. Historically speaking, the climate crisis was a “perfect storm” for Europe. It could not have come at a worse time. Twenty years of Napoleonic warfare had only just concluded on the bloody field of Waterloo. Economies were drained, trade relations in chaos, and now millions of demobilized soldiers were returning home, needing to be fed and put to work. A death toll is difficult to calculate for this immediate post-Waterloo period, but certainly tens of thousands perished from starvation and disease across Europe and the transatlantic zone, and perhaps a million worldwide.

The experiences of Shelley’s Creature in the novel make for an unforgettable psychological account of what it meant to be an environmental refugee in that period: full of fear, consumed with rage and despair, racked with hunger, empty with loneliness. That said, Shelley renders the 1816 climate crisis in implicit, symbolic form, leading us to wonder what Switzerland (and Europe) was really like that year and the two years following. Of the many accounts that survive, none is more compelling, or resonant with Shelley’s novel, than the extraordinary history of the Baroness de Krüdener.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Portrait of Baroness de Krüdener, as she was in 1820, featured in The Life and Letters of Madame de Krudener (1893), by Clarence Ford — Source.

The so-called “Lady of the Holy Alliance”, Krüdener was born in Livonia, married a Baron, wrote a popular romance novel called Valerie, then, after her religious conversion, became a close confidante of Czar Alexander during the post-Waterloo negotiations between the victorious allies. By the summer of 1816, this remarkable person had transformed herself from a giddy socialite into the leader of a travelling millennialist cult, and public enemy of Swiss authorities. She fueled her popularity through end-of-the-world sermonizing and munificent handouts to the starving refugees who followed her in droves.

A reverent memoir of the Baroness de Krüdener was published in 1849. It contains excerpts from her private and public letters, and includes eyewitness accounts of her two-year ministry to the climate refugee hordes of France, Switzerland, and Germany along the banks of the Rhine near Basel. This was a key traversal point for refugees heading west along the river toward the port of Rotterdam, hoping for passage to North America — also for those who, unable to pay for passage, had been expelled from Holland, and were now enduring the unimaginable horror of a return journey to their abandoned villages. Looking at the Swiss map, the following scenes from Baroness de Krüdener’s one-woman humanitarian aid crusade took place barely a hundred and fifty miles from where our young Romantic tourists passed their sorry summer trading horror stories around the fireplace at the Villa Diodati by Lake Geneva. The relationship between the Baroness de Krüdener memoir and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is more than uncanny, it’s ecological. Both are testaments of the direful times.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

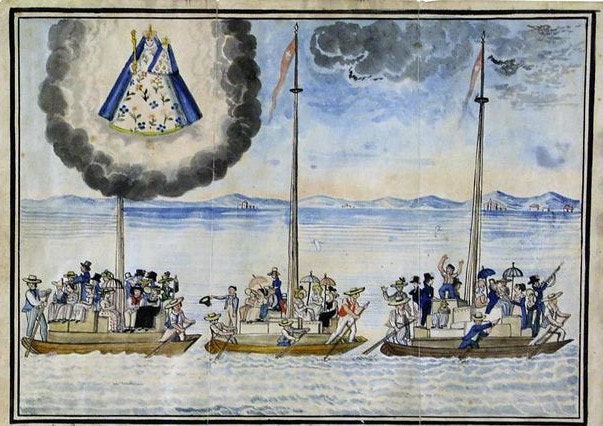

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Votive painting from 1819 depicting emigrants from Fribourg on Lake Neuchâtel on their way to Brazil via Holland as part of the 1816–17 migrations — Source.

June 1, 1816. Baroness de Krüdener has been drawing large crowds in Basel. Women, young and old, have been drawn to her example of piety, while the city fills with beggars, for whom she runs a sort of travelling soup kitchen. Fearful of her popularity and her rabble-rousing, apocalyptic message, the Basel authorities expel the Baroness from the town. She is once again homeless and without funds. But God will provide. Money flows to her from wealthy admirers, and a friend offers her a small house above the banks of the Rhine, called Hoernlein. There, on the morning of June 1, she opens her bedroom window to admire the picturesque view, only to be confronted by the soul-crushing spectacle of a refugee mass in rags, in a mile-long column, stretching from the town of Grenzach to her door.

