Italian language in Croatia

The Italian language is an official minority language in Croatia, with many schools and public announcements published in both languages. Croatia's proximity and cultural connections to Italy have led to a relatively large presence of Italians in Croatia.

Italians were recognized as a state minority in the Croatian Constitution in two sections: Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians. Their numbers drastically decreased following the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus (1943–1960). Even though today only 0.43% of the total population is Italian by citizenship, many more are ethnically Italian and a large percentage of Croatians speak Italian, in addition to Croatian.

As of 2009, the Italian language is officially used in twenty cities and municipalities and ten other settlements in Croatia, according to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[1] It is an officially recognized minority language in Istria County, where it is spoken by 6.83% of the population on the aggregate and closer to 50% of the population in certain subdivisions.[2] An estimated 14% of Croats speak Italian as a second language, which is one of the highest percentages in the European Union.[3]

Italian-speaking population

[edit]

The 2011 Census in Croatia reported 17,807 ethnic Italians in the country (some 0.42% of the total population).[4] Ethnologue reported 70,000 persons whose first language is Italian or Venetian in 1998 (referring to Eugen Marinov's 1998 data). This population was composed of 30,000 ethnic Italians[5] and 40,000 ethnic Croats and persons declared regionally ("as Istrians"). Native Italian speakers are largely concentrated along the western coast of peninsula Istria. Because of Croatian trade and tourist relations with Italy, many Croats have some knowledge of the language (mostly in the service and tourist industries).

In Istrian contexts the word "Italian" can just as easily refer to autochthonous speakers of the Venetian language, who were present in the region before the inception of the Venetian Republic and of the Istriot language, the oldest spoken language in Istria, dating back to the Romans and now spoken in the south west of Istria in Rovigno, Valle, Dignano, Gallesano, Fasana, Valbandon, Sissano and the surroundings of Pola.

The term may sometimes refer to a descendant of colonized persons during the Benito Mussolini period (during that period immigration in Istria, Zadar/Zara and northern Adriatic islands, given to Italy after World War I, was promoted, 44,000 according to Žerjavić,[6]). It can also refer to Istrian Slavs who adopted Italian culture as they moved from rural to urban areas, or from the farms into the bourgeoisie.

History

[edit]

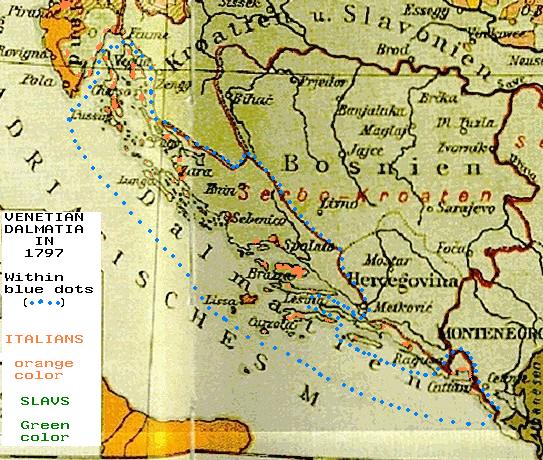

Via conquests, the Republic of Venice, from the 9th century until 1797, when it was conquered by Napoleon, extended its dominion to coastal parts of Istria and Dalmatia.[7] Pula/Pola was an important centre of art and culture during the Italian Renaissance.[8] The coastal areas and cities of Istria came under Venetian Influence in the 9th century. In 1145, the cities of Pula, Koper and Izola rose against the Republic of Venice but were defeated, and were since further controlled by Venice.[9] On 15 February 1267, Poreč was formally incorporated with the Venetian state.[10] Other coastal towns followed shortly thereafter. The Republic of Venice gradually dominated the whole coastal area of western Istria and the area to Plomin on the eastern part of the peninsula.[9] Dalmatia was first and finally sold to the Republic of Venice in 1409 but Venetian Dalmatia wasn't fully consolidated from 1420.[11]

