Woodblocks in Wonderland The Japanese Fairy Tale Series

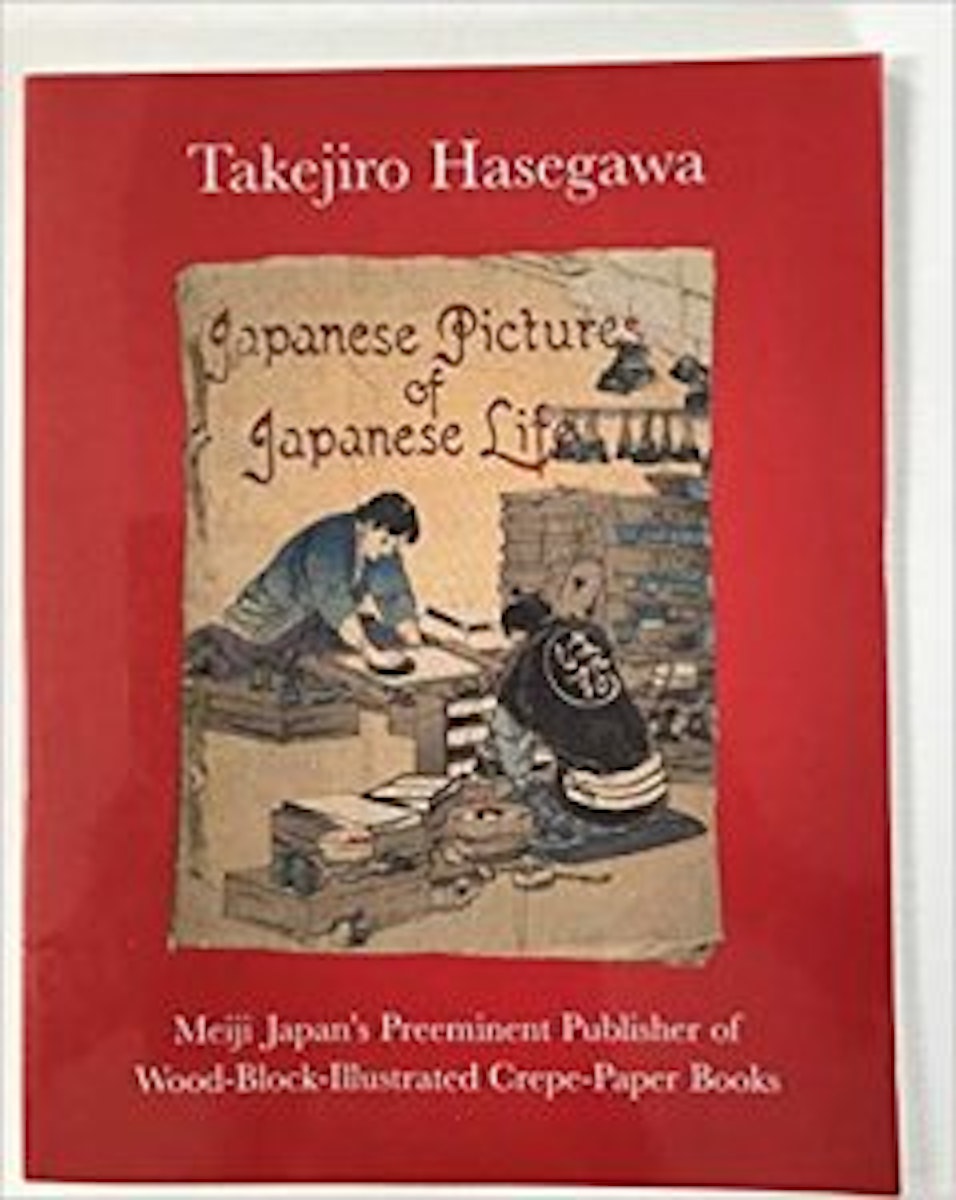

From gift-bestowing sparrows and peach-born heroes to goblin spiders and dancing phantom cats — in a series of beautifully illustrated books, the majority printed on an unusual cloth-like crepe paper, the publisher Takejiro Hasegawa introduced Japanese folk tales to the West. Christopher DeCou on how a pioneering cross-cultural endeavour gave rise to a magnificent chapter in the history of children’s publishing.