Three months of bad weather has reduced the countryside to misery and chaos. The rain never stops beating down. The wheat rots in the fields, so too the grapes on the vine. A loaf of bread costs ten sous. The Grand Duke of Baden, the German territory north of Basel, has ordered public prayers, twice daily, in every church of the kingdom. Anxiety is everywhere. Panic builds. The refugee numbers in the fields outside Basel grow day by day, from the hundreds to the thousands.

Enemies of the Baroness infiltrate the crowd, mocking her with blasphemies while she preaches. The Basel police, too, have followed her. Sometimes they surround the house to keep the refugees at bay. Other times, they beat them furiously with their swords and drive them away into the fields and the forest. “Marche! Marche!” they yell. For the authorities of Basel, the greatest fear is that this army of beggars, having camped here, might stay and further deplete their own grain stocks.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

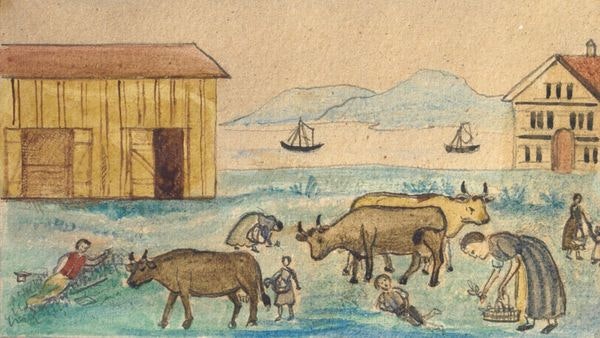

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Depiction of people eating grass due to hunger, most likely during the 1816–17 famine in Switzerland. Artist unknown though likely to be Swiss artist Anna Barbara Giezendanner (1831–1905) — Source.

As winter approaches, the Baroness sells the jewels and fine clothes from her previous life as a salon belle to raise money: thirty thousand francs, all to feed the poor at her door, who now number four thousand a day. “If you only knew how my life is,” she writes to a friend, “the hundreds of suffering, miserable beings who cling to me: misery, misfortune, despair in a thousand forms, in a land of ruin and desolation.” Pale, skinny children and exhausted women, bereft even of clothing necessary to preserve modesty, pass under the windows of Baroness de Krüdener. Their fellow citizens look upon these refugees with hatred, afraid that a growing population will drive the price of bread in the region still higher, and drag them all into the black hole of famine. For this, they blame the Baroness, who is harassed by local thugs, and condemned in the newspapers. They call her “Devil Woman”.

The new harvest has failed utterly, and now even the tradesmen and merchants in the towns are feeling the pinch of food shortages, on the brink of winter. Day after day, the starving poor come from miles around to Baroness de Krüdener’s little house on the Rhine for a ration of soup. In the heart of this worst of winters, the Baroness writes an open letter to Baron Berckheim, Interior Minister of nearby Carlsruhe, who has viciously attacked her in the press, impugning her motives and Christian sincerity: “If only you knew, Monsieur,” she writes in her indignant reply,

the calamities that have destroyed these lands, you would easily understand my situation. Judge for yourself: ask yourself if in this desolate time, when thousands wander from place to place without work or food, when mothers exhausted by hunger and sorrow come to me, laying their pitiable children at my feet, and confess their temptation, in the depths of their despair, to drown them in the Rhine, ask yourself, should I refuse them shelter? . . . I well understand that governments are powerless in this time of distress. But to answer your charges against me, when the Rhine is clogged with corpses, the Black Forest echoes with the cries of the needy, and the cantons of Switzerland are ravaged by famine, I need only appeal to the tribunal of the Lord, whose authority is far greater than yours.

As the winter of 1816–17 lapses into another cold, wet spring, the Baroness de Krüdener has spent a total of 120,000 francs in feeding an estimated 25,000 refugees, climate victims who would otherwise have died of hunger and cold. These desperate poor come from far beyond the Basel region, drawn by rumors of her largesse. Then, unbelievably, conditions worsen. It snows the entire month of April 1817, the harvest fails again, and all Switzerland teeters on the brink of collapse. The desperation on the faces of the refugees turns to a kind of dumb, inhuman stupor. From four in the morning, before the sun has risen, their groans and cries of hunger wake the Baroness from her bed. To the kitchen she goes in the darkness, where her small band of devoted followers is already preparing soup for another day in Hell.