From the Middle Ages onwards numbers of Slavic people near and on the Adriatic coast were ever increasing, due to their expanding population and due to pressure from the Ottomans pushing them from the south and east.[12][13] This led to Italic people becoming ever more confined to urban areas, while the countryside was populated by Slavs, with certain isolated exceptions.[14] In particular, the population was divided into urban-coastal communities (mainly Romance speakers) and rural communities (mainly Slavic speakers), with small minorities of Morlachs and Istro-Romanians.[15] From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, Italian and Slavic communities in Istria and Dalmatia had lived peacefully side by side because they did not know the national identification, given that they generically defined themselves as "Istrians" and "Dalmatians", of "Romance" or "Slavic" culture.[16]

After the fall of Napoleon (1814), Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia were annexed to the Austrian Empire.[17] Many Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the Risorgimento movement that fought for the unification of Italy.[18] However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria and Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic. This triggered the gradual rise of Italian irredentism among many Italians in Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia, who demanded the unification of the Julian March, Kvarner and Dalmatia with Italy. The Italians in Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia supported the Italian Risorgimento: as a consequence, the Austrians saw the Italians as enemies and favored the Slav communities of Istria, Kvarner and Dalmatia,.[19]

During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[20]

His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard. His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.

Istrian Italians were more than 50% of the total population of Istria for centuries,[22] while making up about a third of the population in 1900.[23] Dalmatia, especially its maritime cities, once had a substantial local ethnic Italian population (Dalmatian Italians), making up 33% of the total population of Dalmatia in 1803,[24][25] but this was reduced to 20% in 1816.[26] In Dalmatia there was a constant decline in the Italian population, in a context of repression that also took on violent connotations.[27] During this period, Austrians carried out an aggressive anti-Italian policy through a forced Slavization of Dalmatia.[28] According to Austrian census, the Dalmatian Italians formed 12.5% of the population in 1865.[29] In the 1910 Austro-Hungarian census, Istria had a population of 57.8% Slavic-speakers (Croat and Slovene), and 38.1% Italian speakers.[30] For the Austrian Kingdom of Dalmatia, (i.e. Dalmatia), the 1910 numbers were 96.2% Slavic speakers and 2.8% Italian speakers.[31] Another contributing factor was the lack of a religious barrier, with Italians often intermarrying with and being assimilated by their more numerous Croatian neighbors. In 1909 the Italian language lost its status as the official language of Dalmatia in favor of Croatian only (previously both languages were recognized): thus Italian could no longer be used in the public and administrative sphere.[32] In Rijeka the Italians were the relative majority in the municipality (48.61% in 1910), and in addition to the large Croatian community (25.95% in the same year), there was also a fair Hungarian minority (13.03%). According to the official Croatian census of 2011, there are 2,445 Italians in Rijeka (equal to 1.9% of the total population).[33]

The Italian population in Dalmatia was concentrated in the major cities. In the city of Split in 1890 there were 1,969 Dalmatian Italians (12.5% of the population), in Zadar 7,423 (64.6%), in Šibenik 1,018 (14.5%) and in Dubrovnik 331 (4.6%).[34] In other Dalmatian localities, according to Austrian censuses, Dalmatian Italians experienced a sudden decrease: in the twenty years 1890-1910, in Rab they went from 225 to 151, in Vis from 352 to 92, in Pag from 787 to 23, completely disappearing in almost all the inland locations.

In 1915, Italy declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire,[35] leading to bloody conflict mainly on the Isonzo and Piave fronts. Britain, France and Russia had been "keen to bring neutral Italy into World War I on their side. However, Italy drove a hard bargain, demanding extensive territorial concessions once the war had been won".[36] In a deal to bring Italy into the war, under the London Pact, Italy would be allowed to annex not only Italian-speaking Trentino and Trieste, but also German-speaking South Tyrol, Istria (which included large non-Italian communities), and the northern part of Dalmatia including the areas of Zadar (Zara) and Šibenik (Sebenico). Mainly Italian Fiume (present-day Rijeka) was excluded.[36]