September 3, 2019

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

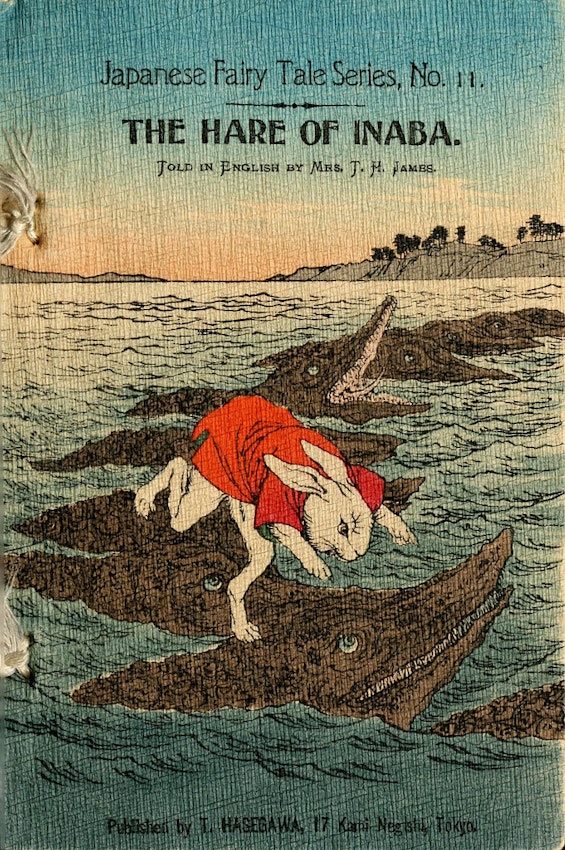

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Front cover to a ca. 1911 crepe-paper reprint of the Hare of Inaba — Source.

At the turn of the last century, the illustrated children’s books of the so-called “golden age” provided readers with many unforgettable images: think of John Tenniel’s blue-aproned Alice looking up at the sneaky grin of the Cheshire cat, or Walter Crane’s pink-dressed Belle falling in love with the boar-headed Beast. Such works are usually viewed as the exclusive realm of the great London and New York publishing houses. But on the other side of the globe, around the same time, Japan was opening its ports to the world, and in Tokyo the Kobunsha publishing company would put its own unique mark on illustrated books for children. Under the leadership of Takejiro Hasegawa, the Japanese Fairy Tale Series captured the imaginations of countless young readers with books that combined the work of western writers and translators with Japanese artists.

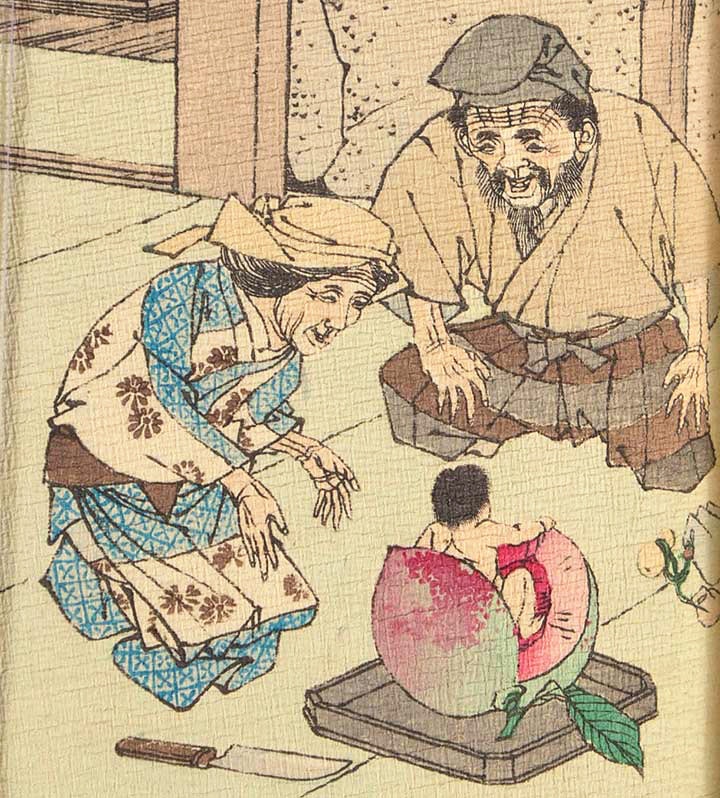

In twenty volumes, published between 1885 and 1922, the Fairy Tale series introduced traditional Japanese folk tales, first to readers of English and French, and later to readers of German, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and Russian. The tales themselves have diverse sources. Little Peachling, the first book in the series, recounts the centuries-old story of Momotaro. One day by the river, an old married couple see a giant peach. They bring it home and upon opening it are shocked to discover a little boy inside. This, of course, is Momotaro, who is raised by the old couple but later leaves them, sets off on a string of adventures, and returns a local hero.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The boy is born from the peach — illustration from a circa 1889 2nd edition crepe-paper reprint of Momotaro, or, Little Peachling — Source.