But by the summer of 1817, the burghers of Basel have had enough of the messianic posturings of the Baroness de Krüdener. She is ejected from Hoernlein, and escorted by police to the border. Word of the Baroness’s movements travels ahead of her. No one will take her and her refugees. In the town of Rheinfeld, her carriage is surrounded by armed townsfolk. She and her entourage face certain massacre but for the intervention of the police. It is the same at Moehlin, where only sanctuary in the house of the local priest rescues her from being stoned to death. In Zurich, the newspapers report that a young girl — in a waking trance — has foretold the imminent arrival of the Baroness de Krüdener, to be announced by a terrible storm. Once in Zurich, she draws massive crowds to hear her speak, and all are struck by “the living spirit in her words, her intimate knowledge of the human heart, and, most of all, by the irresistible charity in the tone of her voice and exhortations.”

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Watercolour by Hieronymus Hess depicting Baroness de Krüdener (in the doorway, with bonnet) greeting crowds in Grenzach-Wyhlen, near Basel — Source.

So, a celebrity evangelist is in the town. But outside of town, in the exposed and devastated countryside, horrors continue to mount, and the Baroness rejoins the epic human struggle for survival there. The summer of 1817, it turns out, is more dire even than 1816. A faithful remnant of seven hundred refugees follows the Baroness on her wandering route east. Every day, she provides each of them with a bowl for their subsistence ration. It’s a wrenching spectacle to see the voracity with which they consume their meager portion of soup. Hunger is their only thought, their sole preoccupation. Every natural sentiment has been extinguished. Even familial bonds are broken. One day a woman, having received her ration, snatches her child’s portion from his mouth and eats it herself. The same day, while the Baroness and her companions are at table eating their own frugal meal, a hideous apparition appears at the door. It is a young girl, reduced to a skeleton. Famine has caused her hair to fall out, and her belly is prodigiously swollen. She throws herself under the table to lick up crumbs, as if unaware of the people around her. The Baroness seizes hold of the child, and questions her. But the starving girl is not capable of speech, only a raucous, guttural sound. Hunger is her only language.

By this time, in the canton of Appenzell, where the Baroness now finds herself, thirty or more die every day of hunger, victims of western Europe’s last ever famine. Beggars who venture outside their villages are assaulted with sticks. Those who try to help them are threatened and fined. The starving poor are reduced to dying in their homes alone. The Baroness, on the road through Saint Gall, comes upon a refugee tide stretching as far as the eye can see, four thousand at least in number. They stagger across the muddy fields, scrounging for grass and roots to stuff into their mouths, or picking at the carcasses of long-devoured dead animals. Dysentery, the famine’s accomplice, devastates their ranks. The death toll spikes again. The Baroness continues to preach wherever she goes: “Turn to God. Time is short. Death and famine ravage the land. Be warned, I beg you!” At last, in October, in Fribourg, the road ends for the Baroness de Krüdener. The authorities break up her entourage and repatriate her to Russia. Her two-year-long humanitarian aid train, her remarkable ministry to the suffering masses of central Europe in the “Years Without a Summer”, ends with a whimper.

Scenes from the suffering world in extremis of Juliane de Krüdener in 1816 and 1817 are drawn from the same disaster landscape as Shelley’s Frankenstein. For this human tragedy that they witnessed in different degrees first hand, both the Baroness de Krüdener and Mary Shelley exhibit their own forms of creative sympathy. Frankenstein, no less than the soup kitchen at Hoernlein House, is a humanitarian composition.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

