From a speed and safety perspective, it was a huge advancement over the slower, more dangerous hot metal-type systems that came before it.

But… our phototypesetting machine only had ten typeface options! Of those, Helvetica, Palatino, and Times New Roman were the only fonts really worth using.

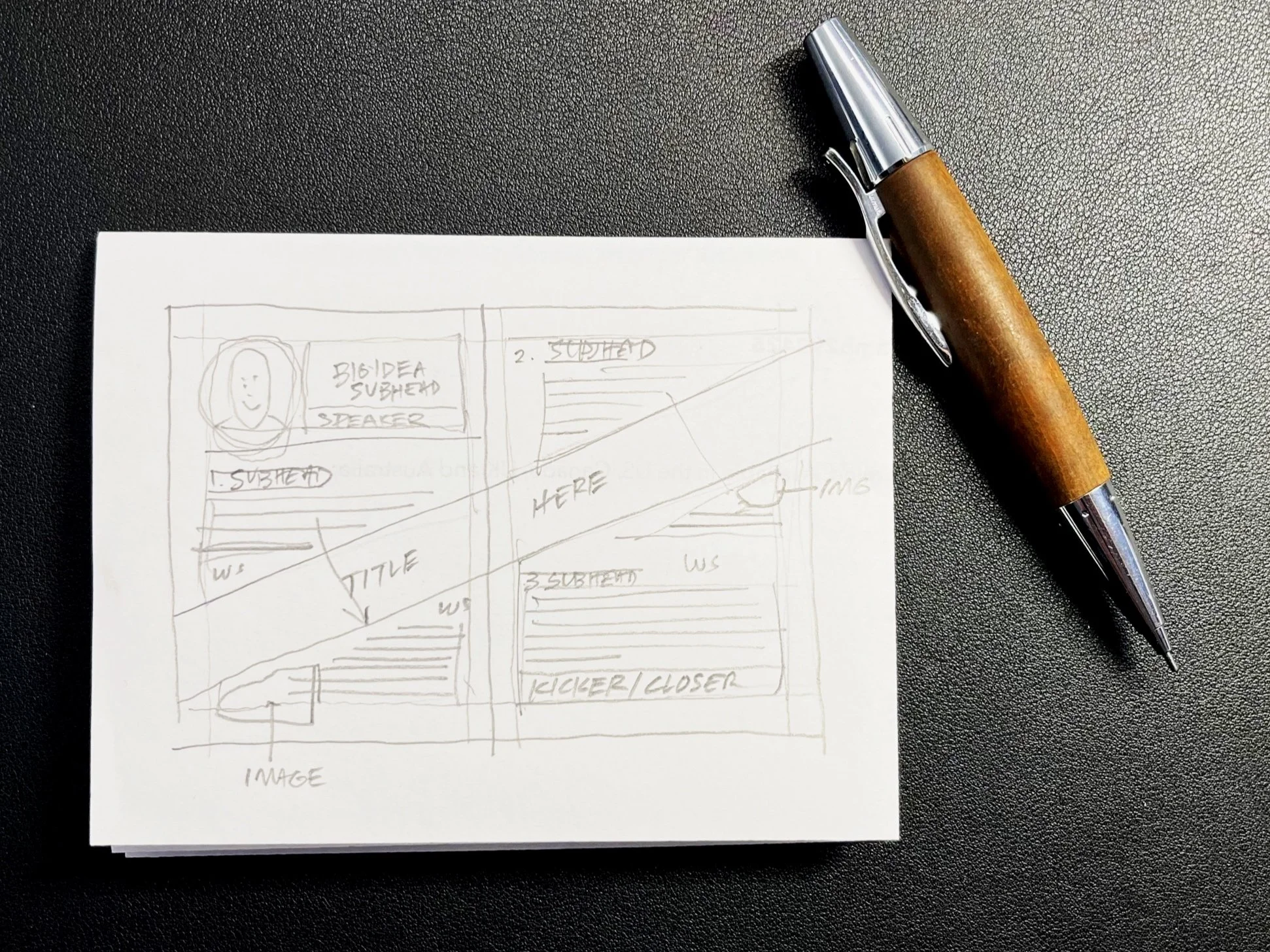

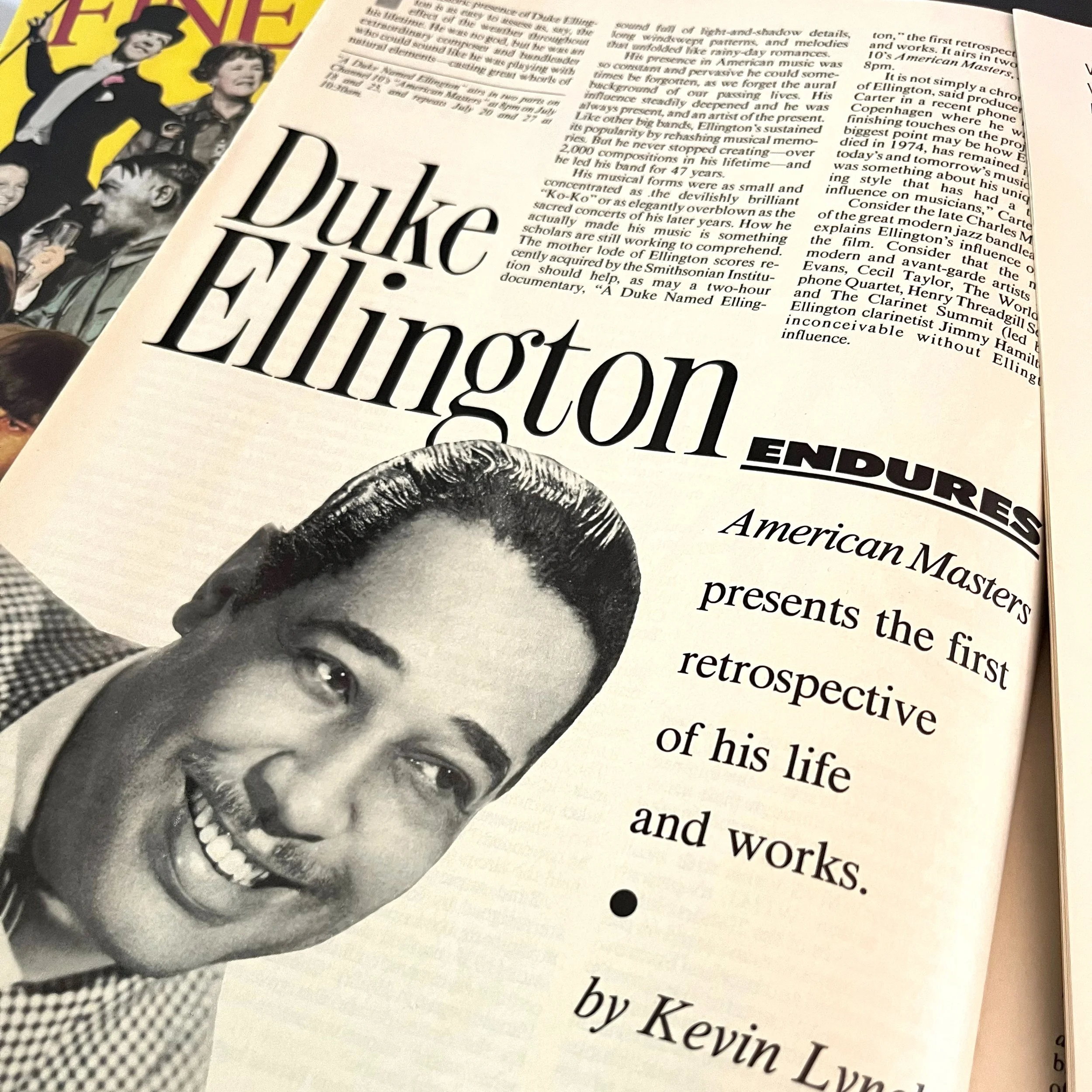

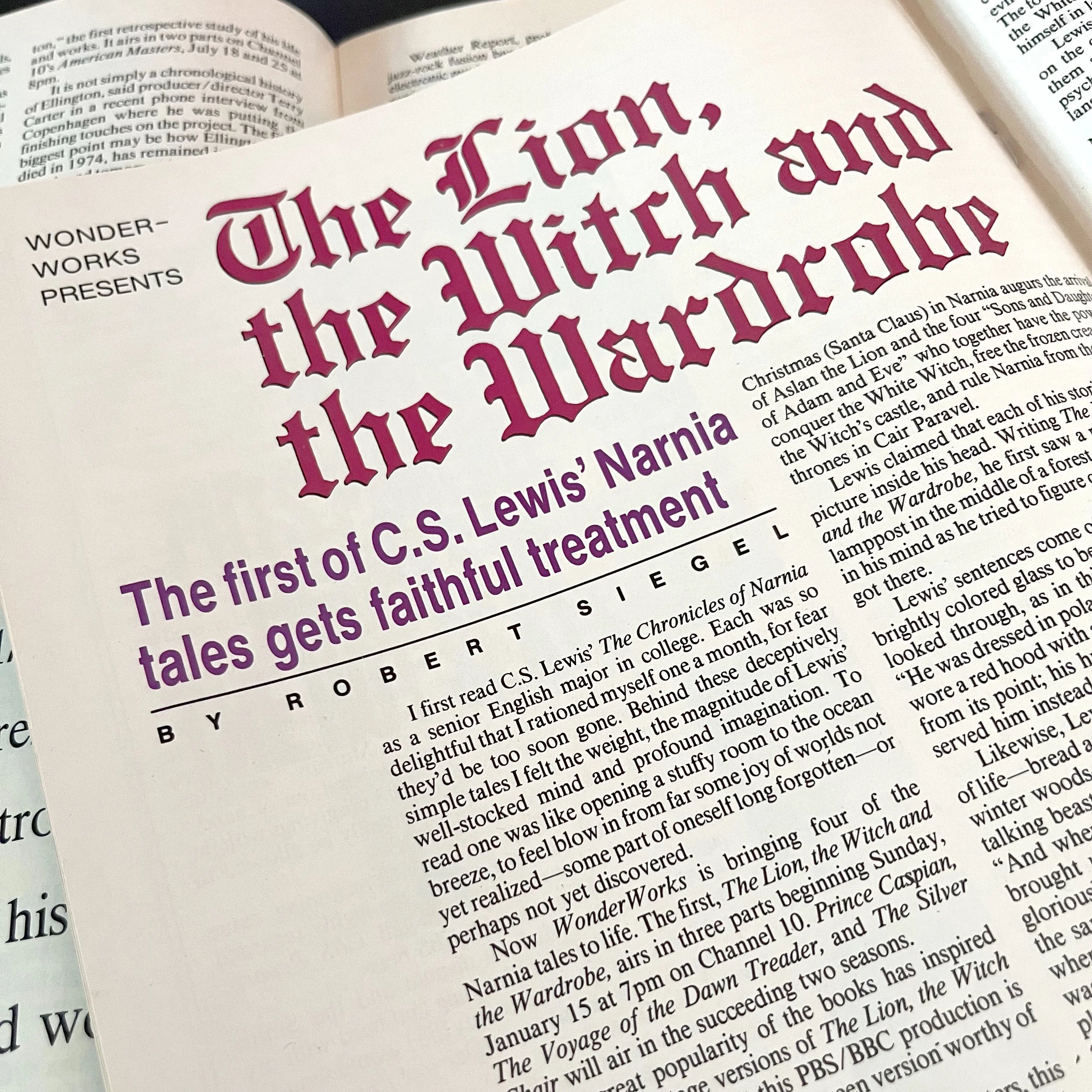

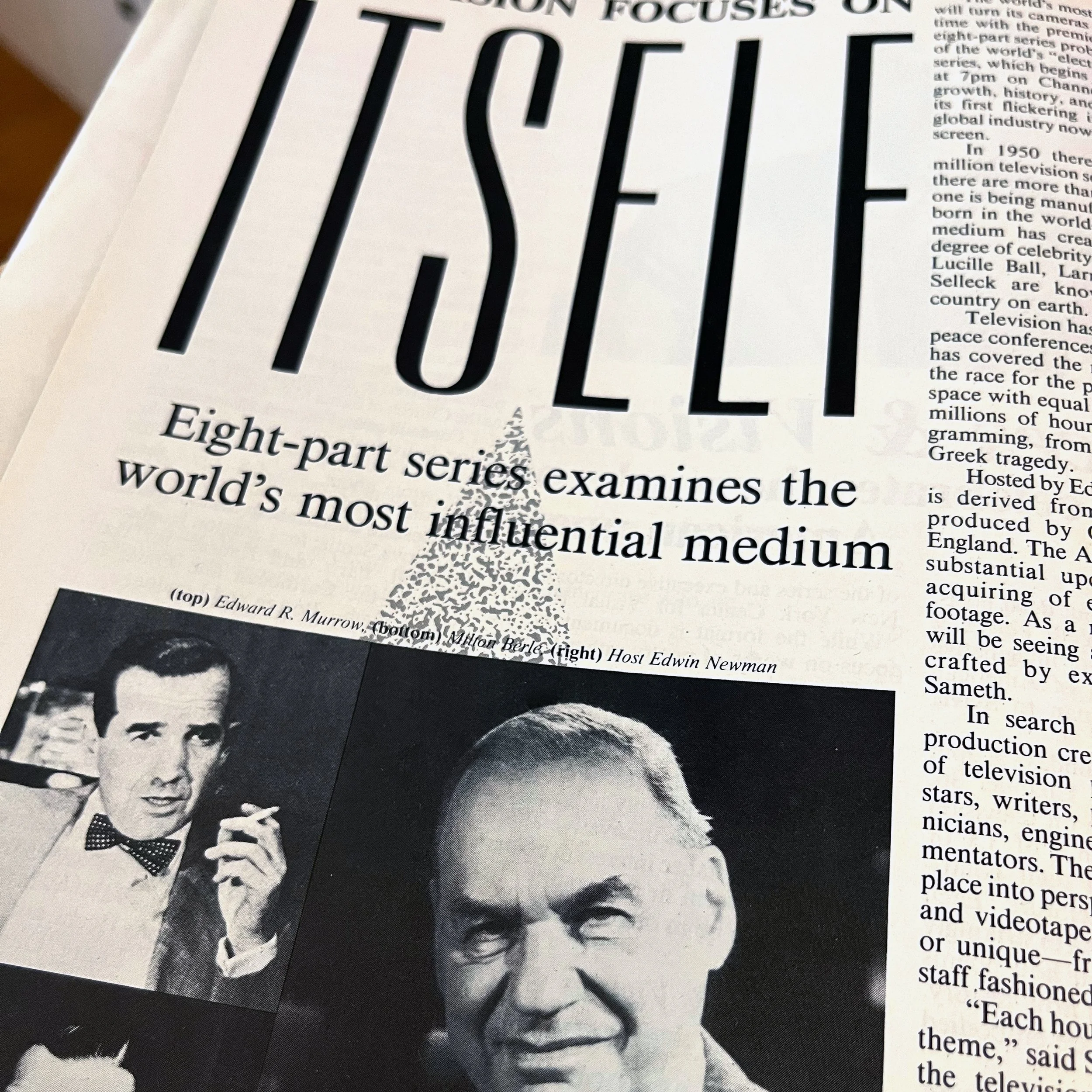

This presented a problem, particularly with magazine layouts: being a huge fan of design magazines Communication Arts and PRINT, I wanted to use cool headlines and exciting layouts in my article designs.

Ten typefaces would not cut it.

As fortune would have it, we had two things in our studio that helped me get around the ten-typeface problem:

A photostat camera in the back of our studio. This giant, stationary camera was designed to reproduce black-and-white images at different sizes, ready for print production.

Stacks of type specimen catalogs filled with hundreds of unique typefaces. Each catalog contained two-page spreads with an entire alphabet, numerals, and special characters… perfect for photographing.