In November 1918, after the surrender of Austria-Hungary, Italy occupied militarily Trentino Alto-Adige, the Julian March, Istria, the Kvarner Gulf and Dalmatia, all Austro-Hungarian territories. On the Dalmatian coast, Italy established the Governorate of Dalmatia, which had the provisional aim of ferrying the territory towards full integration into the Kingdom of Italy, progressively importing national legislation in place of the previous one. The administrative capital was Zara. The Governorate of Dalmatia was evacuated following the Italo-Yugoslav agreements which resulted in the Treaty of Rapallo (1920). After the war, the Treaty of Rapallo between the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and the Kingdom of Italy (12 November 1920), Italy annexed Zadar in Dalmatia and some minor islands, almost all of Istria along with Trieste, excluding the island of Krk, and part of Kastav commune, which mostly went to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. By the Treaty of Rome (27 January 1924), the Free State of Fiume (Rijeka) was divided between Italy and Yugoslavia.[37] Furthermore, after World War I and the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, 10,000 Italians in the Governatorato took Yugoslav citizenship so they could remain and be accepted by the new Yugoslavian state.[38]

In 1939 Italy conducted a covert census of the non-Italian population (Croats and Slovenes) in Istria, Kvarner, Zadar, Trieste and Gorizia. After the census, Italian authorities publicly stated that the Italian speaking population in those areas had increased. However, data proved that the share of Croatian speakers did not diminish in that period.[39]

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia attempted a policy of forced Croatisation against the Italian minority in Dalmatia.[40] The majority of the Italian Dalmatian minority decided to transfer in the Kingdom of Italy.[41] Following the Wehrmacht invasion of Yugoslavia (6 April 1941) during World War II, the Italian zone of occupation was further expanded.[42] Italy annexed large areas of Croatia (including most of coastal Dalmatia) and Slovenia (including its capital Ljubljana).[43] During World War II the Kingdom of Italy annexed most of Dalmatia to the second Governatorato di Dalmazia. In 1942, 4020 Italians lived in these newly annexed areas: 2,220 in Spalato (Split), 300 in Sebenico (Šibenik), 500 in Cattaro (Kotor) and 1000 in Veglia (Krk).

For various reasons—mainly related to nationalism and armed conflict—the numbers of Italian speakers in Croatia declined during the 20th century, especially after the World War II in a period known as the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus, when about 90% Italian-speaking Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians left Yugoslav dominated areas in the eastern Adriatic, corresponding to 230,000-350,000 people,[44][45] between 1943 and the late 1950s. The Italians who remained in Yugoslavia, gathered in the Italian Union, were recognized as a national minority, with their own flag. The 2001 census in Croatia reported 19,636 ethnic Italians in the country.[46]

In 2001 about 500 Dalmatian Italians were counted in Dalmatia. In particular, according to the official Croatian census of 2011, there are 83 Dalmatian Italians in Split (equal to 0.05% of the total population), 16 in Šibenik (0.03%) and 27 in Dubrovnik (0.06%).[47] According to the official Croatian census of 2021, there are 63 Dalmatian Italians in Zadar (equal to 0.09% of the total population).[48]

Geographic distribution and population

[edit]

In many municipalities in the Istrian region (Croatia) there are bilingual statutes, and the Italian language is considered to be a co-official language. The proposal to raise Italian to a co-official language, as in the Istrian Region, has been under discussion for years.

By recognizing and respecting its cultural and historical legacy, the City of Rijeka ensures the use of its language and writing to the Italian indigenous national minority in public affairs relating to the sphere of self-government of the City of Rijeka. The City of Fiume, within the scope of its possibilities, ensures and supports the educational and cultural activity of the members of the indigenous Italian minority and its institutions.[49]

In various municipalities, census data shows that significant numbers of Italians still live in Istria, such as 51% of the population of Grožnjan/Grisignana, 37% at Brtonigla/Verteneglio, and nearly 30% in Buje/Buie.[50] In the village there, it is an important section of the "Comunità degli Italiani" in Croatia.[51] Italian is co-official with Croatian in nineteen municipalities in the Croatian portion of Istria: Buje (Italian: Buie), Novigrad (Italian: Cittanova), Izola (Italian: Isola d'Istria), Vodnjan (Italian: Dignano), Poreč (Italian: Parenzo, Pula (Italian: Pola, Rovinj (Italian: Rovigno, Umag (Italian: Umago, Bale (Italian: Valle d'Istria, Brtonigla (Italian: Verteneglio, Fažana (Italian: Fasana, Grožnjan (Italian: Grisignana), Kaštelir-Labinci (Italian: Castellier-Santa Domenica), Ližnjan (Italian: Lisignano), Motovun (Italian: Montona), Oprtalj (Italian: Portole), Višnjan (Italian: Visignano), Vižinada (Italian: Visinada) and Vrsar (Italian: Orsera).[52] The daily newspaper La Voce del Popolo, the main newspaper for Italian Croatians, is published in Rijeka/Fiume.