Other books in the series adapt stories rooted in Buddhist traditions. The Silly Jelly-Fish — which tells how the jellyfish, tricked by a monkey and punished by the Dragon King, comes to lose its shell — is taken from a story in which the clever monkey is a Bodhisattva, on the path to enlightenment.1

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Dragon King sends the jellyfish on his mission to fetch a monkey — illustration from a ca. 1911 crepe-paper reprint of The Silly Jelly-Fish — Source.

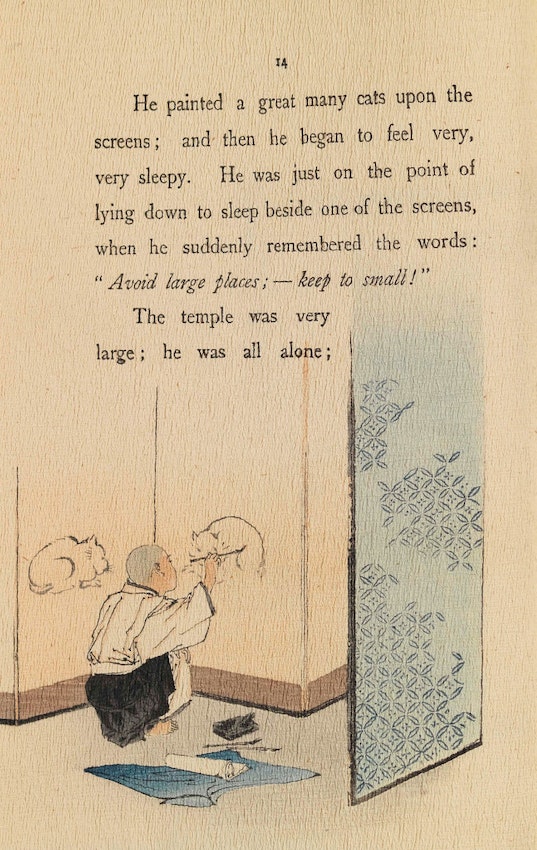

The Boy Who Drew Cats — adapted for the series by Lafcadio Hearn — tells the tale of a daydreaming boy whose drawings of cats on a monastery wall magically rid the place of a goblin rat. In traditional versions, the boy goes on to become a pious monk. In Hearn’s, he goes on to become a famous artist.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Page from the original 1898 crepe-paper edition of The Boy who Drew Cats — Source.

Initially, Takejiro Hasegawa intended to market the Fairy Tale Series to the growing education industry in Meiji Japan. Hasegawa came from a merchant family who imported western textbooks, among other goods, and his parents sent him to English schools from an early age. This put him into contact with a number of foreigners living in Japan, such as the Carrothers — husband and wife Presbyterian missionaries who ran a private school at their home2 — and made him aware of the domestic demand for English-language textbooks. His plan was to produce new educational material which would not only be composed by talented writers and translators but also handsomely crafted by Japanese artisans.3

Hasegawa modeled the aesthetic of his volumes on traditional Japanese anthologies. Starting in the sixteenth century, publishers in Japan had developed illustrated books of folk tales for children and adults, such as the remarkably beautiful Otogi-zoshi series,4 which brought together folk tales and single-author prose narratives, and the Kinmou Zui and Akahon series, which collected fantastical stories of myths, monsters, and adventures. Because the literacy rate was still low during this period, these books relied heavily on popular art styles to illustrate the narrative for the reader, with often striking results.5

In order to reproduce the effect of these earlier volumes, Hasegawa engaged traditional Japanese woodblock printers and, for the first series, used traditional mitsumata paper. Woodblock printing — the earliest form of industrial printing — was brought to Japan from China during the tenth- to thirteenth-century Song Dynasty and would become the dominant printing technology in Japan until the late nineteenth century. While movable type employs individual letters, allowing the printer to reuse the same letters on different pages, woodblocks require the printer to carve the entire page onto a single plate. Mitsumata paper — the most common Japanese paper at the time — was made from the Edgeworthia plant, which had been imported to Japan during the Edo period specifically for its papermaking qualities. The plant was harvested for its woody stems which were then cleansed of impurities and pressed in vats to create huge sheets of paper. The resulting product is creamy white, sturdy, and of a noticeable weight.6

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The envious old lady and her gift from the sparrows — page from the 1886 plain paper (mitsumata) second edition of — The Tongue-Cut Sparrow — Source.