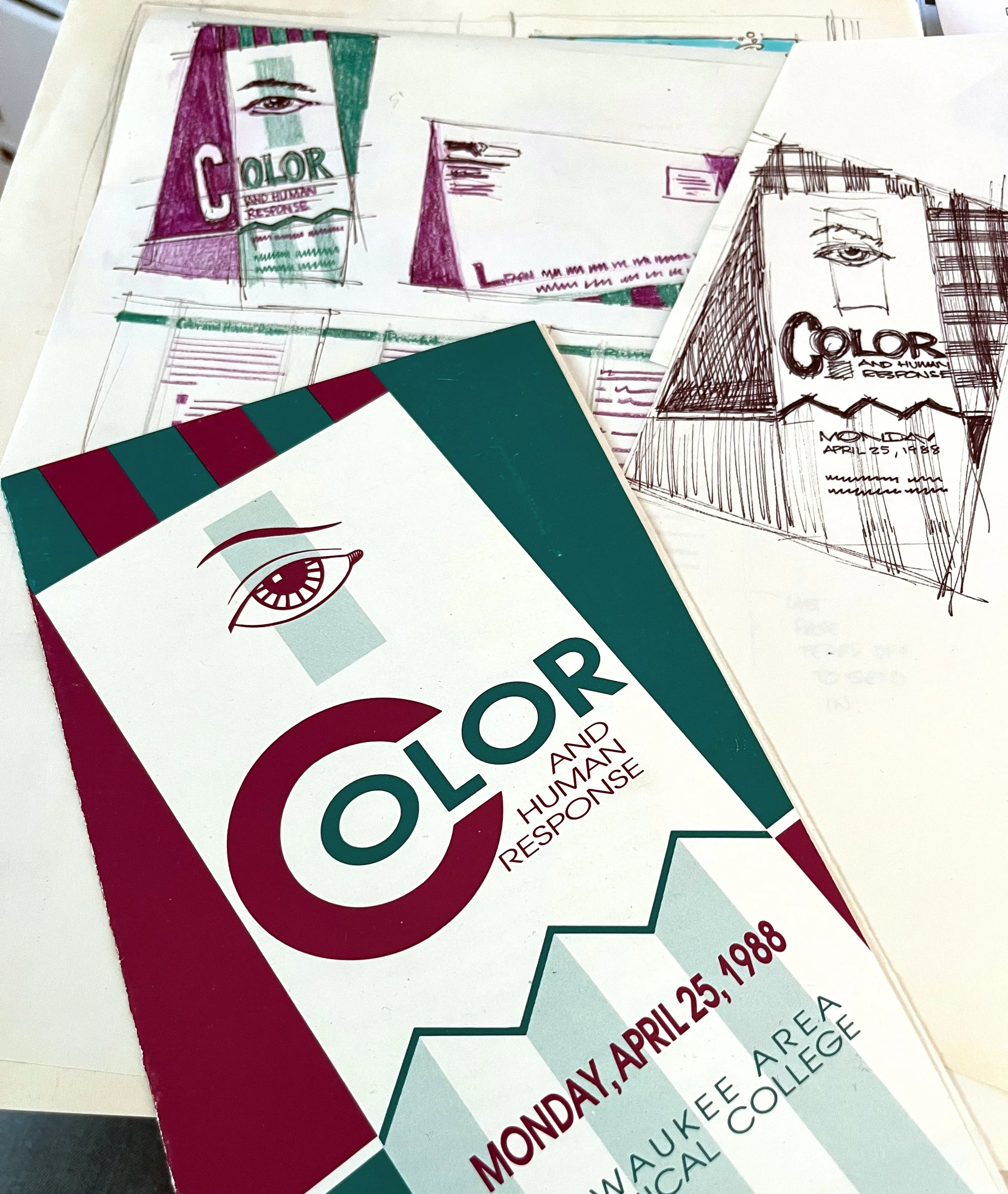

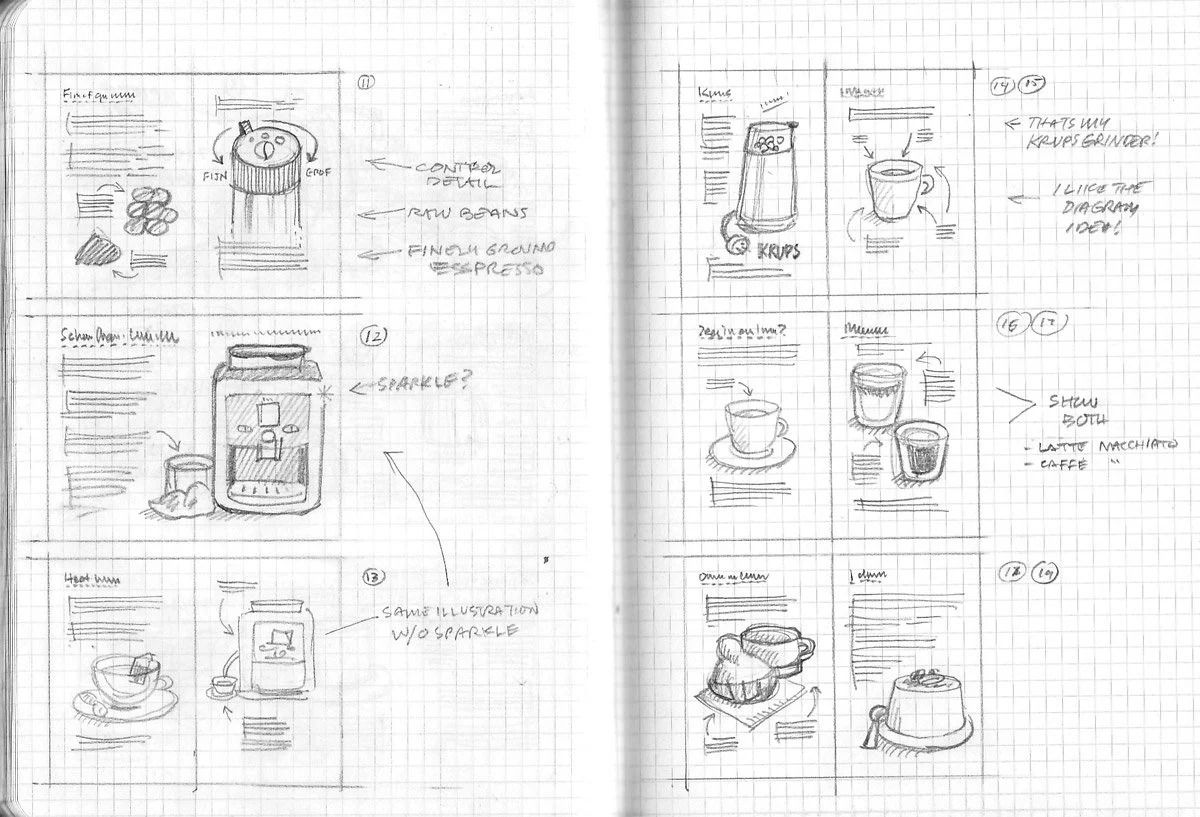

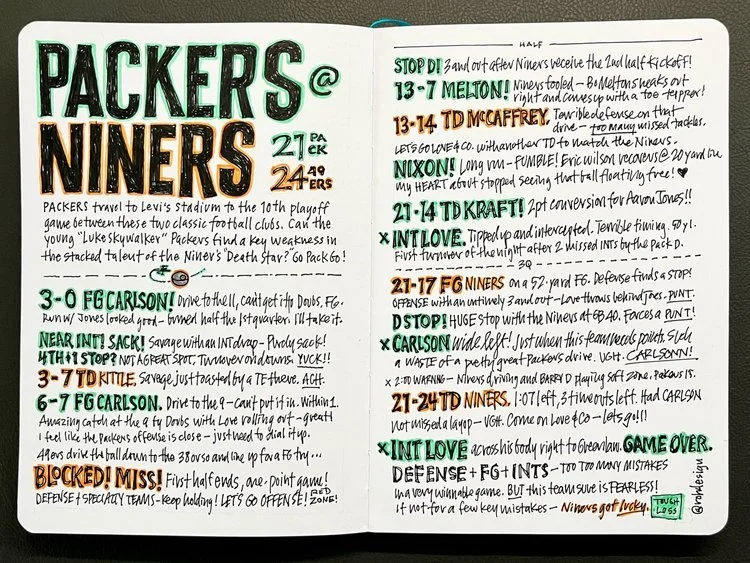

I’d page through the type catalogs until I found the perfect headline font for my magazine layout sketch.

I’d secure the book, spread side up, in the camera bed, take a shot with the photostat camera and print ten to fifteen copies of the typeface for paste-up.

Back at my desk with the stack of photostat typeface prints, I’d wax the sheets and methodically cut each letter out with an X-Acto blade knife.

Then, I would carefully place each glyph into my layout. I was a stickler for kerning (the space between letters) because I wanted the headlines to flow smoothly across the page.