Education and Italian language

[edit]

Beside Croat language schools, in Istria there are also kindergartens in Buje/Buie, Brtonigla/Verteneglio, Novigrad/Cittanova, Umag/Umago, Poreč/Parenzo, Vrsar/Orsera, Rovinj/Rovigno, Bale/Valle, Vodnjan/Dignano, Pula/Pola and Labin/Albona, as well as primary schools in Buje/Buie, Brtonigla/Verteneglio, Novigrad/Cittanova, Umag/Umago, Poreč/Parenzo, Vodnjan/Dignano, Rovinj/Rovigno, Bale/Valle and Pula/Pola, as well as lower secondary schools and upper secondary schools in Buje/Buie, Rovinj/Rovigno and Pula/Pola, all with Italian as the language of instruction.

The city of Rijeka/Fiume in the Kvarner/Carnaro region has Italian kindergartens and elementary schools, and there is an Italian Secondary School in Rijeka.[53] The town of Mali Lošinj/Lussinpiccolo in the Kvarner/Carnaro region has an Italian kindergarten.

In Zadar, in Dalmatia/Dalmazia region, the local Community of Italians has requested the creation of an Italian kindergarten since 2009. After considerable government opposition,[54][55] with the imposition of a national filter that imposed the obligation to possess Italian citizenship for registration, in the end in 2013 it was opened hosting the first 25 children.[56] This kindergarten is the first Italian educational institution opened in Dalmatia after the closure of the last Italian school, which operated there until 1953.

Since 2017, a Croatian primary school has been offering the study of the Italian language as a foreign language. Italian courses have also been activated in a secondary school and at the faculty of literature and philosophy.[57]

See also

[edit]- Minority languages of Croatia

- Italian language in Slovenia

- Dalmatian Italians

- Istrian Italians

- Istrian–Dalmatian exodus

References

[edit]- ^ "Europska povelja o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima" (in Croatian). Ministry of Justice (Croatia). 2011-04-12. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ^ "Population by Mother Tongue, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ^ Directorate General for Education and Culture; Directorate General Press and Communication (2006). Europeans and their Languages (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ^ Ethnologue Ethnologue report for Croatia

- ^ "Prešućivanje s poznatom namjerom". Vjesnik (in Croatian). May 28, 2003. Archived from the original on September 18, 2003.

- ^ Alvise Zorzi, La Repubblica del Leone. Storia di Venezia, Milano, Bompiani, 2001, ISBN 978-88-452-9136-4., pp. 53-55 (in italian)

- ^ Prominent Istrians

- ^ a b "Historic overview-more details". Istra-Istria.hr. Istria County. Retrieved 19 December 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ John Mason Neale, Notes Ecclesiological & Picturesque on Dalmatia, Croatia, Istria, Styria, with a visit to Montenegro, pg. 76, J.T. Hayes - London (1861)

- ^ "Dalmatia history". Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Region of Istria: Historic overview-more details". Istra-istria.hr. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Jaka Bartolj. "The Olive Grove Revolution". Transdiffusion. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010.

While most of the population in the towns, especially those on or near the coast, was Italian, Istria's interior was overwhelmingly Slavic – mostly Croatian, but with a sizeable Slovenian area as well.

- ^ "Italian islands in a Slavic sea". Arrigo Petacco, Konrad Eisenbichler, A tragedy revealed, p. 9.