As to the texts, for the first series of fairy-tale readers Hasegawa commissioned translations from three of his friends in the missionary community: David Thomson, Basil H. Chamberlain, and Kate James. The Reverend Thomson had come to Japan in the 1860s, became fluent in Japanese, and worked with the Carrothers at their school. He was an influential figure in Japanese Bible translation and, perhaps not surprisingly, the stories he chose to translate emphasized moral lessons, in line with Victorian values regarding the education of children. Basil H. Chamberlain, a British diplomat born to an aristocratic family, had earned a reputation as a Japanologist, writing travel books, ethnographies, and other materials about Japan. More of a scholar than the other translators — he was a professor at the Imperial Tokyo University with a particular interest in folklore — Chamberlain was the most familiar name to be associated with the first series, and certainly contributed to its popularity. He even commissioned Hasegawa to publish a special set of Ainu fairy tales, because of his personal interest in the culture of the Ainu, the indigenous community in Hokkaido.7 Kate James translated the largest number of books, and, like the Reverend Thomson, focused on stories that promoted moral lessons. She is a somewhat mysterious figure, however. We know little about her, except that she came from a Scottish clergy family, met her husband, Thomas H. James, in Constantinople, and moved with him to Japan, where she befriended his Imperial Japanese Naval Academy colleague, Basil H. Chamberlain.8 The earliest volumes in the Japanese Fairy Tale Series really were very much a product of Tokyo’s close-knit expat community.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.A rice-mortar, pounder, bee, and egg join the crabs in their council of war — illustration from a ca. 1911 crepe-paper reprint of The Battle of the Monkey and the Crab — Source.

Following the success of the first series, which appeared in 1885, Hasewaga realized he could more lucratively market the Fairy Tale Series to foreigners than to teachers and students in Japan. The artists he had engaged to illustrate the tales — Kobyashi Eitaku, Suzuki Kason, Chikanobu — were already famous for their woodblock prints in ukiyo-e style, and western audiences were immediately taken by these illustrations. Moreover, as japonisme — the trend of collecting art, artwork, and crafts from Japan — continued to grow in popularity, these prints were becoming more and more desirable to western art enthusiasts.

Starting in 1895, perhaps with japonisme in mind, Hasegawa developed a special set of books that used a more decorative Japanese paper. Chirimen, or crepe paper, is fabric-like — produced by pressing the paper fibre repeatedly and slowly rotating it. The end result is a material soft to the touch, but with rough folds and a leathery texture which makes illustrations printed on it look instantly antique.9 In fact, part of Hasegawa’s new marketing strategy was to present the books themselves as art objects and souvenirs of Japan. The area around Yokohama Bay, where international neighbourhoods had developed around the port, was a mecca for visiting collectors seeking woodblock prints and the books that featured them. But it was Hasewaga’s wheeling and dealing at World’s Fairs — not only in Tokyo but in Chicago, London, Paris, St. Louis, and Turin — that brought his books to international attention. The contacts he made at these fairs, and the prizes his books won, helped keep them in demand for decades.10

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

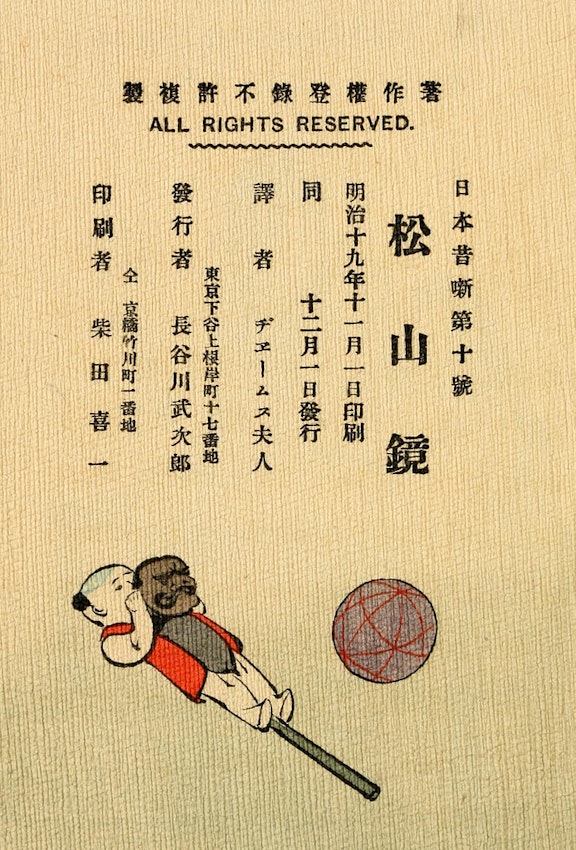

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Colophon from a circa 1911 crepe-paper edition of The Matsuyama Mirror — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

