This is a benchmark that tries to compare the performance of Elm, React, Ember, and Angular in a fair way. I highly recommend reading the full analysis, but the very short summary is that Elm is the fastest.

I collected graphs for a bunch of different browsers here, so you can see how the numbers vary across different JS virtual machines.

That is just on my computer though, so I wanted everyone to be able to run this in their own browsers and see the results for themselves. You can do that here.

My goal with these benchmarks was to compare renderer performance in a realistic scenario. This means rendering each frame in full, exactly like you would if a real user was interacting with the TodoMVC app. I acheived this by making two major rules:

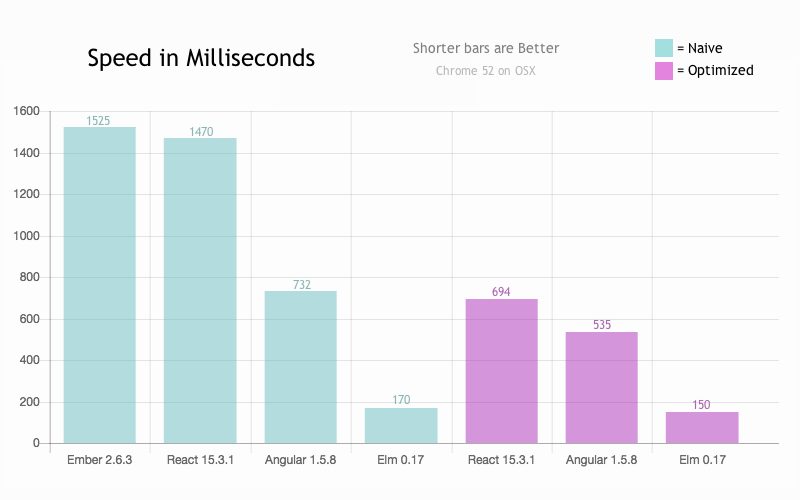

To run these benchmarks, I need to simulate user input. The naive way to do that is to generate a ton of events on a for loop all at once. That results in the following graph:

Holy smokes, it looks like Elm is 3x to 8x faster than some of the competitors! But everyone is going way faster in the first place too... What is going on here?

If you run this benchmark for yourself, you will see that each implementation displays exactly four frames: no entries, one-hundred entries, one-hundred complete entries, and then no entries again. By generating all the events in a single for loop, we ensure that they all end up in a big contiguous block on JavaScript’s event queue. So when Elm or React finally gets a chance to run, they just churn through all these events. JavaScript is single threaded, so while this work is happening, we are unable to refresh the view for the user. So the browser is just not painting any frames at all. Instead of painting 100 frames, we paint just one!

So this is bad for an obvious reason: it is impossible to make the event queue look like this in practice. When a user creates an event, Elm or React or Angular will always get woken up before another user event comes in. A user simply cannot generate a contiguous block of events on the event queue.

So this is not measuring reality, but it still has some interesting information. This graph measures the core virtual DOM implementation more directly. This approach seems to strip out all the time spent by the browser turning DOM into pixels. Turns out, this accounts for an overwhelming majority of the time in the fair graphs. If these numbers are even vaguely decent estimates for time spent in the virtual DOM implementation, Elm is doing really well!

Note: In the fair approach, we generate a step for every event, like this, and measure each step individually. In the batched approach, there are only three steps that generate all the events at once, like this.

Also, I left Angular 2 out of this graph because they are doing some trick I do not fully understand. Instead of showing 4 frames, they only show one: no entries. I suspect they are using

setTimeoutor something to delay rendering, and in this particular case, that can mean you only diff the first state against the last state. It just so happens that those are empty todo lists, so you essentially build nothing and diff nothing. I would need to know a lot more about their implementation to sort out exactly what is going on there.

Browsers typically repaint their content at most 60 times per second. So if you are writing JavaScript that has it changing the content 120 times per second, half of that work is wasted. Furthermore, you want your repaints to be at very even intervals so that the 60 repaints align with the 60hz of most monitors. To get the smoothest animations possible, you need to sync up with this.

So requestAnimationFrame was introduced. It lets you say “here is a function that modifies the DOM, but I want the browser to make the changes whenever it thinks it is a good idea.” That means the repaints get smoothed out to 60 FPS no matter how crazy your JS happens to be.

Say you get events coming in extremely quickly, and you get four events within a single frame. A naive use of requestAnimationFrame would just schedule them all to happen in sequence. So you would build all four virtual DOMs, diff them against each other in sequence, and show the final result to the user. We can do better though! We can just skip three of those frames entirely. Instead diff the current virtual DOM against the latest virtual DOM. The end result is exactly the same (the user sees the final result) but we skipped 75% of the work!

Elm does this optimization by default. If you are using Elm, you already have this enabled and your animations are just way smoother out of the box. None of the other frameworks (Angular, Ember, or React) do this by default, and it is not their fault. If you are writing code in JavaScript (or TypeScript) this optimization is not safe at all. This optimization is all about rescheduling and skipping work, and in JavaScript, that work may have some observable effect on the rest of your program. Say you mutate your some state from the view. Simple. Common. There are two ways this can go wrong:

-

Using

requestAnimationFramemeans this mutation happens later than you expected. In the meantime, you may need to do other work that depends on that mutation having already happened. So if another event comes in beforerequestAnimationFrameyou now have a very sneaky timing bug. -

If you have

requestAnimationFrameskip frames, the mutation may just never happen. Your application state just does not get updated correctly. This kind of bug would be truly awful to hunt down. You need a specific sequence of events to come in, one of them causing a mutation. You need them to come in so fast that they all happen within a single frame. You also need them to come in a specific order such that the event that causes mutation is one of the ones that gets dropped. This could be the definition of a Heisenbug and I do not think I could create a more difficult bug on purpose.

In both cases, the fundamental problem is that mutation is possible in your view code in JavaScript or TypeScript. A programmer can mutate something, and nothing that the React or Angular team does will change this fact. Given that, I personally think it would be crazy for them to have this kind of optimization turned on by default. In that world, using React or Angular would almost guarantee that you see these bugs in practice.

To bring it back to these benchmarks, the simulated user input comes in really fast, so if I let Elm use requestAnimationFrame like it normally would, it would end up skipping tons of frames. That would look good, but if those events were created by a real human being, I doubt any of them would happen within a single frame. So in the more realistic scenario, this optimization is not going to have an impact on events that are as slow as human beings. So yes, it is really nice that Elm has this by default, and it definitely makes sense to take that into account when deciding if you want to use Elm, but it would not be fair for this benchmark.

If you want to fork this repo and try things out, the easiest way is probably to just switch to the gh-pages branch where the necessary assets are already checked in. Otherwise, you need to run something like this:

cd src

elm-make Picker.elm --output=picker.jsAnd then navigate into implementations/*/readme.md and follow the build instructions for the various projects.