- ^ ""L'Adriatico orientale e la sterile ricerca delle nazionalità delle persone" di Kristijan Knez; La Voce del Popolo (quotidiano di Fiume) del 2/10/2002" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "L'ottocento austriaco" (in Italian). 7 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Trieste, Istria, Fiume e Dalmazia: una terra contesa" (in Italian). Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ a b Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971

- ^ Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848/1867. V Abteilung: Die Ministerien Rainer und Mensdorff. VI Abteilung: Das Ministerium Belcredi, Wien, Österreichischer Bundesverlag für Unterricht, Wissenschaft und Kunst 1971, vol. 2, p. 297. Citazione completa della fonte e traduzione in Luciano Monzali, Italiani di Dalmazia. Dal Risorgimento alla Grande Guerra, Le Lettere, Firenze 2004, p. 69.)

- ^ Jürgen Baurmann, Hartmut Gunther and Ulrich Knoop (1993). Homo scribens : Perspektiven der Schriftlichkeitsforschung (in German). Walter de Gruyter. p. 279. ISBN 3484311347.

- ^ "Istrian Spring". Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 886–887.

- ^ Bartoli, Matteo (1919). Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia (in Italian). Tipografia italo-orientale. p. 16.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy from Liberalism to Fascism, 1870–1925. Methuen. p. 107. ISBN 9780416189407.

- ^ "Dalmazia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 729

- ^ Raimondo Deranez (1919). Particolari del martirio della Dalmazia (in Italian). Ancona: Stabilimento Tipografico dell'Ordine.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Angelo Filipuzzi (1966). La campagna del 1866 nei documenti militari austriaci: operazioni terrestri (in Italian). University of Padova. p. 396.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Peričić, Šime (2003-09-19). "O broju Talijana/talijanaša u Dalmaciji XIX. stoljeća". Radovi Zavoda za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru (in Croatian) (45): 342. ISSN 1330-0474.

- ^ "Spezialortsrepertorium der österreichischen Länder I-XII, Wien, 1915–1919". Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Spezialortsrepertorium der österreichischen Länder I-XII, Wien, 1915–1919". Archived from the original on 2013-05-29.

- ^ "Dalmazia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 730

- ^ "Croatian Bureau of Statistics". Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Guerrino Perselli, I censimenti della popolazione dell'Istria, con Fiume e Trieste e di alcune città della Dalmazia tra il 1850 e il 1936, Centro di Ricerche Storiche - Rovigno, Unione Italiana - Fiume, Università Popolare di Trieste, Trieste-Rovigno, 1993

- ^ "First World War.com – Primary Documents – Italian Entry into the War, 23 May 1915". Firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ a b "First World War.com – Primary Documents – Treaty of London, 26 April 1915". Firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Lo Stato libero di Fiume:un convegno ne rievoca la vicenda" (in Italian). 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Rodogno, D. (2006). Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–72. ISBN 9780521845151. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ Časopis za suvremenu povijest br. 3/2002. M. Manin: O povjerljivom popisivanju istarskih Hrvata provedenom 1939. godine (na temelju popisnoga materijala iz 1936. godine)

(Journal of Contemporary History: Secret Census of Istrian Croats held in 1939 based on 1936 Census Data), summary in English - ^ "Italiani di Dalmazia: 1919-1924" di Luciano Monzali

- ^ "Il primo esodo dei Dalmati: 1870, 1880 e 1920 - Secolo Trentino". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Map (JPG format)". Ibiblio.org. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Annessioni italiane (1941)" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Thammy Evans & Rudolf Abraham (2013). Istria. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 11. ISBN 9781841624457.

- ^ James M. Markham (6 June 1987). "Election Opens Old Wounds in Trieste". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "SAS Output". dzs.hr. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Central Bureau of Statistics". Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Central Bureau of Statistics". Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Government use of the Italian language in Rijeka

- ^ "SAS Output". dzs.hr. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Comunità Nazionale Italiana, Unione Italiana". www.unione-italiana.hr. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "LA LINGUA ITALIANA E LE SCUOLE ITALIANE NEL TERRITORIO ISTRIANO" (in Italian). p. 161. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Byron: the first language school in Istria". www.byronlang.net. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ Reazioni scandalizzate per il rifiuto governativo croato ad autorizzare un asilo italiano a Zara

- ^ Zara: ok all'apertura dell'asilo italiano

- ^ Aperto “Pinocchio”, primo asilo italiano nella città di Zara

- ^ "L'italiano con modello C a breve in una scuola di Zara". Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.