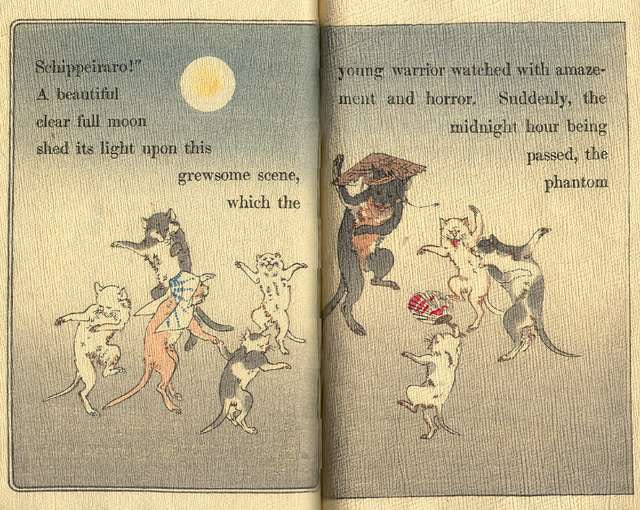

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Phantom cats dance outside the window of the young warrior — double page spread from a ca. 1902 crepe-paper reprint of Schippeitaro — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

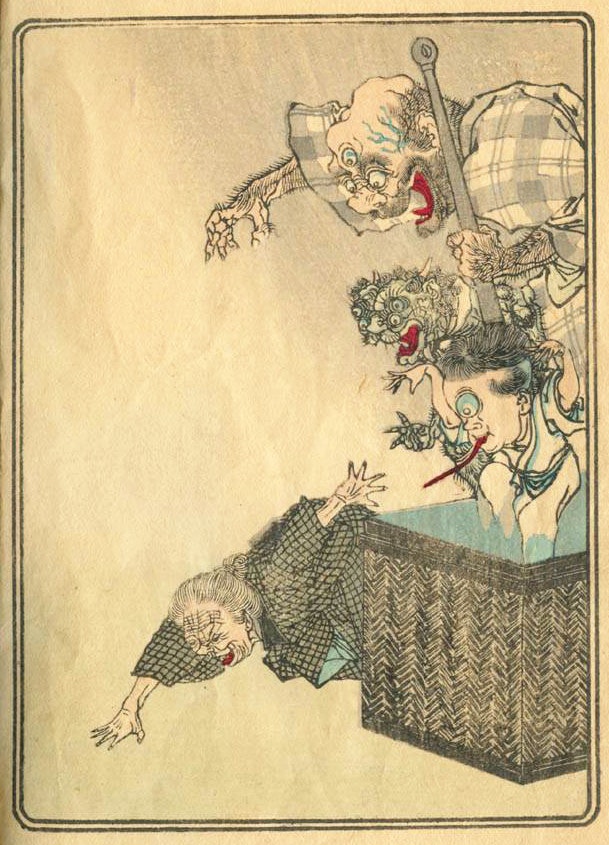

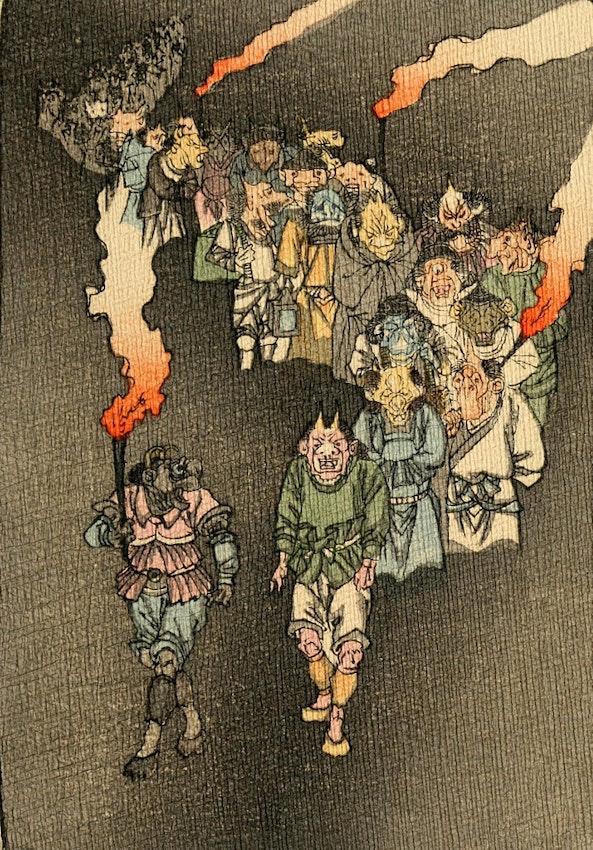

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Devils in the night — illustration from a ca. 1910 crepe-paper reprint of The Old Man & The Devils — Source.