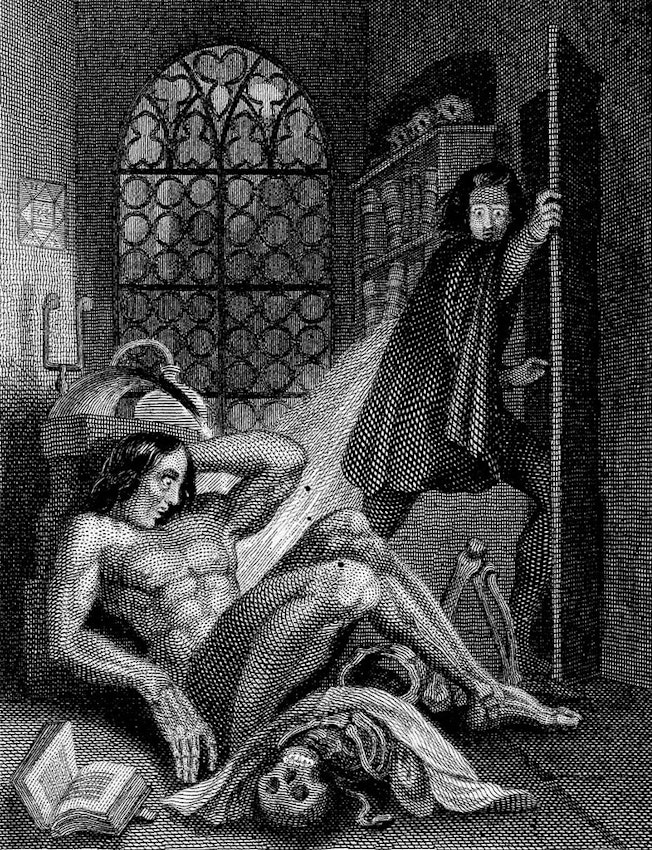

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Frankenstein observing the first stirrings of his creature. Engraving by W. Chevalier after Th. von Holst, 1831. Featured as frontispiece to the 1831 edition of Shelley’s novel Source: Wellcome Library.

Like the hordes of refugees following the Baroness de Krüdener in 1816–17, Shelley’s Creature, when he ventures into the towns, is met with fear and hostility, while the privileged families of the novel, the De Lacys and the Frankensteins — like Krüdener’s burghers of Basel — look upon him with horror and abomination. The experience of Mary Shelley’s Creature embodies the degradation and suffering of the homeless European poor in the Tambora period; the violent disgust of Frankenstein and everyone else toward him mirrors the utter want of sympathy shown by bourgeois Europeans toward Tambora’s peasant army of climate victims suffering hunger, disease, and the loss of their homes and livelihoods. As the Creature himself puts it, he suffered first “from the inclemency of the season”, but “still more from the barbarity of man”.

The summer of 2016 marks the 200th anniversary of Mary Shelley’s first sitting down to write Frankenstein, one of the great cultural artifacts of modernity. It’s the bicentenary, too, of the so-called “Year Without a Summer”, which impacted her writing of the novel more than we ever guessed. In her masterpiece of science fiction-cum-disaster journalism, Shelley connected herself, psychologically, to the experience of the starving and diseased thousands in the neighbouring countryside, climate victims who never enjoyed proper representation in the press and parliaments of Europe but mostly sank into oblivion, unmourned. In Frankenstein’s Creature, Mary Shelley offers us the most powerful possible incarnation of the loathed and dehumanized refugee. The “Year Without a Summer”, with its ghost story competition by the lake, remains one of the best-loved biographical vignettes of the Romantic period. But now, as we commemorate that direful year, it is no longer the story it was. With drastic climate change as context, and by adding the likes of the Baroness de Krüdener to its celebrity cast list, we unveil a true myth still grander, more totemic, and more urgent. The monster is back. He’s on the loose. And because we are all of us Doctor Frankensteins, this rampant Creature, full of rage and hurt, is our responsibility now.

Gillen D’Arcy Wood was born in Ballarat, Australia, and received his Ph.D from Columbia University in 2000. He is currently Professor of English at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. He is the author of two books on British Romanticism: The Shock of the Real: Romanticism and Visual Culture (Palgrave, 2001) and Romanticism and Music Culture in Britain, 1780-1840 (Cambridge 2010). His new work, in its “eco-historical” mode, performs Romantic-styled archaeology across spatial and temporal scales, and between disciplines from literary history to the Earth and atmospheric sciences. His recently published book, Tambora: The Eruption that Changed the World (Princeton 2014), reconstructs on a global scale the destructive climate deterioration arising from the massive eruption of Mt. Tambora in Indonesia in 1815. Tambora has received broad recognition—including from The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Economist, the Wall Street Journal, Nature, and the London Review of Books — and was included in Book of the Year awards by the Guardian newspaper and the London Times.