With the ukiyo-e illustrations and the new crepe-paper editions, Hasegawa’s Fairy Tale Series attracted an even larger western audience throughout the 1890s and into the early twentieth century. Readers and reviewers alike delighted in the unfamiliar stories, which they found perfectly suited to children as well as adults. A reviewer in the Japan Weekly Mail, for example, praised Kate James’ language as being simple enough for youngsters but lacking the clichés that might prevent adults from also enjoying the books.11 In America, the stories were popular enough to be reprinted both in the widely distributed boys-and-girls’ magazine St. Nicholas12 and the Ladies Home Journal.13

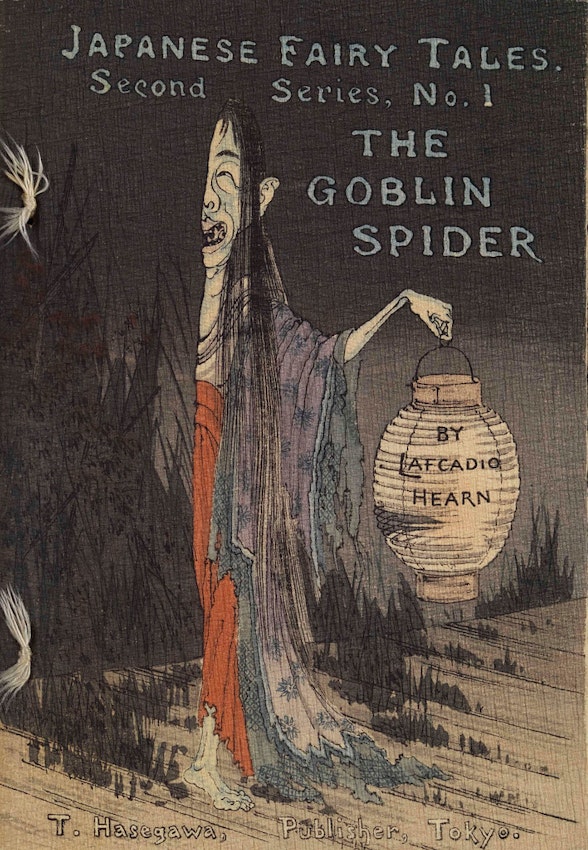

Also essential to Hasegawa’s expansion into foreign markets was his choice to commission additional stories from one of the best-known figures then associated with Japan: Lafcadio Hearn. A Greek-British writer, Hearn had risen to prominence first by writing about New Orleans and then the French West Indies. He eventually moved to Japan, married a Japanese woman, and became a Japanese citizen. Because of his intimate connections, he became somewhat of an expert on the culture and literature of the country and published numerous books and stories about Japan for western audiences. Certainly, the several stories he composed for Hasegawa’s second series increased the project’s popularity.14

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Front cover to a ca. 1910 crepe-paper reprint of The Goblin Spider — Source.

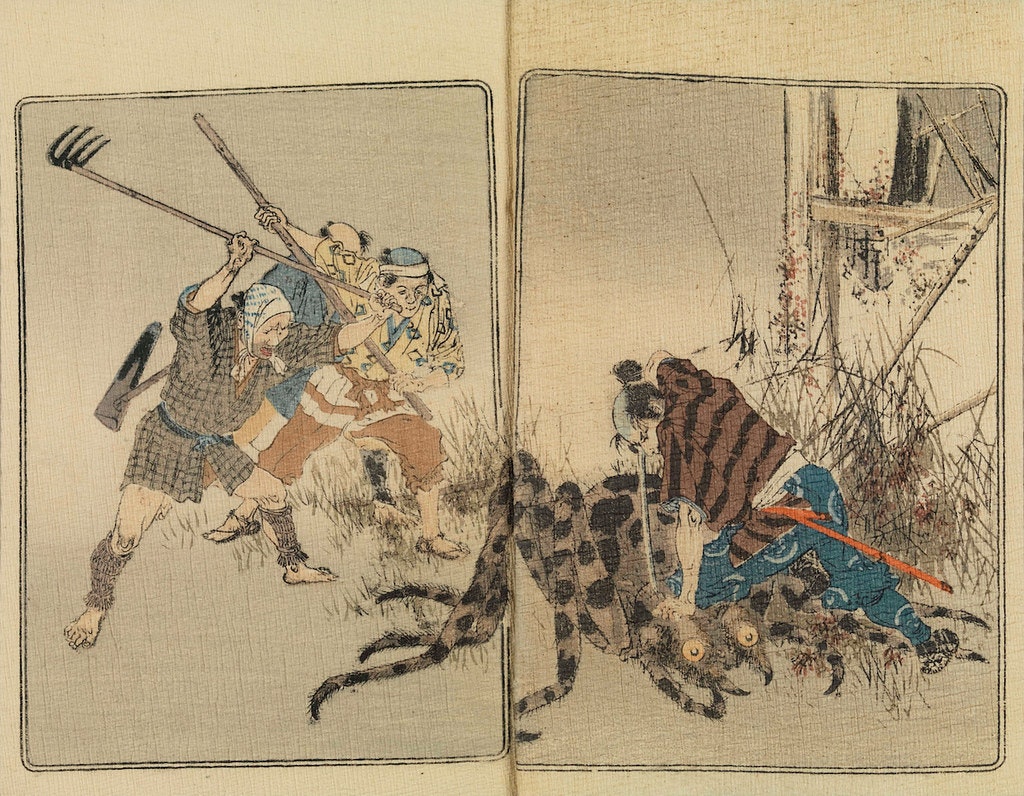

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Goblin Spider, transformed from a priest, attacks the warrior with his web — illustration from a ca. 1910 crepe-paper reprint of The Goblin Spider — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The Goblin Spider is found and killed — illustration from a ca. 1910 crepe-paper reprint of The Goblin Spider — Source.

Although the Fairy Tale Series received many positive reviews, it was not universally acclaimed. One reviewer for the Japan Weekly Mail found that, while the writing was passable, the illustrations were too fantastic. He called the lithographer lazy, because he exchanged the “traditional green [eyes] of feline orthodoxy” with odd yellow eyes.15 Other reviewers also thought the drawings were not up to par. In the San Francisco Daily Bulletin, an especially prejudiced reviewer said the books were just too “Japanese”, “barbarous and ill-calculated”, adding that the crepe paper was impractical for reading and made for a “flimsy” book.16

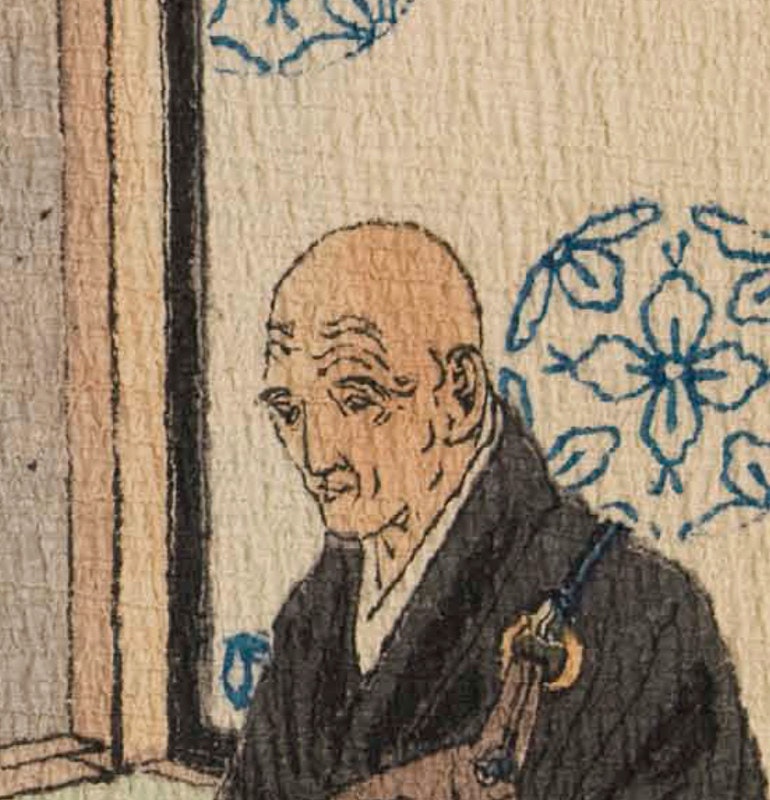

The reviewer’s doubts about the advisability of printing on crepe paper were shared even by the unprejudiced. Lafcadio Hearn himself, in a letter to Hasegawa, argued against the crepe’s roughcast texture and the resultant loss of visual detail:

Indeed, I prefer the old sets of the Fairy Series on plain paper, — not only because the drawings come out better, but because the larger print is better for children’s eyes. (I want to buy a plain set at some future time.) In the case of my own story, I think that much of the delicate beauty of the charming drawings is lost in the crepe edition, -- especially the finely expressive lines of the old priest’s face, and the character-studies of the peasant oya in the opening pictures.17

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Detail of the priest — from the original 1898 crepe-paper edition of The Boy who Drew Cats — Source.

Ironically, it was the crêpe books that continued to sell, as novelty items prized for their unique paper and illustrations, well into the twentieth century, even after Hasegawa’s series had begun to compete with other collections of Japanese fairy tales marketed to children. American and British textbook writers, too, started including Japanese stories among their educational materials, which reduced the novelty and uniqueness of the endeavor. The last volume in the series, Hearn’s version of a fairy tale called The Fountain of Youth, was published in 1922 (although the publishing company continued to reprint further editions until after World War II).

Looking back, we can see that the books in the Japanese Fairy Tale Series blended simple storytelling and striking images with an elegance comparable to any of the more widely known masterpieces of the golden age of children’s illustrations. At a time when publishing houses in London and New York dominated the market, Hasegawa’s press in Tokyo was producing equally beautiful volumes using traditional Japanese craftwork and broadcasting Japan’s culture to the world. Today, anime and manga represent flourishing new forms through which that culture is reaching global audiences, but, in the words of arts and crafts historian Ann Herring, “in the area of export in the form of translations for young readers, the record of the Meiji era remains unexcelled.”18

Christopher DeCou is researching his PhD at the University of Michigan and writes about science and history.

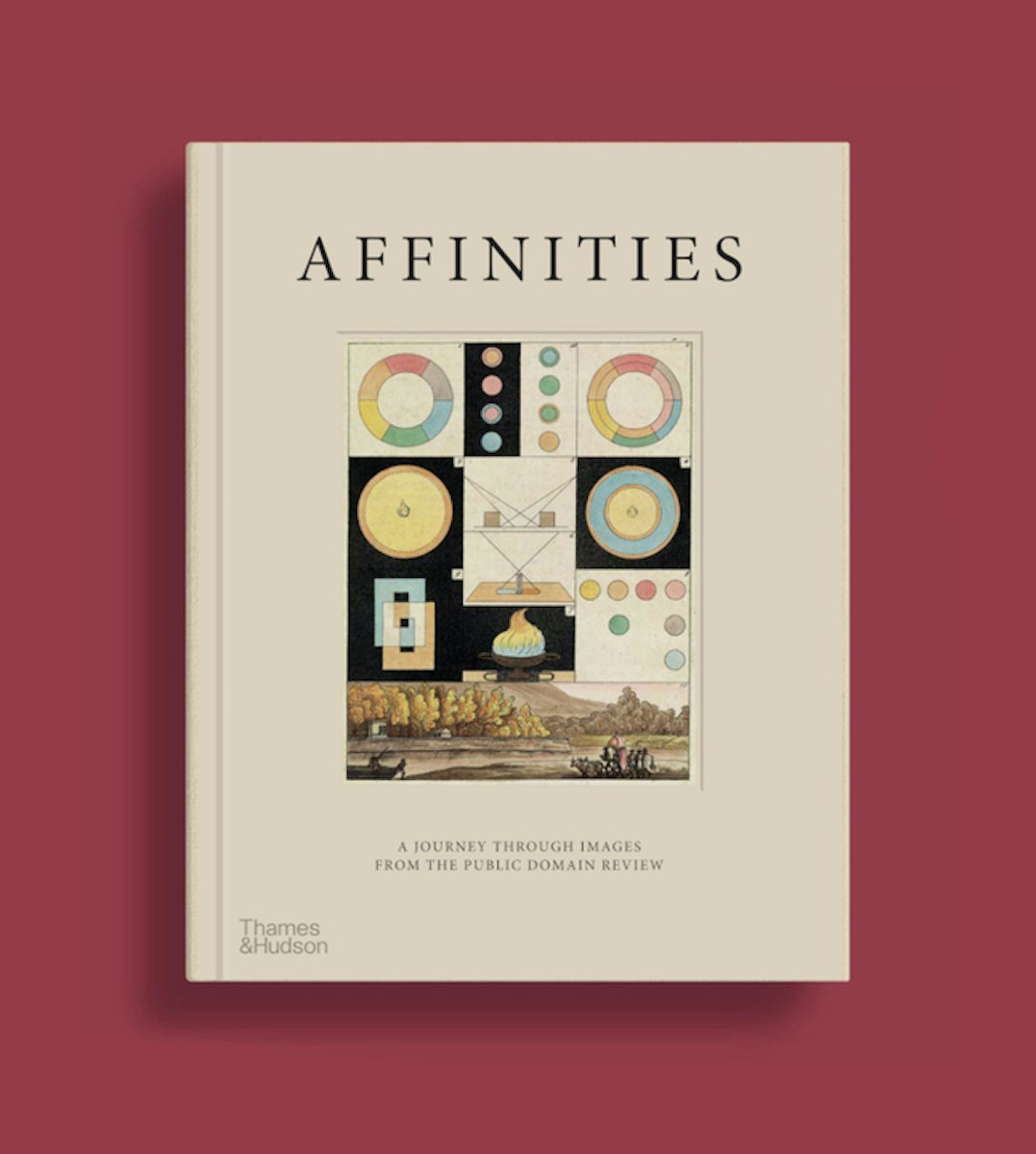

Imagery from this post is featured in

Affinities

our special book of images created to celebrate 10 years of The Public Domain Review.

500+ images – 368 pages

Large format – Hardcover with inset image